Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Accessible Website” Actually Means (in Human Terms)

- What Great Accessible Sites Have in Common

- 14 Accessible Website Examples (and What to Steal for Yours)

- 1) USA.gov

- 2) Section508.gov

- 3) U.S. Web Design System (USWDS)

- 4) NASA.gov

- 5) CDC.gov

- 6) IRS.gov

- 7) HHS.gov (Digital Accessibility Statement)

- 8) NIH.gov

- 9) National Park Service (NPS.gov)

- 10) Library of Congress (LOC.gov)

- 11) Medicare.gov

- 12) U.S. Department of State (State.gov)

- 13) American Foundation for the Blind (AFB.org)

- 14) Target.com

- Turn Inspiration Into Action: A Fast Accessibility Upgrade Plan

- Common Accessibility Mistakes (That Are Weirdly Easy to Avoid)

- Experiences That Make Accessibility “Click” (500+ Words of Real-World Lessons)

- SEO Tags

Website accessibility isn’t a “nice-to-have” that you sprinkle on after launch like powdered sugar. It’s the batter.

It’s what lets real peopleusing screen readers, keyboard-only navigation, captions, zoom, voice control, and other assistive techactually use your site.

And yes, it also tends to make your site easier for everyone (including the impatient folks on a cracked phone screen in bright sunlight… so, all of us).

The good news: you don’t have to reinvent accessibility from scratch. Plenty of organizations have already put in the work,

published accessibility commitments, and built patterns you can borrow. Below are 14 accessibility-forward websites (mostly U.S.-based)

plus the specific ideas worth “respectfully remixing” for your own site.

What “Accessible Website” Actually Means (in Human Terms)

An accessible website is one that people with disabilities can perceive, operate, understand, and use reliablyregardless of device,

browser, or assistive technology. In practice, that often means designing and building to recognized standards like WCAG

(Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) and, for many U.S. organizations, aligning with legal requirements such as Section 508 (federal ICT) and the ADA.

The “POUR” shortcut

- Perceivable: Text alternatives for images, captions for videos, clear contrast, content that works when zoomed.

- Operable: Fully usable with a keyboard; visible focus states; no traps; reasonable time limits.

- Understandable: Clear labels, consistent navigation, helpful error messages, plain language where possible.

- Robust: Clean semantic HTML and ARIA where needed so assistive tech can interpret it correctly.

What Great Accessible Sites Have in Common

Before we get to the examples, here are the repeatable patterns you’ll see again and again:

1) They treat keyboard users like first-class citizens

If someone can’t use a mouse, your site should still be fully functional. That includes logical tab order, visible focus indicators,

and no “mystery meat” buttons that only work on hover.

2) They build with real structure, not vibes

Headings are in order, buttons are actual buttons, forms have labels, and navigation landmarks exist. Screen readers love structure.

(So do search engines. Everybody wins.)

3) They offer multiple ways to access content

Alternative formats (HTML versions of documents, accessible PDFs, large print, captions, transcripts) show up a lotespecially on government sites.

4) They make it easy to report issues

Accessibility isn’t a one-time checkbox. Strong sites publish contact options, describe standards used, and acknowledge that improvements are ongoing.

14 Accessible Website Examples (and What to Steal for Yours)

These examples aren’t presented as “perfect forever.” Accessibility is an ongoing practicesites evolve, content changes, and new issues can appear.

What matters is that these organizations show clear commitments, publish accessibility information, and provide patterns you can apply immediately.

1) USA.gov

USA.gov is a masterclass in plain-language information architecturepaired with a public accessibility policy. It’s built to help people find critical

services without needing a scavenger-hunt trophy.

- Steal this: Clear, predictable navigation and straightforward page layouts.

- Steal this: A public accessibility policy that sets expectations and defines standards.

- Steal this: Content written like a human helping a human (not like a robot defending a dissertation).

2) Section508.gov

If accessibility standards were a “home base” for U.S. federal digital work, this would be it. Section508.gov explains how conformance applies and

offers practical guidance for building and managing accessible ICT.

- Steal this: Plain, scannable explanations of standards and responsibilities.

- Steal this: A dedicated “how we handle accessibility” hub instead of burying it in a footer link graveyard.

- Steal this: Clear terminology that reduces confusion across designers, devs, and content teams.

3) U.S. Web Design System (USWDS)

USWDS is a design system used across government sites, and it explicitly discusses accessibility goals and practices. The big idea: bake accessible

components into your system so every new page doesn’t become a fresh accessibility gamble.

- Steal this: A reusable component library with accessibility as a baseline, not an add-on.

- Steal this: Patterns for forms, alerts, navigation, and tables that encourage consistent semantics.

- Steal this: Documentation that helps teams implement correctly (because “just make it accessible” is not a spec).

4) NASA.gov

NASA publishes an accessibility commitment that references Section 508 and WCAG conformance. Beyond the statement, NASA’s web presence has to serve a

massive, diverse audiencestudents, researchers, journalists, and the general public.

- Steal this: A clear accessibility commitment and standards alignment.

- Steal this: Content designed for scanning: headings, subheads, and structured sections.

- Steal this: Strong media discipline (images, video, and interactive content that are thoughtfully presented).

5) CDC.gov

The CDC’s site provides a straightforward way to report accessibility problems and discusses accessibility obligations under Section 508.

For public-health information, accessibility isn’t just usabilityit’s equity.

- Steal this: A visible “report an accessibility problem” pathway.

- Steal this: Clear, task-based information design (users can find what they need without decoding jargon).

- Steal this: A culture of “feedback welcomed,” which is essential for continuous improvement.

6) IRS.gov

The IRS provides accessible tax materials in multiple formats (including accessible PDFs, large print, and Braille) and highlights accessibility-friendly

resources like ASL videos. It’s a strong model for “content accessibility,” not just interface accessibility.

- Steal this: Alternative formats for high-stakes content (forms, instructions, publications).

- Steal this: Clear categorization so users can quickly find accessible versions.

- Steal this: Accessibility as a service: not “good luck,” but “here are the options.”

7) HHS.gov (Digital Accessibility Statement)

HHS publishes a digital accessibility statement that sets a baseline (at minimum) for standards and best practices across a large ecosystem.

Big organizations benefit from central guidance that keeps accessibility consistent across teams and vendors.

- Steal this: A centralized accessibility statement that applies across a family of sites.

- Steal this: Clear governance languagewho owns accessibility, how it’s maintained, and what standards apply.

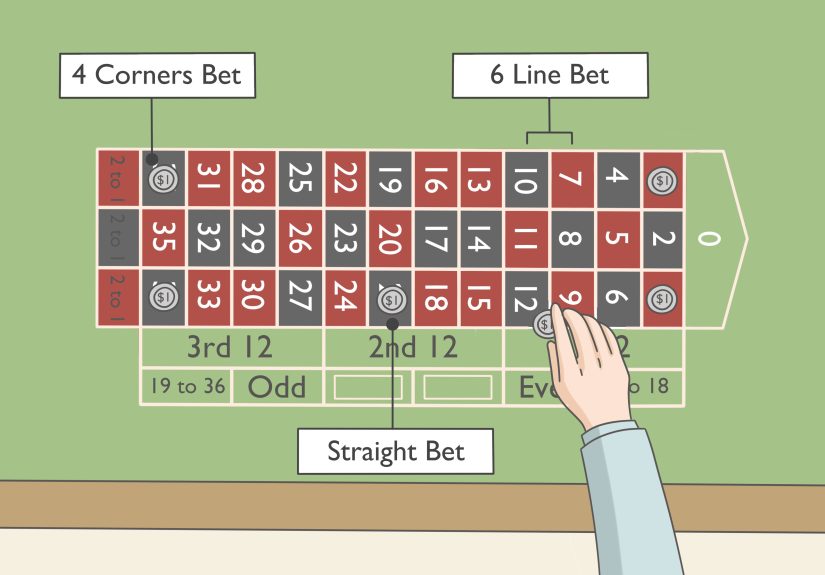

- Steal this: A “minimum standard” baseline that prevents teams from drifting into accessibility roulette.

8) NIH.gov

NIH states its effort to ensure web information is accessible and provides a way to contact them if a user encounters barriers.

That combinationcommitment plus a support pathis a practical, user-first approach.

- Steal this: Clear contact options when users hit an accessibility barrier.

- Steal this: Simple messaging that invites specific feedback (what page, what problem, what tool).

- Steal this: Accessibility positioned as part of serving the public, not as a compliance chore.

9) National Park Service (NPS.gov)

NPS describes its commitment to accessible information and communication technologies under Section 508. With content ranging from trip planning to

education, NPS demonstrates the value of consistent accessibility expectations across a huge content library.

- Steal this: Organization-wide commitment language that applies broadly, not just to a single page.

- Steal this: Consistent content structure across many sections and topics.

- Steal this: Accessibility framed as ensuring equal access to services and information.

10) Library of Congress (LOC.gov)

The Library of Congress discusses web accessibility and acknowledges that legacy pages may be in progressan honest (and realistic) approach for large,

long-running sites. Transparency builds trust.

- Steal this: A dedicated web accessibility page that sets expectations and acknowledges ongoing upgrades.

- Steal this: Structured navigation through massive collectionsorganized information is accessible information.

- Steal this: Commitment language that treats accessibility as continuous work.

11) Medicare.gov

Medicare provides an accessibility and nondiscrimination notice describing auxiliary aids and services and accessible communications options.

For many users, accessibility isn’t optionalit’s the difference between “I can use this” and “I can’t.”

- Steal this: Clear explanation of accessible communication options and how to request them.

- Steal this: User-first language that anticipates real-world barriers (and how support works).

- Steal this: Accessibility information that’s easy to find and written plainly.

12) U.S. Department of State (State.gov)

State.gov publishes a Section 508 accessibility statement. For any organization, publishing an accessibility statement is a strong signal: it tells users,

teams, and vendors what “done” looks like (and how to report what isn’t).

- Steal this: An accessibility statement that clarifies standards and points to support options.

- Steal this: Policy-level clarity that can be reused across sub-sites.

- Steal this: A public commitment that encourages accountability.

13) American Foundation for the Blind (AFB.org)

AFB is an advocacy organization serving people who are blind or have low vision, and it publishes an accessibility policy referencing WCAG. It also provides

practical resources on topics like keyboard accessibility, forms, and image descriptions.

- Steal this: A clear accessibility policy and a “we practice what we preach” approach.

- Steal this: Strong emphasis on real user needs (screen reader patterns, clear descriptions, keyboard support).

- Steal this: Educational content that helps teams improve, not just comply.

14) Target.com

Target publishes an accessibility commitment and support paths related to digital accessibility. Retail UX is complexsearch, filters, carts, checkout

and accessibility has to survive all that complexity. Target’s public commitment is a strong example for e-commerce brands.

- Steal this: A clear accessibility commitment for online shopping experiences.

- Steal this: Support options for accessibility questions or barriers.

- Steal this: The mindset that accessibility applies to the whole journey, not just the homepage.

Turn Inspiration Into Action: A Fast Accessibility Upgrade Plan

Step 1: Run a “no-mouse” test (10 minutes)

- Can you reach every link, button, input, menu, and modal using Tab, Shift+Tab, Enter, and arrow keys?

- Is there a visible focus indicator so you always know where you are?

- Can you escape popups and menus without getting trapped?

Step 2: Check your structure (10 minutes)

- Is there exactly one logical H1 and are headings nested in a sensible order?

- Do form inputs have programmatic labels (not just placeholder text)?

- Do interactive elements use semantic HTML (real

<button>, real<a>)?

Step 3: Fix the “big three” content issues (30–60 minutes)

- Alt text: Add meaningful alt text to informative images; mark decorative images as decorative.

- Contrast: Ensure text and essential UI elements meet contrast expectations (especially for buttons and form states).

- Media: Add captions for video; provide transcripts for audio when possible.

Step 4: Publish an accessibility statement (and mean it)

Many of the sites above publish accessibility statements or policies. Yours doesn’t have to be fancy, but it should be real:

say what standard you’re aiming for (e.g., WCAG level), note any known limitations, and provide a clear way for users to report problems.

Common Accessibility Mistakes (That Are Weirdly Easy to Avoid)

- Hover-only interactions: If it only appears on hover, keyboard and touch users may never see it.

- Placeholder-as-label: Placeholders disappear; labels don’t. Use labels.

- Focus that vanishes: Removing outlines without replacing them is the digital version of turning off the lights in a stairwell.

- “Click here” links: Screen reader users often navigate by links. Make link text descriptive.

- PDF-only important info: If you must use PDFs, make them accessible and consider offering HTML alternatives too.

Experiences That Make Accessibility “Click” (500+ Words of Real-World Lessons)

Most teams don’t ignore accessibility because they’re cruel villains twirling mustaches in a dark UX lair. Usually, they ignore it because they’re busy,

they’re shipping, and accessibility feels like “extra.” Then something happens that turns accessibility from a theory into a very real, very human moment.

One common experience is the keyboard-only reality check. A developer or designer tries navigating their own site without a mouse and suddenly

realizes the tab order jumps like a caffeinated squirrel. The focus indicator disappears. A dropdown opens… and then refuses to close. That’s often the first

“aha”: the site isn’t just inconvenientit’s unusable for someone who relies on keyboard navigation. The fix is rarely glamorous, but it’s powerful:

restore visible focus styles, make tab order logical, ensure every interactive element is reachable, and confirm you can escape menus and modals.

Another big moment comes from screen reader testing. You don’t need to become a full-time assistive-technology expert to learn something valuable

in 15 minutes. Teams will hear a screen reader announce “button, button, button” because icon-only controls weren’t labeled. Or a form field gets read as “edit text”

with no context because the label wasn’t properly associated. Suddenly, “semantic HTML” stops sounding like a fancy phrase and starts sounding like a lifeline.

The lesson: structure isn’t optional decoration; it’s the interface.

Content teams often experience accessibility through alt text and headings. At first, alt text feels like homework. Then someone points out:

alt text is how a blind user participates in the same story sighted users get instantly. Teams learn to write alt text that’s specific, concise, and useful.

Not “image123.jpg,” not “a photo,” and definitely not “graphic.” Instead: what matters here? If the image is decorative, mark it as decorative and move on.

The best content teams get faster at thisand their pages become clearer for everyone.

A particularly humbling (and common) experience is the color and contrast surprise. A brand palette looks gorgeous in a mockup, then fails in the real

world: dim screens, sunlight, low vision, or older monitors. Teams discover that accessible contrast doesn’t kill creativityit forces clarity.

They start designing buttons that look like buttons, links that look like links, and error states that don’t rely on color alone. Suddenly the UI is more confident,

not less stylish.

The most mature teams eventually run into the truth that accessibility is a process, not a finish line. New pages get added, marketing campaigns launch,

third-party widgets show up, and accessibility can regress unless it’s part of the workflow. That’s why so many exemplary sites publish statements, feedback channels,

and standards commitments: it creates accountability. The practical takeaway is simple: add accessibility checks to design reviews, code reviews, and content QA.

If you can ship bugs, you can ship accessibility improvementsjust make it part of what “done” means.

Finally, teams often discover the most underrated benefit: accessibility improves overall UX. Clear navigation helps everyone. Descriptive links help everyone.

Captions help people in noisy spaces. Better error messages reduce support tickets. Keyboard support benefits power users. In other words, accessibility isn’t a detour

it’s the main road to a site that works.