Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Made a Lawman “Wild” on the Frontier?

- #10 Pat Garrett

- #9 Bill Tilghman

- #8 William “Dave” Allison

- #7 John Hicks Adams

- #6 John Barclay Armstrong

- #5 Harry Wheeler

- #4 Henry Andrew “Heck” Thomas

- #3 John Reynolds Hughes

- #2 Seth Bullock

- #1 Bat Masterson

- Why These Lawmen Still Fascinate Us

- Experiences: What It Feels Like to Chase the Old West Today (500+ Words)

- Conclusion

The Old West didn’t come with guardrails. It came with dust, bad lighting, worse communication, and a justice system

that often arrived on horsebacklate, tired, and deeply unimpressed. In that world, “lawman” wasn’t a neat job title.

It was a survival strategy with a badge attached.

When we picture Western lawmen, we tend to imagine clean moral lines: white hat, black hat, dramatic music, roll credits.

Reality was messier. Sheriffs, marshals, and rangers worked in places where jurisdictions overlapped, paperwork was optional,

and a “warrant” might be a folded note that said “Please stop that guy.” Some lawmen were careful professionals. Others were

human thunderclapseffective, controversial, and occasionally one poor decision away from becoming the next wanted poster.

What Made a Lawman “Wild” on the Frontier?

- They chased dangerous people when backup was a rumor and help was a two-day ride away.

- They operated in gray zonesbetween law, politics, local power brokers, and personal grudges.

- They became legends while still alive, which is always a risky thing for anyone holding a gun.

- They left storiessome documented, some embellished, and some passed down like a campfire spark.

Below are ten lawmen whose careers blended courage, calculation, and the kind of high-stakes chaos that makes modern job

interviews feel like a spa day.

#10 Pat Garrett

Pat Garrett is forever tied to one name: Billy the Kid. In a frontier culture that turned outlaws into folk heroes, Garrett

found himself cast as the man who ended the storywhether the audience liked it or not.

After becoming sheriff in Lincoln County, New Mexico, Garrett took on the job of tracking down the Kid, who had already become

a headline magnet. Garrett captured him once, watched him escape, and then hunted him down again. The final confrontation at

Fort Sumner has been argued over ever since: Was it an unavoidable split-second shooting, or an ambush that felt like betrayal?

The West, never shy about an argument, kept debating long after the smoke cleared.

Wild factor: Garrett’s “victory” came with a public relations hangover. In the Old West, even doing your job could make you

unpopularespecially when your job required ending somebody else’s legend.

#9 Bill Tilghman

Bill Tilghman had the kind of career that reads like a long-running TV series: new town, new crisis, same calm professional

walking into danger like it’s a scheduled appointment.

He built a reputation as a methodical manhuntersomeone who didn’t rush to violence, but also didn’t hesitate when the moment

arrived. Tilghman is strongly associated with the “Three Guardsmen” (alongside Heck Thomas and Chris Madsen), deputy U.S. marshals

known for applying relentless pressure to outlaw gangs in Oklahoma and Indian Territory.

Wild factor: Tilghman’s brand of wild was endurance. He kept goingyear after yearthrough outlaw eras, boomtown politics,

and the exhausting reality of chasing people who truly did not want to be found.

#8 William “Dave” Allison

Dave Allison’s story has a sharp edge because it stretches into a later Westwhen the frontier was “closing” on paper, but

the danger hadn’t read the memo.

Known for becoming Texas’s youngest sheriff (elected in 1888 in Midland County at age 27), Allison’s career moved through roles

that put him in the middle of high-risk work: law enforcement, ranger service, and later investigations tied to cattle theft

and frontier-era organized crime.

His end is as grim as anything in a Western: shot down in Seminole, Texas, in 1923 while working a case and preparing to testify.

It’s a reminder that “wild” wasn’t just about shootoutsit was also about the slow, dangerous grind of taking on people with money,

leverage, and guns.

#7 John Hicks Adams

John Hicks Adams brought law enforcement muscle to a part of the West many people forget was turbulent: Civil War–era California.

While the major battlefields were far away, the politicsand violencestill showed up on the Pacific frontier.

As sheriff in Santa Clara County, Adams pursued armed groups and partisan-style criminals, forming posses and pushing into dangerous

territory to break up gangs that mixed ideology with outright robbery. In a period when loyalties were divided and rumors traveled fast,

the sheriff’s job wasn’t just enforcementit was stabilizing a community that could tilt toward chaos.

Wild factor: Adams operated in a pressure cooker where crime, wartime politics, and local allegiances collided. Think “lawman,”

but with extra paranoia and fewer reliable witnesses.

#6 John Barclay Armstrong

John Barclay Armstrong earned one of the more intimidating nicknames in Texas Ranger history: “McNelly’s Bulldog,” tied to his service

under Captain Leander McNelly in the Rangers’ Special Force.

Armstrong is often remembered for capturing the notorious gunman John Wesley Hardinan arrest that required nerve, timing, and the kind

of calm that only comes from having already survived too many bad days. Accounts describe a tense confrontation during transport, followed

by Armstrong successfully disarming and delivering Hardin to face justice.

Wild factor: Armstrong’s wildness was competence under pressure. He wasn’t chasing fame; he was chasing outcomesand he had the scars

(literal and professional) to prove it.

#5 Harry Wheeler

If you like your Old West stories with a “late-era” twistwhen automobiles existed but trouble still preferred revolversHarry Wheeler

is your guy.

As an Arizona Ranger, Wheeler was involved in the Shootout in Benson (1907), a gunfight that became one of the last famous “classic”

Western-style confrontations. Wheeler and J.A. Tracy exchanged gunfire at close range; both were wounded, and Tracy later died.

Later, as Cochise County sheriff, Wheeler found himself in the Gleeson gunfight (1917), an ambush-style firefight tied to smuggling and

borderland crime. Even as the frontier era faded, the risks remained very realand Wheeler kept stepping into them.

Wild factor: Wheeler’s career shows how long “Old West” danger lingered. The calendar moved forward; the bullets didn’t care.

#4 Henry Andrew “Heck” Thomas

Heck Thomas was a deputy U.S. marshal known for being relentlessless “quick draw,” more “eventually draw, after I’ve tracked you across

half a territory and you’re too tired to argue.”

As part of the Three Guardsmen, Thomas helped wage sustained pressure against outlaw gangs that exploited the maze of jurisdictions in

Oklahoma and Indian Territory. Those pursuits weren’t glamorous: long rides, thin leads, informants who lied, and criminals who were

heavily armed and highly motivated.

Thomas was associated with major clashes like the Battle of Ingalls (1893), a vivid example of how dangerous it was to confront organized

outlaw groups who could shoot well, disappear quickly, and sometimes intimidate entire communities into silence.

Wild factor: Thomas’s wildness was persistence with teeth. He didn’t just face dangerhe followed it until it ran out of road.

#3 John Reynolds Hughes

John Reynolds Hughes didn’t start out aiming for legend status. He built it the hard waythrough years of Texas Ranger service along the

border, where problems were complicated, fast-moving, and often international.

Hughes rose through the Rangers and became known for his ability to pursue suspects across harsh terrain and tangled politics. He worked

in an era when border violence could involve bandits, smugglers, and cross-border tensions that demanded both toughness and diplomacy.

Wild factor: Hughes represents the “working wild”not a single shootout, but a career spent hunting dangerous men while balancing law,

community pressure, and a border that didn’t behave like a neat line on a map.

#2 Seth Bullock

Seth Bullock is inseparable from Deadwood, South Dakotaan infamous boomtown where gold brought money, and money brought trouble like a

dinner bell.

Bullock became Deadwood’s first sheriff when residents demanded a steadier hand. His approach combined presence, reputation, and a willingness

to confront violence before it became routine. Later, his relationship with Theodore Roosevelt became part of Western political folklore,

and Bullock went on to serve as U.S. marshal for South Dakota.

Wild factor: Bullock’s version of wild was civilizing chaos while standing in the middle of it. Deadwood didn’t “calm down” because it felt

like itDeadwood calmed down because men like Bullock made disorder expensive.

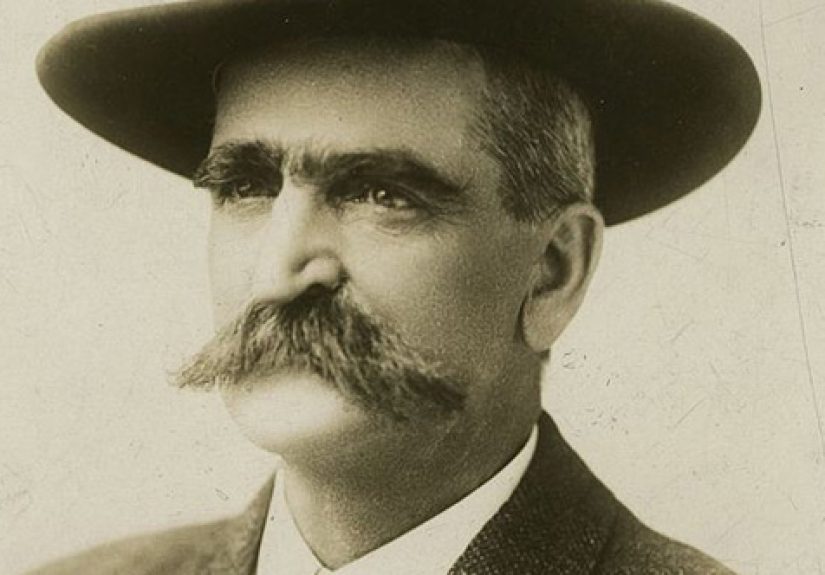

#1 Bat Masterson

Bat Masterson is proof that the Old West could produce a man who was simultaneously a lawman, a gambler, and (eventually) a newspaper

columnistbecause nothing says “well-rounded professional” like gunfights and journalism.

In Dodge City, Masterson moved through the classic Western roles: buffalo hunter, scout, lawman, and a figure who navigated the messy overlap

of vice economies and civic order. He wasn’t just enforcing rules; he was enforcing stability in a town where stability wasn’t anyone’s natural

setting.

Later, Masterson reinvented himself in New York as a sportswriter, proving that you can leave the West, but the West will happily follow you

into your byline.

Wild factor: Masterson’s wildness was adaptability. He survived the frontier and then survived fametwo challenges that have ended many careers,

often in that order.

Why These Lawmen Still Fascinate Us

The “wild lawman” archetype endures because it sits on a tension Americans still recognize: we want order, but we’re suspicious of power; we

admire courage, but we worry about recklessness; we love a hero, but we also love arguing about whether he really was one.

These men worked in a world where the gap between “legal” and “effective” could be dangerously wide. Some were careful professionals forced

into violent decisions. Others were undeniably rough characters who fit their era a little too well. Their storiespart record, part myth

are a reminder that frontier justice wasn’t a simple morality play. It was improvisation with consequences.

Experiences: What It Feels Like to Chase the Old West Today (500+ Words)

Reading about Old West lawmen is one experience; standing where their stories happened is another. If you’ve ever walked down a restored main

street in a Western townreal or reconstructedyou’ve probably felt that strange double sensation: everything looks smaller than the movies,

and somehow more intense. The alleys are narrow. The distances between buildings are short. You realize that many “legendary showdowns” took

place within a space where you could toss a baseball. That closeness makes the risk feel immediate. A gunfight wasn’t a cinematic balletit was

a blink-and-you’re-done catastrophe.

Visiting places linked to these lawmen can be surprisingly emotional, even if you’re not the “get misty over history” type. In Deadwood, for

example, the story isn’t just about Seth Bullock and the badgeit’s about the collision of ambition, fear, and opportunity that turned a camp

into a town. You can almost hear the background noise in your imagination: boots on boardwalks, arguments spilling out of saloons, someone

laughing too loudly because they’re trying to prove they’re not scared. It becomes easier to understand why a strong-willed sheriff mattered.

Civilization, out there, wasn’t automatic. It was negotiated, enforced, and sometimes dragged into place.

There’s also the “paper trail experience”the kind you get when you dive into old newspaper archives, court records, or museum exhibits. It’s a

humbling way to meet the past, because it strips away the heroic framing and replaces it with details: dates, injuries, witnesses who disagree,

and officials arguing about budgets while violence escalates outside. You start to notice how often a lawman’s job was less about a dramatic

duel and more about logistics: assembling a posse, finding fresh horses, convincing someone to talk, or tracking a suspect who keeps slipping

across jurisdictions.

Modern Western events and reenactments add another layerhalf education, half community theater, and often full of people who really care about

getting the hats right. Watching a staged shootout can be fun, but the most memorable moments are usually the quiet ones afterward: a volunteer

explaining how a town marshal was elected, or a guide pointing out that the “famous street” was also where families bought groceries. Those

small, domestic details make the lawmen feel more human. Pat Garrett wasn’t born into a legend; he became one through choices that had costs.

Bill Tilghman’s reputation wasn’t a slogan; it was the accumulation of countless confrontations where “doing nothing” could be fatal.

Finally, there’s the personal reflection many readers have after spending time with these stories: the Old West was chaotic, but it was also

structured by people who triedsometimes wisely, sometimes brutallyto impose rules. That doesn’t mean we have to romanticize their methods.

It means we can appreciate the complexity: courage tangled with ego, public duty mixed with private motives, and justice pursued in a world

where the line between lawman and outlaw could look uncomfortably thin at sunset.

Conclusion

The wild lawmen of the Old West weren’t superheroes. They were men operating in environments where a single mistake could end a careeror a life.

Their stories survive because they reveal something timeless: when systems are fragile, individuals matter more, and the price of order can be

startlingly high.