Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- 1) The Sunk Cost Fallacy: “I’ve Already Spent This Much, So I Have to Keep Going.”

- 2) The Bandwagon Fallacy: “Everyone’s Doing It, So It Must Be Smart.”

- 3) Appeal to Authority: “A Famous/Confident Person Said It, So It Must Be Right.”

- 4) The False Dilemma (False Dichotomy): “It’s Either This or That.”

- 5) Hasty Generalization: “One Story = A Universal Rule.”

- 6) Post Hoc (False Cause): “This Happened After That, So That Must Have Caused It.”

- Putting It All Together: A 60-Second “Fallacy Audit” Before You Spend

- Experiences: 6 Everyday Money Moments Where Fallacies Sneak In (About )

If money had a sound, logical fallacies would be that tiny “cha-ching” you hear right before your bank balance sighs.

Not because you’re “bad with money,” but because your brain is busy doing what brains do best: saving effort.

The problem is that shortcuts in thinking can turn into shortcuts out of your walletespecially when ads, influencers,

sales scripts, and even your own past decisions push the right emotional buttons.

This article breaks down six common reasoning errors (logical fallacies) that sneak into everyday spending and investing.

You’ll get clear definitions, real-world examples, and practical “do this instead” moves you can use immediatelyno finance degree,

no spreadsheet-induced tears.

1) The Sunk Cost Fallacy: “I’ve Already Spent This Much, So I Have to Keep Going.”

What it is: Treating past costs (money, time, effort) as a reason to keep payingeven when the best move today is to stop.

The money is gone either way, but your brain tries to “rescue” it by spending more.

How it costs you money: You keep a subscription you don’t use because you paid for the annual plan.

You keep repairing an old car because you’ve “put too much into it.”

You hold a bad investment because selling would “lock in the loss,” as if the market is waiting to reward your loyalty with a trophy.

Spoiler: it is not.

A painfully relatable example: You buy an online course. Week one is great. Week two is… confusing.

Week three is a 90-minute video that could’ve been a sticky note. But you keep watching because “it was expensive.”

Congratsyou just turned a sunk cost into a monthly time-tax and a guilt subscription.

How to dodge it

- Ask the only question that matters: “If I hadn’t spent a dime yet, would I buy/keep this today?”

- Set a “stop-loss” rule for life: Decide in advance what makes you quit (price cap, time cap, results deadline).

- Rename the feeling: It’s not “wasting money,” it’s “buying information.” You learned it’s not worth more spending.

2) The Bandwagon Fallacy: “Everyone’s Doing It, So It Must Be Smart.”

What it is: Assuming something is good, true, or a good deal because it’s popular.

Popularity can be a cluebut it’s not evidence of fit for your budget, needs, or goals.

How it costs you money: “Trending” becomes a shopping category.

You buy the viral water bottle, the must-have kitchen gadget, the “everyone has it” skincare routine,

and suddenly your cart looks like it got peer-pressured at a middle school dance.

Money example: You see a flood of “I switched to this bank/credit card/app and my life changed” posts.

You sign up, miss the fine print, pay a fee, and realize the “life change” was mostly for the affiliate marketer.

How to dodge it

- Run the “3 Filters” test: Do I need it? Will I use it weekly? Is it worth it after fees, accessories, and add-ons?

- Wait 72 hours for anything “viral”: If it’s still useful after the hype wears off, it’s probably real.

- Create a “Not For Me” list: Categories you don’t buy on impulse (gadgets, courses, beauty bundles, limited drops).

3) Appeal to Authority: “A Famous/Confident Person Said It, So It Must Be Right.”

What it is: Accepting a claim as true because an authority figure (or someone who looks like one) says it.

Sometimes experts are worth listening to. The fallacy shows up when the “authority” isn’t relevantor when you skip evidence.

How it costs you money: You buy a supplement because a celebrity says it works.

You jump into an investment because a charismatic “finance guru” says it’s a “can’t miss.”

You follow a loud person with a microphone and mistake volume for validity.

Financial reality check: Regulators have repeatedly warned investors not to rely on celebrity endorsements

when making investment decisions. Fame is not a license, and “I’m partnered with…” is not a risk disclosure.

How to dodge it

- Ask “Authority of what?” A great athlete can be an authority on trainingnot necessarily on tokenomics.

- Look for incentives: Are they paid? Do they benefit if you buy/subscribe/invest?

- Use the “Two-Source Rule”: Don’t act until you confirm the claim from two independent, reputable sources.

4) The False Dilemma (False Dichotomy): “It’s Either This or That.”

What it is: Acting like there are only two options when there are actually many.

Your brain loves simple choices. Marketers love them even more.

How it costs you money:

“Either I buy the premium plan or it’s pointless.”

“Either I do the perfect budget or I shouldn’t bother.”

“Either I fix the car completely or I need a brand-new one.”

Then you choose the most expensive “either,” because the “or” sounds like failure.

Everyday example: You want to start saving. Your brain proposes two options:

(1) Save $1,000 a month like a financial superhero, or (2) give up and buy snacks.

The middle pathsave $50 this week, automate $10/day, renegotiate one billgets ignored, even though it’s the one that works.

How to dodge it

- Add a third option on purpose: “What’s a cheaper, smaller, or temporary version of this?”

- Use “good-better-best” budgeting: A minimal plan (good), a realistic plan (better), and an ambitious plan (best).

- Replace “either/or” with “how can I”: “How can I get 80% of the benefit for 20% of the cost?”

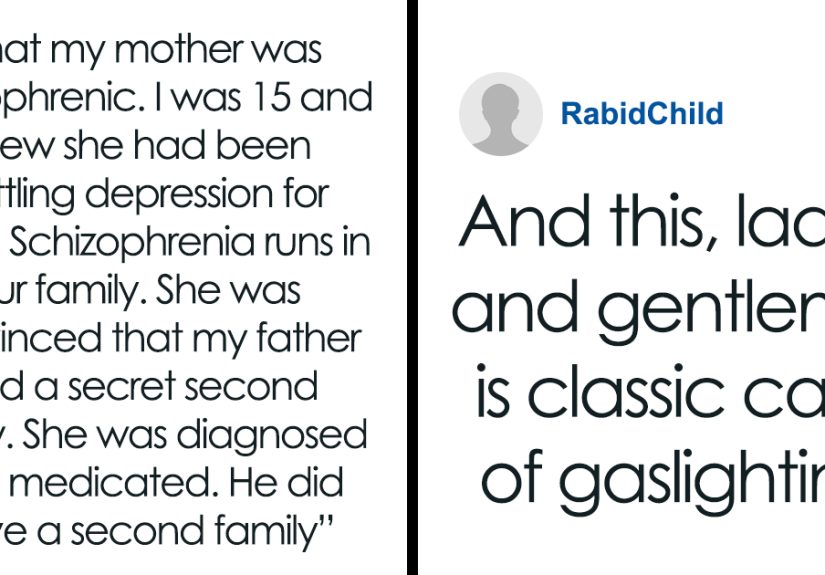

5) Hasty Generalization: “One Story = A Universal Rule.”

What it is: Making a big conclusion from a small or unrepresentative sample.

One friend’s experience becomes “proof,” and one headline becomes “the whole truth.”

How it costs you money: You try one budgeting app, hate it, and decide budgeting “doesn’t work.”

You buy one cheap tool that breaks and decide “cheap products are always trash,” so you overpay forever.

You pick one stock that went up and conclude you’re basically a market wizardthen you double down and learn humility the expensive way.

Sneaky version: Reviews. A handful of glowing reviews can be real…

or it can be a product with a small group of loud fans (or, let’s be honest, a coupon army).

A handful of angry reviews might be user error, shipping damage, or unrealistic expectations.

Small samples are emotionally loud and statistically quiet.

How to dodge it

- Scale up the sample: Look for patterns across many reviews and multiple sources.

- Separate the product from the situation: “This didn’t work for them” isn’t “this never works.”

- Use a tiny experiment: Before a big purchase, test a cheaper version or a limited-time trial.

6) Post Hoc (False Cause): “This Happened After That, So That Must Have Caused It.”

What it is: Assuming causation just because one event came before another.

Timing is not proof. It’s just timing.

How it costs you money: You buy a “money mindset” course and then get a raise two weeks later.

The raise might be because your annual review landed… annually.

You switch shampoos and your hair looks better because you also stopped blow-drying it at volcano temperature.

You pick an investment that rises during a market rally and conclude your method is flawlessright until the market stops cooperating.

Why it’s dangerous: False cause builds superstition into your finances.

You start paying for “lucky” systems, not proven oneschasing signals that were actually coincidence.

How to dodge it

- Ask “What else changed?” Sleep, season, economy, promotions, interest rates, deadlineslife is noisy.

- Look for repeatability: If a strategy works, it should work more than once and under different conditions.

- Use simple tracking: A note on what you changed and what happened prevents your brain from rewriting history.

Putting It All Together: A 60-Second “Fallacy Audit” Before You Spend

Next time you’re about to buy, upgrade, subscribe, or invest, run this quick checklist:

- Sunk cost: “Would I start this today at this price?”

- Bandwagon: “If nobody posted about it, would I still want it?”

- Authority: “Are they qualifiedand are they incentivized?”

- False dilemma: “What’s my third option?”

- Hasty generalization: “Am I overreacting to one story?”

- Post hoc: “Do I have evidence it caused the outcome?”

The goal isn’t to become a robot. (Robots don’t have to pay for streaming bundles they forgot aboutlucky.)

The goal is to notice when your brain is substituting a feeling for a fact. That tiny pause is where better money habits live.

Experiences: 6 Everyday Money Moments Where Fallacies Sneak In (About )

Moment #1: The subscription you “might use later.” You’re cleaning up your bank statement and spot a subscription you forgot.

Your first reaction is annoyance. Your second reaction is surprisingly protective: “But I’ve had it for months.”

That’s the sunk cost fallacy putting on a little helmet and trying to defend past-you’s decision.

A better question shows up when you’re calm: “If I saw this charge today for the first time, would I sign up?”

If the answer is no, canceling isn’t “wasting money.” It’s preventing future waste.

Moment #2: The “everyone is buying it” deal. You see a limited drop and your group chat is buzzing.

Half the excitement is the product; the other half is belonging.

Bandwagon fallacy turns social energy into spending energy. You buy fast to avoid being the only one without it.

Two weeks later it’s in a drawer, living its best life as a dust collector.

The fix isn’t to stop enjoying trendsit’s to separate “fun to watch” from “worth owning.”

Moment #3: The confident expert who isn’t an expert. A creator points at a chart, speaks quickly, and says,

“This is what the rich do.” You feel like you’re getting insider knowledge.

Appeal to authority thrives on confidence, production quality, and fancy words that sound expensive.

The best counter-move is boring, which is why it works: check credentials, look for disclosures, and confirm with reputable sources.

If the pitch discourages questions (“Haters don’t get it”), treat that as a blinking warning light.

Moment #4: The all-or-nothing budget crash. You overspend one weekend and immediately conclude,

“Welp, I ruined the month.” That false dilemma offers two choices: perfect or pointless.

Real budgets aren’t fragile glass sculptures. They’re steering wheels.

If you took a wrong turn, you don’t set the car on fireyou adjust.

One practical habit: build a “messy life” category (birthdays, surprise fees, the occasional emotional burrito).

Moment #5: One review convinces you forever. You buy a cheap gadget once and it breaks. Now you swear off all budget brands.

Or you buy one premium product and it’s amazing, so you assume higher price always means higher value.

That’s hasty generalization turning one data point into a lifelong pricing policy.

Instead, look for consistent patterns across many reviews, return rates, and reputable testing.

Sometimes “mid-range” is the true luxury: it works and you don’t feel personally offended by the receipt.

Moment #6: The “strategy” that worked once. You invest, it goes up, and your brain says,

“Clearly I have cracked the code.” That’s post hoccrediting your method when the market might have carried you.

The expensive sequel is overconfidence: bigger bets, less diversification, and a refusal to accept randomness.

A calmer approach is to track decisions and reasons, then review outcomes later.

If the reason was “vibes,” don’t upgrade your bet sizeupgrade your evidence.