Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Pancreatic Cancer Triggers Big Fear (And Why That Fear Makes Sense)

- What Trebek Did Differently: Turning a Scary Diagnosis into a Clear Message

- Pancreatic Cancer 101 (Because Googling at 2 a.m. Is a Trap)

- Symptoms and Early Warning Signs: What to Notice (Without Spiraling)

- Risk Factors: The Stuff You Can’t Changeand the Stuff You Can

- Can Pancreatic Cancer Be Found Early?

- Treatment Has Evolved: What “Fighting It” Can Actually Look Like

- Going Beyond Fear: A Calm, Useful Action Plan

- How to Support Someone Who’s Facing Pancreatic Cancer (Without Saying Weird Stuff)

- A Trebek-Style Ending: What We Do with Fear Matters

- Experiences That Echo Trebek’s Message (500+ Words)

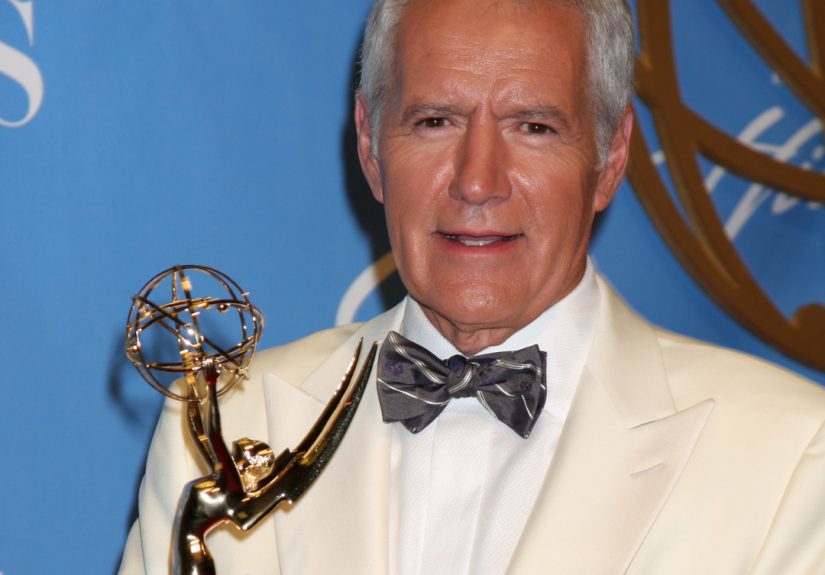

When Alex Trebek told the world he had stage IV pancreatic cancer, he didn’t just deliver newshe delivered a masterclass in how to stare down fear without letting it drive the car.

He looked straight at the camera, acknowledged the tough odds, and essentially said: “Okay. Now let’s do the work.”

If you’ve ever felt your stomach drop after hearing the words pancreatic cancerin a headline, a family story, or a doctor’s officeyou’re not alone.

This disease has a reputation, and it’s not exactly a warm hug.

But Trebek’s message (and the conversations it sparked) points to something useful: fear can be a signal, not a sentence.

Fear can say, “Pay attention.” It does not have to say, “Give up.”

Let’s use that energy the way Trebek would: clear-eyed, practical, andwhen possiblesprinkled with a little humor, because humans aren’t robots and neither was he.

Why Pancreatic Cancer Triggers Big Fear (And Why That Fear Makes Sense)

Pancreatic cancer is often diagnosed late because early-stage disease may not cause obvious symptoms, and the pancreas sits deep in the abdomen where problems can hide for a while.

That “late discovery” reality fuels the statistics people quoteand the dread they feel.

Overall survival has been improving gradually, but it still lags behind many other cancers, especially when the disease is found after it has spread.

Here’s the important nuance: survival rates aren’t personal prophecies. They’re averages across large groups, reflecting stage at diagnosis, tumor biology, access to specialized care,

and treatment advances that keep evolving. The stage matters a lotlocalized disease has far better outcomes than distant (metastatic) disease.

That’s not “false hope.” That’s “context.”

What Trebek Did Differently: Turning a Scary Diagnosis into a Clear Message

Trebek didn’t pretend pancreatic cancer was easy. He also didn’t treat it like a magical curse.

He talked about support from family and friends, he kept working as long as he could, and he gave people something to do with their worry:

show up, learn, and care about earlier detection and better treatment.

Even if you’re not facing cancer personally, his approach offers a roadmap:

name the fear, don’t feed the fear, and then take the next right step.

It’s not dramatic. It’s not viral. It’s just effective.

Pancreatic Cancer 101 (Because Googling at 2 a.m. Is a Trap)

The pancreas is a gland behind the stomach that helps you digest food (enzymes) and regulate blood sugar (hormones like insulin).

Most pancreatic cancers are “exocrine” cancersoften pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC).

There are also less common pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), which behave differently and often have different treatment paths.

When clinicians talk about “stage,” they’re describing how far the cancer has spread.

Early-stage (localized) cancers may be removable with surgery. More advanced cancers may require chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation in select cases,

and strong symptom-focused care to protect quality of life.

Symptoms and Early Warning Signs: What to Notice (Without Spiraling)

Pancreatic cancer symptoms can be vague, and many are caused by far more common (and less serious) conditions.

Still, some patterns deserve attentionespecially if they are new, persistent, worsening, or show up in combination.

Common signs doctors take seriously

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes), often with dark urine or light-colored stools

- Upper abdominal pain that may radiate to the back

- Unintended weight loss and decreased appetite

- Ongoing fatigue

- Nausea, indigestion, or bloating that doesn’t resolve

- New-onset diabetesespecially later in life or with unexplained weight loss

A key Trebek-style takeaway: you don’t need to diagnose yourself. You just need to notice what’s changed and bring it to a clinician who can evaluate it.

If you develop jaundice, don’t “wait and see.” That’s a “call today” symptom.

Risk Factors: The Stuff You Can’t Changeand the Stuff You Can

Fear says, “This is random, so I’m powerless.” Reality is more balanced.

Some risk factors are out of your control, but others are modifiableand even the unchangeable risks can guide smarter surveillance for people at higher risk.

Risk factors you can’t change

- Age (risk rises as people get older)

- Family history of pancreatic cancer

- Inherited genetic syndromes (for example, certain mutations that raise cancer risk)

- Personal history of certain pancreatic conditions

Risk factors you may be able to change or reduce

- Smoking (one of the strongest modifiable risk factors)

- Excess body weight and central obesity

- Diabetes management (especially paying attention to sudden changes)

- Heavy alcohol use (often through its relationship with pancreatitis and overall health)

This is where “going beyond fear” becomes concrete. You don’t need a perfect lifestyle. You need a realistic plan:

stop smoking (or don’t start), aim for sustainable weight and activity habits, keep regular primary care visits, and take family history seriously.

None of that is flashy. All of it is meaningful.

Can Pancreatic Cancer Be Found Early?

For the general population, there is no standard screening test like a routine mammogram or colonoscopy.

That’s partly because pancreatic cancer is relatively uncommon compared with many screened cancers, and screening tests must be accurate enough to avoid harming people through false alarms and unnecessary procedures.

But for people at high risksuch as those with a strong family history or certain inherited syndromesspecialized programs may recommend surveillance.

Common tools include MRI/MRCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), typically at centers experienced in pancreatic disease.

Research continues into better early detection methods, including studying links between blood sugar changes and pancreatic cancer.

A practical checkpoint

If multiple close relatives have had pancreatic cancer, or if pancreatic cancer is showing up alongside patterns like breast/ovarian/prostate cancers in the family,

ask your doctor about genetic counseling and whether high-risk surveillance makes sense.

This is not about panic. It’s about precision.

Treatment Has Evolved: What “Fighting It” Can Actually Look Like

“Fight” is an emotional word, and it can be inspiringbut it shouldn’t pressure anyone to be a superhero.

In real life, treatment is more like a long season of training: planning, adjustments, rest, teamwork, and sometimes a change in strategy.

Common treatment approaches (depending on stage and tumor biology)

- Surgery for cancers that can be removed (often paired with chemotherapy before and/or after)

- Chemotherapy as a backbone treatment for many stages

- Radiation in selected situations, often as part of a combined strategy

- Targeted therapies for specific tumor features (when present)

- Immunotherapy for the small subset of tumors with particular biomarkers

- Clinical trialsimportant at every stage, not just “last resort”

- Palliative care (supportive care) to reduce symptoms and protect quality of lifehelpful early, not only late

One of the most Trebek-ish reframes is this: a “second opinion” isn’t an insult to your doctor.

It’s you doing your homeworklike checking a Daily Double before you wager your whole board.

Pancreatic cancer care can be complex, and high-volume cancer centers often have multidisciplinary teams that see these cases every day.

Going Beyond Fear: A Calm, Useful Action Plan

Fear loves vagueness. It whispers, “Something bad could happen,” and then refuses to specify what you can do about it.

So let’s outsmart fear with specificity.

1) Know your family story (and write it down)

- Which relatives had cancer?

- What types (pancreatic, breast, ovarian, colon, melanoma, prostate)?

- Rough ages at diagnosis?

This isn’t small talk. It can determine whether genetic counseling or high-risk surveillance is appropriate.

2) Protect the basics that matter most

- If you smoke: get help quitting (it’s hard; it’s worth it)

- Build a realistic activity routine (walking countsyour pancreas isn’t grading your form)

- Keep routine checkups and labs, especially if you have diabetes or strong family history

- Limit heavy alcohol use and address pancreatitis risk with your clinician

3) Don’t ignore body “plot twists”

New jaundice, unexplained weight loss, persistent upper abdominal/back pain, or sudden changes in blood sugar deserve medical evaluation.

That doesn’t mean cancer. It means your body is asking for attention.

How to Support Someone Who’s Facing Pancreatic Cancer (Without Saying Weird Stuff)

If someone you love is dealing with this disease, your support can be a real form of medicinejust without the side effects list.

A few practical moves:

- Offer specific help: “I can drive you Tuesdays,” beats “Let me know if you need anything.”

- Be the note-taker at appointments (information overload is real).

- Ask about symptoms and comfort, not just scan results.

- Respect the person’s tone: some want humor, some want quiet, many want both depending on the day.

- Encourage expert care and trial explorationwithout nagging.

Also: if they make a joke, you’re allowed to laugh. Humor isn’t denial; it’s oxygen.

A Trebek-Style Ending: What We Do with Fear Matters

Alex Trebek didn’t become a symbol because he was fearless. He became a symbol because he was honest about the fearand moved forward anyway.

Pancreatic cancer is serious. It can be devastating. It also isn’t a reason to live frozen.

Going beyond fear doesn’t mean pretending everything is fine. It means trading doom-scrolling for real steps:

learn the warning signs, understand risk, protect the basics, talk to your doctor when something changes, and support research and clinical trials that push outcomes forward.

That’s how progress happensone practical decision at a time.

Experiences That Echo Trebek’s Message (500+ Words)

The first time “pancreatic cancer” enters most people’s lives, it doesn’t arrive politely. It kicks the door in.

One caregiver described it as hearing a word that instantly changed the temperature in the room.

They weren’t thinking about enzymes or anatomy. They were thinking about timehow much, how little, and how unfair it felt to even ask.

That’s fear doing what fear does: turning the future into a single, terrifying snapshot.

But something interesting happens when people move from fear into action: the snapshot becomes a timeline again.

Not an easy timeline, not a guaranteed onebut a real one with choices, supports, and moments that aren’t just medical.

A woman whose dad developed jaundice remembered the strange clarity of that day.

She didn’t “Google and guess.” She called the doctor, pushed for evaluation, and later said she was grateful she didn’t waste weeks bargaining with herself.

Even before they knew the diagnosis, she felt a shift: “I can’t control what this is,” she said, “but I can control what we do next.”

That’s the difference between fear as a warning light and fear as the steering wheel.

Another experience comes from people who notice subtler changes: fatigue that doesn’t match their life, appetite that disappears, blood sugar that suddenly misbehaves.

One man joked that he thought he was just getting older“My warranty expired,” he told his spouse.

It was a joke, but it was also a cover for worry.

What helped him wasn’t pretending the worry didn’t exist. It was a clinician who treated his concerns seriously without catastrophizing:

“Let’s run the right tests,” the doctor said, “and let’s not borrow trouble from outcomes we don’t have.”

That calm competence is underrated. It’s also contagious. Fear shrinks when the plan grows.

People in treatment often describe an emotional whiplash: hopeful one week, exhausted the next.

They learn quickly that courage isn’t a permanent personality traitit’s a repeated decision.

Some days, courage looks like showing up for chemotherapy.

Other days, it looks like letting someone else drive, taking the nap, and eating what you can tolerate without turning every meal into a moral achievement.

(If anyone tries to shame you about a milkshake during chemo, you have permission to unfollow them in real life.)

Families also discover how support actually works.

It’s not inspirational speeches. It’s logistics: rides, meals, childcare, pharmacy runs, and sitting in silence without trying to “fix” the mood.

A friend of a patient once said, “I didn’t know what to say, so I brought a calendar.”

They coordinated help like a small, loving operations team. That kind of support doesn’t erase fear, but it makes fear less lonelyand loneliness is the part that breaks people.

Trebek’s public openness mattered because it gave permission for honest conversations.

It reminded people that you can acknowledge the statistics while still insisting on dignity and effort.

Many families, after the initial shock, choose one guiding principle: we don’t control the whole story, but we do control today’s chapter.

Today’s chapter might be a second opinion at a specialized center, a talk about clinical trials, or simply a good breakfast and a walk to the mailbox.

Those chapters add up. And when fear tries to shrink life to a single terrible headline, that daily practicesteady, imperfect, humanpushes life back open.