Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Worst” Usually Means: High Cost, Low Value, and Too Many Traps

- Day 1: Coverage Isn’t Care (and “Insured” Isn’t Always “Protected”)

- Day 2: Price Tag Roulette and the “Surprise Bill” Era (Mostly) Afterward

- Day 3: Prior AuthorizationThe Fax Machine’s Final Boss Fight

- Day 4: Prescription DrugsSame Molecule, Different Universe

- Day 5: Primary Care Shortages and the Geography of “Good Luck”

- Day 6: ConsolidationWhen the Hospital Is Also the “Market”

- Day 7: The Human AftermathDebt, Delayed Care, and the Stress Tax

- So Why Is the U.S. System So Expensive?

- What Could Make the “Worst Week” Better?

- Experiences: A Composite Diary of “One Week in the Worst System” (About )

- Conclusion: The “Worst” Label Is Really a Warning Label

“Worst” is a strong word. It’s also the kind of word you use after spending a week trying to do something simplelike see a doctor, fill a prescription, or understand a billwhile the system responds by faxing you a riddle and charging you extra for the suspense.

Let’s be clear up front: the United States is not “the worst” on every possible measure. If you compare it to countries where hospitals are scarce, vaccines are hard to access, or basic sanitation is a challenge, the U.S. has world-class clinicians, cutting-edge technology, and some of the best specialized care on Earth. The “worst” label usually shows up in a narrower (and more embarrassing) category: among wealthy, high-income nations, the U.S. often delivers the worst valuespending the most while landing near the bottom on outcomes and affordability.

This article is a weeklong tour of that value problem: why health care costs so much, why coverage doesn’t always mean care, and why millions of people feel like they’re one surprise bill away from a stress-induced hobby of yelling at hold music. We’ll keep it real, keep it readable, andbecause we all deserve at least one small joykeep it a little fun.

What “Worst” Usually Means: High Cost, Low Value, and Too Many Traps

When researchers rank health systems, they’re rarely judging who has the fanciest surgical robot. They’re looking at a bundle of things that matter to normal humans: access, affordability, equity, outcomes, administrative efficiency, and the experience of getting care.

On many international scorecards focused on high-income peers, the United States ends up in an awkward position: best-in-class spending (meaning: extremely high) paired with mediocre or poor health outcomes. In plain English: we pay luxury-car money and sometimes get “Check Engine” results.

The spending part is not subtle

National health spending in the U.S. is measured in trillions, and it keeps climbing. Per-person spending is also unusually high compared with other wealthy countries, even before you add the “extra fees” of time, stress, and paperwork-induced eye twitching. The U.S. also devotes a larger share of its economy to health care than peer nations.

The outcomes part is the gut punch

Despite extraordinary clinical capability, overall health outcomes (like life expectancy) lag behind what you’d expect given the price tag. Some years improve, some years worsen, but the broader pattern is persistent: the U.S. doesn’t reliably convert its spending into population-level health the way other high-income systems do.

The experience part is the plot twist

Even if you have insurance, you can still be underinsured (high deductibles and copays), stuck in narrow networks, delayed by prior authorization, or billed incorrectly. And if you don’t have insuranceor you lose it mid-yearaccess becomes a game of “how bad does this have to get before I go to urgent care?”

Day 1: Coverage Isn’t Care (and “Insured” Isn’t Always “Protected”)

Welcome to Day 1, where you learn a crucial phrase in the U.S. health care system: “That depends.”

Do you have insurance? That depends on your job, your age, your income, your state, your paperwork timing, and whether the universe decided to test your character development this week.

Nationally, most people do have health coverage. But millions remain uninsured in any given year, and many more experience coverage gaps. Even among the insured, a large chunk is effectively underinsuredmeaning they technically have a plan, but the out-of-pocket costs are high enough to discourage care.

Networks: the velvet rope you didn’t know you were approaching

Insurance networks are supposed to control costs by steering patients to contracted providers. In practice, networks can feel like a bouncer deciding whether you’re allowed into the club. You can have a perfectly good plan and still discover:

- Your preferred doctor is “out of network” (or “in network, but only on Tuesdays during a solar eclipse”).

- The hospital is in network, but the anesthesiologist is not.

- The clinic is covered, but the lab they use is not.

The result is a system where you spend time doing detective work before you can do the thing you actually want: get medical care.

Day 2: Price Tag Roulette and the “Surprise Bill” Era (Mostly) Afterward

On Day 2, you receive a bill that looks like it was generated by a toddler with access to a calculator and a grudge.

Historically, “surprise medical billing” happened when patientsoften during emergencieswere treated by out-of-network providers without realizing it. The No Surprises Act was created to protect patients from many of these scenarios, especially for emergency care and certain services at in-network facilities.

That’s real progress. But it’s not a magic wand. Patients can still face:

- High deductibles and coinsurance (the “you pay a percentage” feature that always picks a dramatic percentage).

- Billing errors, duplicate charges, and confusing itemized statements.

- Costs for services not covered, not authorized, or not considered “medically necessary” by the insurer.

- Out-of-network care in situations not fully captured by protections, especially when care is fragmented across providers.

Why prices are so high in the first place

In many countries, prices are set or tightly negotiated. In the U.S., prices often emerge from negotiations among hospitals, health systems, insurers, and middlemen. That might sound like a market. In reality, it can look like a market where the biggest players combine, gain leverage, and raise priceswhile consumers shop blindfolded because they can’t get a clear price in advance.

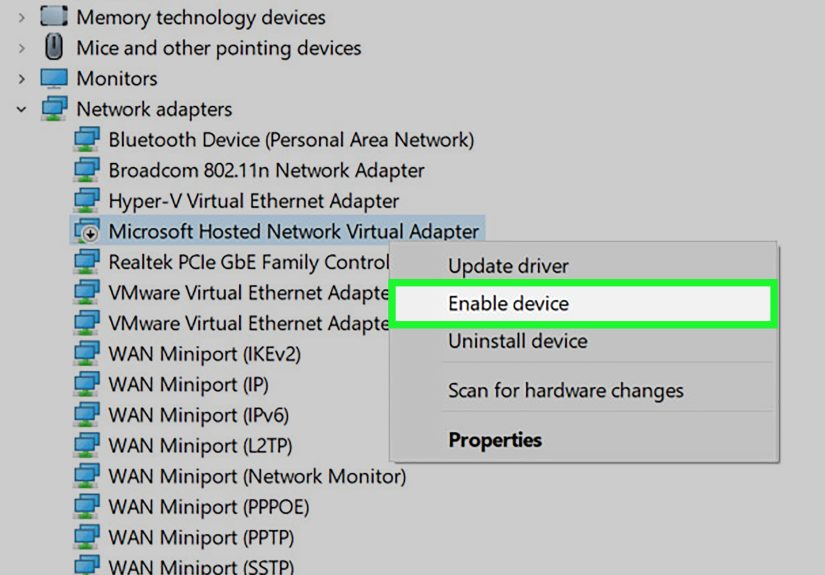

Day 3: Prior AuthorizationThe Fax Machine’s Final Boss Fight

Day 3 is when your doctor says, “I want you to get this test,” and your insurer replies, “Prove it.”

Prior authorization requires clinicians to get approval before certain medications, imaging, procedures, or services will be covered. In theory, it prevents unnecessary care. In practice, it often creates delays, extra appointments, and administrative work that chews up time for doctors and staff.

Physician surveys routinely find that prior authorization:

- Delays care for most practices.

- Increases administrative burden, sometimes consuming hours each week per physician.

- Leads to treatment abandonment when patients can’t wait or can’t fight through the process.

- Is associated with reported harm when delays worsen conditions.

The emotional experience is strangely universal: you can be a calm person with a reasonable email signature, and prior authorization will still make you consider changing your signature to “Sent from my therapist’s waiting room.”

Day 4: Prescription DrugsSame Molecule, Different Universe

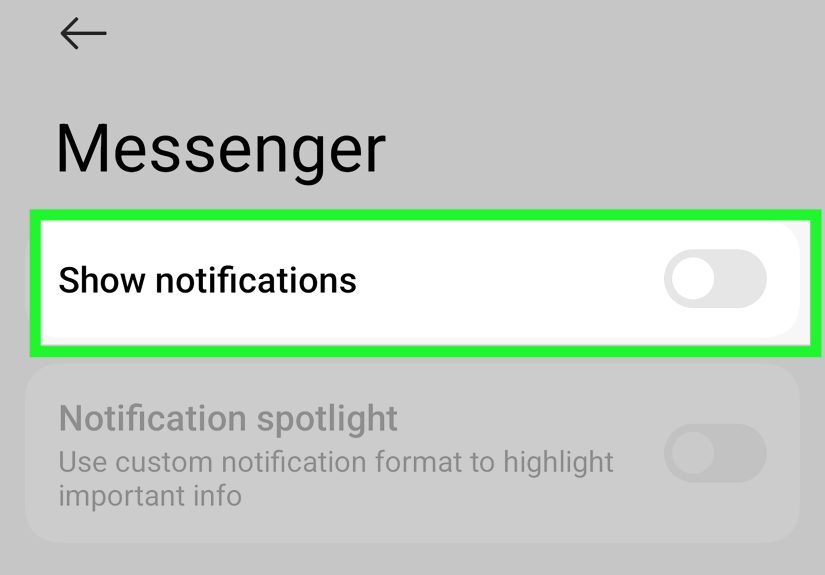

Day 4 is pharmacy day. You learn your medication is “covered,” which is insurance language for “a surprise is on the way.”

U.S. prescription drug pricesespecially for brand-name drugsare consistently higher than prices in other high-income countries. Comparative analyses find that brand drug prices in the U.S. can be multiple times higher than in peer nations, even after accounting for rebates and discounts that occur behind the scenes.

Why it matters in real life

High drug prices translate into:

- Patients rationing medications or skipping refills.

- Higher premiums and higher employer costs.

- More financial stress, especially for chronic conditions that require ongoing treatment.

Yes, the U.S. also leads in launching new drugs and funding innovation. But “innovation” feels less inspiring when your options are “pay $900” or “hope for the best.” A system can reward discovery without turning the checkout counter into a second diagnosis.

Day 5: Primary Care Shortages and the Geography of “Good Luck”

Day 5 is when you try to schedule a primary care appointment and discover the earliest availability is sometime after your next birthday.

Primary care is the front door of health care: prevention, chronic disease management, and early treatment. When primary care is scarce, people often end up in urgent care or emergency rooms for issues that should have been handled earlier and cheaper.

Many areas of the U.S. are officially designated as having shortages of primary care professionals. Rural communities, in particular, face compounding barriers: fewer clinicians, longer travel distances, and limited after-hours care. The end result is a system that can be clinically advanced and still practically inaccessible depending on your ZIP code.

Why shortages amplify “worst system” feelings

Even a well-designed insurance plan can’t conjure a doctor who doesn’t exist nearby. When the supply is thin, the burden shifts to patients: more travel, more time off work, more delays, and more expensive care later.

Day 6: ConsolidationWhen the Hospital Is Also the “Market”

Day 6 is when you realize your local hospital system owns:

- the hospital,

- the urgent care,

- the imaging center,

- the physician group,

- and possibly the coffee shop where you cry into a muffin after reading your Explanation of Benefits.

Provider consolidationhospital mergers, health system acquisitions of practices, and large integrated networkscan reduce competition. When a system becomes “the only game in town,” it can negotiate higher prices with private insurers. Policy analyses warn that consolidation can raise prices in private insurance markets and push overall costs upward without reliably improving quality.

Consolidation also changes the patient experience. You may have fewer independent options, fewer alternative clinics, and less price pressure. In a normal market, consumers can choose cheaper alternatives. In health care, you often choose based on emergency, proximity, or whatever your insurance network allows. That’s not a market; that’s a maze with a velvet rope.

Day 7: The Human AftermathDebt, Delayed Care, and the Stress Tax

By Day 7, you’re not just tired. You’re financially and emotionally taxed by the process of getting care. And that stress is not evenly distributed.

Medical debt: the uniquely American sequel nobody asked for

Medical debt is common enough to be considered a structural feature of U.S. health care. Surveys repeatedly find that a substantial share of adults carry health care-related debt, often from one-time emergencies, ongoing chronic conditions, or surprise out-of-pocket expenses even when insured.

Debt can lead to painful trade-offs: delaying care, skipping prescriptions, cutting essentials, or avoiding follow-up visits. It also increases stresssomething you can’t bill insurance for, but your body will still pay for.

“I’ll just wait it out” becomes a health strategy

Cost-related delays happen across the population, but they’re particularly common among uninsured adults and households with high deductibles. People postpone doctor visits, tests, or treatment until symptoms become unignorableat which point the care is often more intense and more expensive.

Administrative waste: the invisible line item

It’s not just the clinical care that costs money. The U.S. system’s complexitymultiple payers, different rules, different benefits, repeated paperworkcreates administrative overhead for providers and insurers alike. Patients feel it as time and confusion; the economy feels it as dollars that could have gone to actual care.

So Why Is the U.S. System So Expensive?

If you had to summarize the cost problem in one sentence, it’s this: the U.S. doesn’t necessarily use dramatically more health care than peersit often pays higher prices for the care it uses, and it carries heavier administrative complexity along the way.

Several drivers show up repeatedly in research and policy discussions:

- Higher prices for hospital services, physician services, and many drugs.

- Market power from consolidation among hospitals and health systems.

- Insurance design that shifts costs to patients through deductibles and coinsurance.

- Fragmentation that creates administrative overhead and care gaps.

- Underinvestment in primary care, which makes downstream costs worse.

And hanging over all of it is scale: when national spending reaches trillions and keeps growing, even “small” inefficiencies become massive.

What Could Make the “Worst Week” Better?

No single reform fixes everything. But many proposals cluster around a few practical goalsthings that would make a real difference in a real week of seeking care.

Make care truly affordable, not just “covered”

That means addressing high deductibles, unpredictable coinsurance, and benefit designs that punish people for getting sick. Coverage should reduce risk, not repackage it.

Reduce administrative friction

Simplify billing and standardize insurance rules where possible. Modernize prior authorization with real-time decisions for routine services, clear clinical criteria, and continuity protections when people switch plans.

Strengthen primary care capacity

Increase access to primary careespecially in shortage areasso people can get preventive care and chronic disease management without resorting to the emergency room.

Address pricing power and transparency

Encourage competition where it can exist, regulate where it can’t, and make pricing information meaningful. “Transparent” shouldn’t mean “posted somewhere in a file named FINAL_FINAL_3.”

Lower prescription drug costs

Other high-income countries manage to pay less for many brand-name drugs while maintaining access. The U.S. can pursue smarter negotiation, faster generic and biosimilar competition, and benefit designs that don’t turn patients into collateral damage.

Experiences: A Composite Diary of “One Week in the Worst System” (About )

Monday: You wake up with a sharp pain that refuses to be ignored. You call your primary care office. The earliest appointment is three weeks away, but they can squeeze you in with a nurse practitionerif you can arrive during a 45-minute window that overlaps perfectly with your job’s “important meeting of the year.” You pick the appointment anyway because pain is persuasive.

Tuesday: The visit goes well. The clinician listens, examines you, and recommends imaging “just to be safe.” Then you meet the second clinician of the day: your insurance plan. The imaging center is in network, but the radiologist group might not be. The scheduler can’t confirm. Your insurer’s directory says the radiologist is “participating,” which is comforting until you learn the directory was last updated sometime during the Renaissance.

Wednesday: Prior authorization enters the chat. The test isn’t approved yet. The clinic staff submits paperwork, but the insurer wants more documentation. The staff tries again. You try to stay calm and remind yourself that stress is bad for healing, which is ironic because the entire process appears designed to cultivate stress like a hobby garden.

Thursday: You go to the pharmacy for a medication the clinician prescribed to help with symptoms. The pharmacist says, “It’s covered, but your copay is high because you haven’t met your deductible.” You learn your deductible is so tall it needs its own zip code. You consider paying cash, but the cash price is also impressivein the way a thunderstorm is impressive when it’s headed directly toward your picnic.

Friday: The imaging is finally approved. You schedule it. The earliest slot is in two weeks, unless you drive 45 minutes to a different location. You drive. In the waiting room, you notice everyone looks like they’ve been here beforenot just in this building, but in this same storyline.

Saturday: An Explanation of Benefits arrives. It is not a bill, but it reads like a bill written by an escape-room designer. It lists “allowed amounts,” “patient responsibility,” and codes that look like they belong in a spy movie. You don’t know what you owe yet, but you know you will be thinking about it at 2 a.m.

Sunday: You tally the week: time off work, hours on the phone, anxiety spikes, and a growing folder of documents titled “HEALTHCARE (DO NOT OPEN IF YOU’RE TRYING TO HAVE A NICE DAY).” Your care itself was competent and compassionate. The system surrounding it was not. And that’s the point: in the U.S., the worst part of health care is often not the medicine. It’s the maze you must survive to reach it.

Conclusion: The “Worst” Label Is Really a Warning Label

Calling the U.S. “the worst health care system in the world” is rhetoricalbut it points to something real: for a wealthy nation, the U.S. system often delivers unusually poor value. Costs are high, outcomes lag peers, and the path to care is cluttered with administrative traps that burn time, money, and trust.

The good news is that none of these problems are mysterious. High prices, fragmented coverage, prior authorization burdens, provider consolidation, primary care shortages, and medical debt are identifiableand therefore fixable. The hard part isn’t diagnosing the system. The hard part is choosing, collectively, to treat it.