Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why “rare” historical photos hit differently

- The Camera Learns to Time-Travel (1840s–1890s)

- 1843: John Quincy Adams, the earliest photographed U.S. president

- 1860: Abraham Lincoln before the big speeches

- Mid-1800s: Black photographers building their own lens on America

- 1869: The Golden Spike at Promontory Summit

- 1876–1884: The Statue of Liberty being built in pieces

- 1883: The Brooklyn Bridgenew skyline, new confidence

- Building the Modern World (1900s–1930s)

- Work, Weather, and World War (1930s–1940s)

- 1932: “Lunch atop a Skyscraper” (and the frames you rarely see)

- c. 1934: The Golden Gate Bridge mid-build

- 1936: Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and its wider story

- 1930s–1941: Mount Rushmore under construction

- 1942–1944: Manzanar documented by Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams

- 1945: Raising the flag on Iwo Jimaicon, controversy, reality

- Rights and Rockets (1950s–1970s)

- 1957: The Little Rock Nine walking into history

- 1960: Greensboro sit-instillness as protest

- 1963: March on Washington crowds (and the “extra” photos that survived)

- 1968: “Earthrise” from Apollo 8

- 1969: Buzz Aldrin on the Moon (and the bootprints of a new era)

- 1972: The “Blue Marble”Earth as a single, shared home

- From Ash Clouds to Archive Rediscoveries (1974–2001)

- 1974: Nixon’s departureone frame, a whole political mood

- 1980: Mount St. Helenswhen a camera (and film) survives the chaos

- 1989: The Berlin Wall coming downhistory in motion

- 1995: The Hubble Deep Field“rarely seen” as a scientific achievement

- 2001: “Raising the Flag at Ground Zero”

- 2001: The lesser-known Ground Zero frame that complicates memory

- How to look at historical photographs without inventing a movie plot

- Experience: What it feels like to time-travel through rarely seen photos (and why you’ll get hooked)

- Conclusion

If history class ever felt like a long list of dates trying to pick a fight with your attention span, historical photographs are the

sweet revenge. A single image can turn “the past” into a real place with real faceswrinkled work gloves, nervous smiles, muddy boots,

and the occasional hat that looks like it was designed by someone who lost a bet.

And the best part? The photos that stick with you aren’t always the most famous ones. Sometimes it’s an “extra” frame from a well-known

moment, a behind-the-scenes angle, or a quiet snapshot that survived in an archive long enough to tap you on the shoulder and say,

“Hey. I was there.”

Why “rare” historical photos hit differently

Rarely seen photos do two things at once: they confirm what we already know (yes, the Golden Spike ceremony was real), and they complicate it

(look closerwho’s missing, who’s centered, who’s working, who’s posing). They also remind us that every photo is a choice: where the camera stood,

what it included, what it cropped out, and what someone decided was worth saving.

Below are 30 people, places, and eventsorganized by eracaptured in photographs that feel fresh even when the facts are old.

Think of it as a museum stroll, except you can wear sweatpants and nobody shushes you.

The Camera Learns to Time-Travel (1840s–1890s)

-

1843: John Quincy Adams, the earliest photographed U.S. president

Before selfies, there were daguerreotypesglittery, mirror-like images that required you to sit very still, like a Victorian statue audition.

One of the earliest presidential portraits captured John Quincy Adams, proof that even in the 1840s, America loved a good “official photo.” -

1860: Abraham Lincoln before the big speeches

Portrait photography turned politicians into recognizable faces, not just names in newspapers. Lincoln’s studio portraits helped shape how the public

“met” himserious, slightly weary, and unmistakably human. It’s a reminder that image-making in politics didn’t start with modern media. -

Mid-1800s: Black photographers building their own lens on America

Early photography wasn’t just a technical revolutionit was a social one. Black-owned studios and Black photographers created dignified portraits that

challenged stereotypes and preserved community history on their own terms. These images feel radical because they are: self-definition, in silver and light. -

1869: The Golden Spike at Promontory Summit

The famous “joining of the rails” photo looks like a party, but it’s also a snapshot of industrial ambitionlocomotives nose-to-nose, officials posing,

workers nearby, and a nation celebrating speed. Look for the tension between ceremony and labor: who gets named, and who gets blurred into “the crew.” -

1876–1884: The Statue of Liberty being built in pieces

Lady Liberty didn’t arrive fully assembled like a monument from a shipping crate. Parts were constructed in France, displayed to raise funds, then completed

and assembled in Paris before crossing the Atlantic. Construction photos make her feel less like an icon and more like an engineering project with bolts, scaffolding,

and very patient craftspeople. -

1883: The Brooklyn Bridgenew skyline, new confidence

Early bridge photos show a city trying on modernity. The Brooklyn Bridge wasn’t just a commute upgrade; it was a flex. Images from the era capture the structure

as both infrastructure and spectaclepeople gathering to stare at it the way we stare at rocket launches today.

Building the Modern World (1900s–1930s)

-

1903: The Wright brothers’ first flight, caught on camera

The photo of the first powered flight is wonderfully unglamorous: a fragile machine, a sandy stretch of ground, and a moment that looks almost accidental.

That’s the magic. It doesn’t look like “the future”which is exactly why it’s believable. -

1905–1920: Ellis Island portraits by Augustus F. Sherman

These portraits feel like introductions. Immigrants pose in clothing that signals homeland, trade, tradition, and prideoften photographed by an Ellis Island

clerk who understood the power of a face with a name and a story. Even when the sitters are unnamed, the images insist: this is what arrival looked like. -

1906: San Francisco after the earthquake

Earthquake photographs are eerie because the streets are familiarbut rearranged. Rubble, tilted facades, and crowds standing in open space show how a city becomes

temporary overnight. These images also capture something quietly heroic: people adapting in real time, before anyone has a plan. -

1904–1914: Panama Canal construction snapshots

Canal photos are a study in scale: massive earthworks, machinery, and workers living in makeshift communities under tough conditions. What makes some archival albums

feel “rare” is their casualnessless propaganda, more daily lifelike someone saying, “Here’s what I saw on my walk to work.” -

1913: The Women’s Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C.

Parade photos capture strategy in motion: banners, coordinated outfits, and the deliberate choice to occupy public space. The camera freezes the moment when persuasion

turns into presencewhen the message is not just spoken, but staged, marched, and photographed into the record. -

1920s: Harlem Renaissance studio portraits

Studio photography during the Harlem Renaissance wasn’t just “a nice picture.” It was style as statement. Sharp suits, confident posture, and careful lighting

broadcast possibilitymodern identity, modern art, modern lifemade visible at a time when visibility itself carried risk.

Work, Weather, and World War (1930s–1940s)

-

1932: “Lunch atop a Skyscraper” (and the frames you rarely see)

You’ve seen the famous beam-lunch photo. What’s less talked about is that it was part of a whole publicity shootmultiple poses, multiple angles, and a very

deliberate “look how fearless we are” vibe. It’s a reminder that even iconic images can be staged while still revealing real working conditions. -

c. 1934: The Golden Gate Bridge mid-build

Construction photos of the Golden Gate Bridge feel impossible: cables, towers, and open sky, with the bay below like a dare. Archival shots show the bridge as a

living processunfinished geometrybefore it became a postcard. The “rare” feeling comes from seeing a landmark still becoming itself. -

1936: Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” and its wider story

The most famous frame is only one part of a series. Looking at the context around itwhat came before and afterturns a symbol into a person with a complicated,

often misunderstood history. The photo endures because it forces empathy without giving easy answers. -

1930s–1941: Mount Rushmore under construction

Photos from Mount Rushmore’s carving are a “how is that even real?” momentworkers hanging from ropes, drilling into a mountainside with precision and nerve.

These images show monuments as human labor, not magic, and they raise questions about what (and whose) stories get carved into the landscape. -

1942–1944: Manzanar documented by Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams

Photographs from Manzanar capture ordinary life inside an extraordinary injustice: people waiting, working, studying, and building routines under forced confinement.

Some of the most affecting images aren’t dramaticthey’re domesticbecause they show how people tried to live with dignity under pressure. -

1945: Raising the flag on Iwo Jimaicon, controversy, reality

This photograph became shorthand for sacrifice and victory, but the battle continued long after the shutter clicked. Rarely discussed detailslike how quickly the

image traveled and how powerfully it shaped public emotionshow that a photo can be both true and incomplete at the same time.

Rights and Rockets (1950s–1970s)

-

1957: The Little Rock Nine walking into history

Some civil rights photos feel like a turning point captured mid-step: a student walking, books held close, expression steady, while a crowd reacts around them.

The “rarely seen” power is in the surrounding detailsfaces, spacing, postureshowing how courage can look quiet from the outside. -

1960: Greensboro sit-instillness as protest

Sit-in photographs are deceptively calm: people seated, waiting, refusing to move. That calm is the point. The camera captures disciplinehands folded, eyes forward

and the tension created by doing something incredibly disruptive while appearing completely composed. -

1963: March on Washington crowds (and the “extra” photos that survived)

Wide crowd shots turn a single speech into a national moment: thousands gathered, packed together, looking toward a shared horizon. Some lesser-known photos were

rediscovered years later, which is a good reminder that archives aren’t statichistory keeps turning up in boxes, trunks, and mislabeled folders. -

1968: “Earthrise” from Apollo 8

Earthrise is famous, but it still feels new every time: our planet hovering above the Moon’s horizon, fragile and bright. The “rare” sensation comes from realizing

this was the first time humans saw that view directlyand a photographer had the reflex to point the camera home. -

1969: Buzz Aldrin on the Moon (and the bootprints of a new era)

Moon photos are strangely intimate: dust, visor reflections, careful movements. What makes certain frames feel “rarely seen” is how much they reveal in small details

the texture of the surface, the brightness of light, the way the human figure looks both heroic and slightly out of place. -

1972: The “Blue Marble”Earth as a single, shared home

The Blue Marble image took an abstract idea (“one planet”) and made it literal. Seen from space, borders vanish, and weather becomes the main character.

It’s one of those photos that quietly changes how people talk about responsibilitybecause you can’t look at it and pretend the planet is endless.

From Ash Clouds to Archive Rediscoveries (1974–2001)

-

1974: Nixon’s departureone frame, a whole political mood

Photos of resignation and transition often become “symbols” later, but in the moment they’re just documentation: a figure leaving, a helicopter waiting, a country

recalibrating. The power of this kind of image is how it compresses a complicated era into a single, unmistakable gesture. -

1980: Mount St. Helenswhen a camera (and film) survives the chaos

Some eruption images are official, dramatic, and widely published. Others feel oddly personallike frames recovered from a camera that took a beating and still

delivered proof. “Found film” photos hit differently because they feel like messages from the moment itself: damaged, real, and hard to ignore. -

1989: The Berlin Wall coming downhistory in motion

Photos from the Wall’s fall have a contagious energy: people climbing, chipping, celebrating, and reimagining the map in real time. The most compelling “rare”

frames are often the in-between onesfaces mid-laugh, hands mid-swingbecause they show freedom as an action, not a headline. -

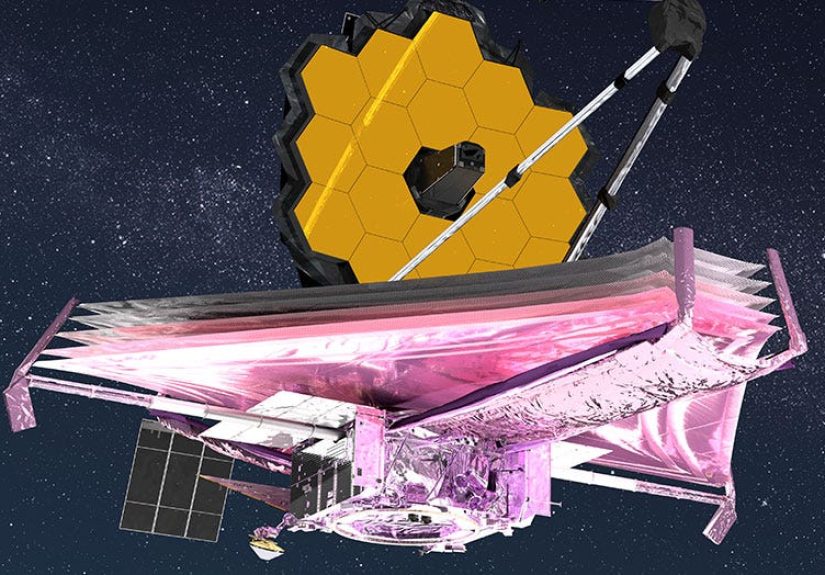

1995: The Hubble Deep Field“rarely seen” as a scientific achievement

Not all historic photographs show people. Some show perspective itself changing. The Hubble Deep Field stitched together many exposures of a tiny patch of sky and

revealed thousands of galaxies. It’s the kind of image that turns “space” from a background concept into a crowded neighborhood. -

2001: “Raising the Flag at Ground Zero”

This photo became a national emblem of resiliencethree firefighters lifting a flag amid devastation. Even without graphic detail, the image carries weight because

it records a human response to shock: to stand, to act, to claim a small moment of order when everything feels broken. -

2001: The lesser-known Ground Zero frame that complicates memory

Sometimes a “rarely seen” photo isn’t rare because it’s hiddenit’s rare because it doesn’t fit the simplified story we prefer. Alternate angles and less iconic

frames from the same day can feel quieter, grayer, and more human, reminding us that history isn’t a poster. It’s a lived day with many truths.

How to look at historical photographs without inventing a movie plot

Your brain wants to fill gaps. That’s normal. It’s also how myths are born. Here’s a simple way to stay curious and accurate:

- Start with what’s visible: clothing, tools, signage, weather, architecture, body language.

- Check the “why” of the photo: news, documentation, art, propaganda, personal album, government record.

- Notice who’s centered (and who’s missing): power often hides in composition.

- Ask what happened five minutes before and after: series photos and contact sheets are truth’s best friends.

- Respect the human subjects: especially when the moment involves trauma, injustice, or loss.

Experience: What it feels like to time-travel through rarely seen photos (and why you’ll get hooked)

The first time you scroll an archivereally scroll, not just “click one famous image and leave”something weird happens. You stop reading history and start

overhearing it. A photograph doesn’t announce itself with a neat thesis statement. It just sits there, quietly loaded with evidence, waiting for you to

notice the small stuff: a hand-written sign taped to a window, the scuff on a shoe, the way someone stands half-turned like they’re not sure the camera is allowed

to see them.

Then comes the zoom. The zoom is where the addiction starts. You lean in and suddenly the past becomes a collection of micro-stories. In a bridge construction photo,

you might spot lunch pails lined up like a little metal neighborhood. In an immigration portrait, you notice the fabric textures and realize this outfit wasn’t just

“clothing”it was a portable identity. In a protest image, you catch the tension between calm faces and chaotic surroundings, and you understand that courage can look

like composure, not fireworks.

What’s most surprising is how often “rare” photos feel familiar. Not because the events are the same, but because the emotions rhyme. People grin awkwardly in group

shots the same way they do now. Kids get bored in the background. Someone tries to look tough and accidentally looks like they’re auditioning for a serious

shampoo commercial. And in the middle of all that ordinary humanity, you realize you’ve been thinking about “history” like it was a different species. It isn’t.

There’s also a humbling part: learning how much you don’t know from one frame. A photo can show you a canal excavation, but not the full story of who got paid what,

who was protected, who got sick, who was celebrated, and who was erased. That doesn’t make the image useless. It makes it honest. It’s a doorway, not a conclusion.

The best experience of archive-diving is letting one photo lead you to questions you didn’t expectthen chasing those questions through captions, collections, and

context until the moment becomes three-dimensional.

And if you ever share these images (or write about them), the experience shifts again: you become a translator. Your job isn’t to “make it go viral.”

It’s to make it understandableaccurate dates, respectful language, and enough context that the people in the photo don’t get turned into props. Do that well, and

you’ll feel something rare in the internet age: the sense that you’re not just consuming the past. You’re taking care of it.

Conclusion

Rarely seen historical photographs aren’t just cool artifactsthey’re perspective machines. They remind us that the past was once somebody’s present, full of

uncertainty, effort, and ordinary days wrapped around extraordinary events. The more angles we preserve, the closer we get to truth that feels human, not packaged.

So the next time you see a famous moment, go looking for the “extra” frames. History is bigger than the poster shotand way more interesting.