Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Did So Many Kings Take the Throne as Children?

- The 14 Youngest Kings In History

- John I of France (“John the Posthumous”) King from birth (1316)

- Alfonso XIII of Spain Proclaimed king immediately at birth (1886)

- Sobhuza II of Swaziland (Eswatini) Chosen king at about 4 months (1899)

- Fuad II of Egypt King at about 6 months (1952)

- Henry VI of England King at 9 months (1422)

- James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) Crowned at 13 months (1567)

- Faisal II of Iraq King at 4 years old (1939)

- Louis XIV of France King at 4 years, 8 months (1643)

- Ptolemy V Epiphanes of Egypt King at 5 years old (204 BCE)

- Michael I of Romania King at 5 years old (1927)

- Pepi II of ancient Egypt Traditionally placed around age 6 at accession (c. 23rd century BCE)

- Simeon II of Bulgaria King at 6 years old (1943)

- Josiah of Judah King at 8 years old (7th century BCE)

- Tutankhamun (“King Tut”) Became king around age 9 (c. 14th century BCE)

- What These Child Kings Reveal About Power

- How Historians Talk About “Youngest Kings” Without Getting Tripped Up

- Reader Experiences: What It Feels Like to Step Into the World of the Youngest Kings

- Conclusion

History is full of dramatic coronations: glittering crowns, cheering crowds, and the occasional horse that clearly did not consent to being part of the ceremony.

But some of the most jaw-dropping “royal beginnings” didn’t start with a triumphant adult stepping forwardthey started with a baby.

In some kingdoms, the crown didn’t wait for you to learn your ABCs. It barely waited for you to learn how to hold your own head up.

This article explores 14 of the youngest kings in historyfrom newborn monarchs to “boy kings” who inherited thrones before they could possibly run a government.

Along the way, we’ll unpack why child monarchs happened so often, how royal regencies actually worked, and what these early reigns reveal about power, politics, and the surprisingly fragile idea of legitimacy.

Why Did So Many Kings Take the Throne as Children?

If you’re wondering, “How did anyone think this was a good idea?”you’re asking the right question. Most societies didn’t choose child kings because they

believed toddlers were gifted policymakers. Child kings happened because of succession rules, dynastic survival, and the blunt reality that

in many eras, adults died young and often.

1) Succession laws didn’t care about age

In many monarchies, the crown passed automatically to the legitimate heirno auditions, no resumes, no “we’ll circle back after kindergarten.”

If the rightful heir was three months old, then three months old it was. The alternativeskipping the heircould trigger civil war, rival claimants,

or a power grab dressed up as “for the good of the realm.”

2) Regencies were the real engine of government

When a king was too young to rule, adults governed in his name. This periodcalled a regencycould stabilize a kingdom… or turn it into

a high-stakes chess match between relatives, nobles, generals, and religious leaders. The crown remained the child’s; the power often didn’t.

3) Child kings were politically useful

A child king could be a compromise candidate. He was “legitimate” enough to unite factions, and young enough that ambitious adults assumed they could

steer the ship. Sometimes that worked. Sometimes it ended with a regent steering the ship directly into the palace treasury.

The 14 Youngest Kings In History

Ages can be surprisingly tricky in ancient sources, and “becoming king” can mean different things (proclaimed, crowned, enthroned, or recognized by rivals).

So think of this as a well-sourced lineup of very young monarchsplus the political realities that shaped their reigns.

-

John I of France (“John the Posthumous”) King from birth (1316)

John I is the ultimate example of a crown that didn’t wait. Born after his father’s death, he was recognized as king of France immediatelythen died just a

few days later. His reign was so short it’s practically a historical footnote, but the stakes were enormous: France had to decide whether a posthumous infant

“counted” as king (it did), and who would follow next. Even a five-day reign could reshape succession and spark rumors for years. -

Alfonso XIII of Spain Proclaimed king immediately at birth (1886)

Alfonso XIII was born into the throne as the posthumous son of Alfonso XII. He was proclaimed king right away, with his mother serving as regent until he came

of age. His story highlights a recurring theme: an infant king could keep a dynasty legally intact, while grown-ups handled the politics. But it also shows how

“legitimacy” doesn’t automatically equal “stability.” Spain’s political tensions didn’t pause just because the king was a newborn. -

Sobhuza II of Swaziland (Eswatini) Chosen king at about 4 months (1899)

Sobhuza II is famous for one of the longest reigns in recorded historybut it started when he was still an infant. Chosen as king while only a few months old,

he ruled under a long regency before assuming full authority later. His early accession shows how monarchies can separate the symbol of rule

(the child king) from the mechanics of rule (the regent council), sometimes for decades. -

Fuad II of Egypt King at about 6 months (1952)

Fuad II became king as an infant during Egypt’s revolutionary upheaval. His reign was brief and largely symbolicmore like a legal placeholder while the old

system collapsed and a new one formed. If you want a modern reminder that crowns can become political props, this is it: sometimes a baby king isn’t installed

because anyone expects him to rule, but because leaders hope the monarchy can be preserved long enough to negotiate an exit ramp. -

Henry VI of England King at 9 months (1422)

Henry VI inherited the English throne as a baby and was also proclaimed king of France shortly afterward (in the context of the Hundred Years’ War).

Since babies are famously bad at cabinet meetings, England depended on powerful adults to governcreating openings for factional rivalry that would later feed

into the Wars of the Roses. Henry’s life is a sobering case study in what happens when a child monarch grows up amid conflict: the crown can become less a tool

of leadership and more a magnet for competing interests. -

James VI of Scotland (later James I of England) Crowned at 13 months (1567)

James became king of Scotland as an infant after his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, abdicated. He was crowned at thirteen months olda detail so striking that

he later described himself as a “cradle king.” For years, regents governed as rival religious and political forces pulled Scotland in different directions.

His reign shows how a child king could be both a unifying symbol and a vulnerable prize, especially in a country wrestling with major religious change. -

Faisal II of Iraq King at 4 years old (1939)

Faisal II became king after his father’s death when he was only four. A regent ruled during his minority, a common solution that looks neat on paperuntil you

remember that regents have interests, allies, enemies, and ambitions. Faisal’s story also highlights a recurring modern pattern: young monarchs in politically

turbulent times often inherit not just a crown, but a storm system already forming overhead. -

Louis XIV of France King at 4 years, 8 months (1643)

Louis XIV became king as a small child, with his mother and key ministers guiding France during his early years. That childhood wasn’t peaceful: France faced

internal unrest during his minority, and the experience shaped his later approach to power. His adulthood would become synonymous with absolute monarchy, but the

“Sun King” began as a boy surrounded by adults who understood that controlling the court often meant controlling the kingdom. -

Ptolemy V Epiphanes of Egypt King at 5 years old (204 BCE)

Ptolemy V inherited a complex and fragile empire as a child. In his reign, Egypt faced uprisings and external pressures, and royal authority had to be asserted

through ceremony, decrees, andoftenforce carried out by adults in his name. His era is linked to the famous Rosetta Stone decree, a reminder that “child king”

doesn’t mean “quiet reign.” It can mean a scramble to project stability when the throne is occupied by someone still learning basic arithmetic. -

Michael I of Romania King at 5 years old (1927)

Michael I became king while still a child due to a complicated political situation in Romania’s monarchy. A regency governed, and later events would bring him

back into power again. His life illustrates how “being king” can be less about a continuous, all-powerful reign and more about constitutional structures,

shifting alliances, and the unpredictable way history treats monarchs who inherit instability instead of a settled state. -

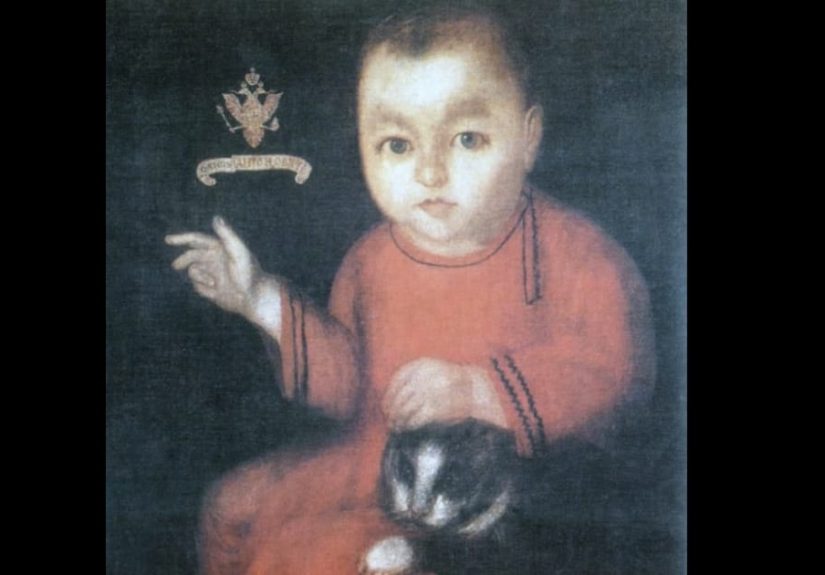

Pepi II of ancient Egypt Traditionally placed around age 6 at accession (c. 23rd century BCE)

Pepi II is often described as coming to the throne as a young child and ruling for an extraordinarily long time. Ancient chronologies can be complex, and exact

ages are not always firm the way modern birth records are. Still, Pepi II belongs on any serious list of child monarchs because his reign

represents a classic ancient pattern: a young king, a governing circle of adults, and an empire that must keep functioning even when the person at the top is

far too young to personally steer it. -

Simeon II of Bulgaria King at 6 years old (1943)

Simeon II became king when he was six, with Bulgaria facing immense pressure during World War II and its aftermath. A regency oversaw his reign, but the

monarchy was later abolished and Simeon went into exile. His story is a powerful reminder that being “the rightful king” can be historically meaningful while

being politically powerlessespecially when world events move faster than any royal institution can adapt. -

Josiah of Judah King at 8 years old (7th century BCE)

According to historical and biblical traditions, Josiah became king at eight and later became known for major religious reforms. Whether you approach his story

from religious history, political history, or both, Josiah illustrates a key truth about child kings: their reigns can start in vulnerability and still become

culturally defining. A young accession doesn’t automatically predict a weak legacysometimes it’s the beginning of a transformative rule once the king comes of age. -

Tutankhamun (“King Tut”) Became king around age 9 (c. 14th century BCE)

Tutankhamun may be the world’s most famous “boy king,” largely because his tomb survived with astonishing riches. He became king young, in the shadow of major

religious and political upheaval following Akhenaten’s reign. Adults and advisors likely played major roles in steering policy, but Tut’s reign still mattered:

it marked a return to older religious traditions and set the stage for later power struggles. In other words, even when the king is a kid, the kingdom doesn’t stop being complicated.

What These Child Kings Reveal About Power

Put these reigns side by side and a pattern appears: a child king is rarely the “decision-maker” at first. He is the legal and symbolic anchor while older hands

move the levers of government. That arrangement can create stabilitybecause it avoids a succession crisisbut it can also supercharge conflict, because it creates

a vacuum at the top where ambitious people compete to become the real authority.

Child kings also highlight how monarchy depends on storytelling. When the ruler is too young to command an army, negotiate treaties, or deliver policy, the state

leans harder on ritual, imagery, and tradition. Coronations become louder. Titles get longer. Coins and proclamations become political billboards. The message is

simple: “The crown is continuous, even if the king is still on training wheels.”

How Historians Talk About “Youngest Kings” Without Getting Tripped Up

A quick reality check: there are many child monarchs across history, and the “youngest” label depends on definitions. Was the king proclaimed at birth

but crowned later? Did he reign only in name during a regency? Are we including pharaohs and ancient rulers under the broad idea of “king,” even when the titles differ?

The safest approach is transparencystate the age as clearly as possible, note whether it’s an estimate, and focus on what the early reign meant politically.

That’s also why lists like this are more valuable as analysis than as a scoreboard. The point isn’t to crown the “world champion baby king.”

The point is to understand how societies built systems where a child could be the top symbol of governmentand how adults fought over what that symbol allowed them to do.

Reader Experiences: What It Feels Like to Step Into the World of the Youngest Kings

Reading about the youngest kings in history can feel oddly personal, because the ages don’t stay abstract for long. “King at nine months” lands differently once you

picture a modern nine-month-oldcurious, wobbly, and more interested in trying to eat a spoon than signing a treaty. That mental comparison is often the first “click”

moment for readers: monarchy suddenly stops feeling like distant pageantry and starts feeling like a human system with human absurdities.

If you’ve ever walked through a museum gallery of royal artifactstiny rings, miniature crowns, portraits of solemn children dressed like adultsyou know the strange

emotional mix it creates. On one hand, it’s beautiful: gold, velvet, painstaking craftsmanship. On the other, it’s unsettling. The portraits often show boys posed like

seasoned rulers, but their faces give them away. The eyes say, “I was promised a pony,” while the clothing says, “Here is your empire.”

Even without traveling, you can get a similar effect from primary sources and historical storytelling. Letters written by regents, court records, or chronicles describing

coronations often contain little details that hit harder than the big events. Who carried the child into the ceremony? Who stood closest to the throne? Which noble families

were suddenly promoted, and which ones disappeared from the record? Those details are the fingerprints of a regency at work: adults rearranging power while insisting the king

is fully in charge (because the story has to hold).

There’s also a practical “reader experience” that shows up again and again: you start noticing how often child kings appear at moments of crisis. Once you’ve read a few of

these biographies, a pattern emerges in your brain like a historical weather forecast. A monarch dies unexpectedly. The heir is a minor. A regent council forms. Factions

gather. Someone whispers that the child isn’t legitimate (or that the regent is too powerful). And suddenly you realize you’re not just reading royal triviayou’re watching

a system stress-test itself in real time.

And yes, sometimes it’s hard not to imagine the daily logistics. Picture a royal tutor trying to teach Latin declensions while ministers argue about borders. Or a nursemaid

soothing a crying infant while courtiers bow and call him “Your Majesty.” That contrastbetween childhood needs and adult powercreates the emotional voltage that makes these

stories stick. The youngest kings remind us that history isn’t only made by the loudest speeches and biggest battles. Sometimes it’s made by who stood beside a cradle, who

held the regency seal, and who convinced everyone that the crown’s authority could fit on the head of a child.

Conclusion

The youngest kings in history prove something both dramatic and oddly modern: institutions can be unbelievably resilient, even when leadership is unbelievably young.

Whether a king inherited the throne at birth, at six months, or at eight years old, the state still needed laws enforced, taxes collected, enemies deterred, and legitimacy

performedsometimes more intensely than ever. Behind the famous names and famous crowns, the real story is often the same: a child at the center, and a whole adult world

fighting to define what his reign would mean.