Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “higher risk” actually means (and why it often sounds scarier than it is)

- Health conditions where taller height is often linked to higher risk

- Health conditions where shorter height is often linked to higher risk

- So… why would height affect disease risk at all?

- What you should do with this information (without spiraling)

- Real-World Experiences: what people often notice (and what tends to help)

- Conclusion

The title is in Spanish, but the question is universal: does being tall (or short) change your odds of getting certain diseases?

If you’ve ever had someone say, “Wow, you’re talldo you play basketball?” you’ve met the human instinct to turn height into a personality.

Science is a little more polite: it treats height as a biological clue, not a destiny.

Here’s the honest answer: height can be linked to disease risksometimes higher, sometimes lowerdepending on the condition.

But the headline you should remember is this: height is a background factor. Your day-to-day choices (sleep, movement, food, smoking, preventive care)

usually do far more heavy lifting than your genes did when they built you.

What “higher risk” actually means (and why it often sounds scarier than it is)

When researchers say “taller people have a higher risk,” they usually mean relative risk, not “this will happen to you.”

A relative increase can sound dramatic even when the absolute risk stays small. If something rare becomes “30% more likely,” it can still be rare.

So yes, height matters in statisticsbut it’s not a prophecy.

Three quick reality checks before we talk diseases

- Height is partly a record of early life: genetics, childhood nutrition, illness, and environment all shape adult height.

- Associations aren’t always causation: some studies show correlation; others use genetic methods (like Mendelian randomization) to get closer to causal links.

- Risk is a team sport: height interacts with weight, age, activity, hormones, and family historyso it rarely acts alone.

Health conditions where taller height is often linked to higher risk

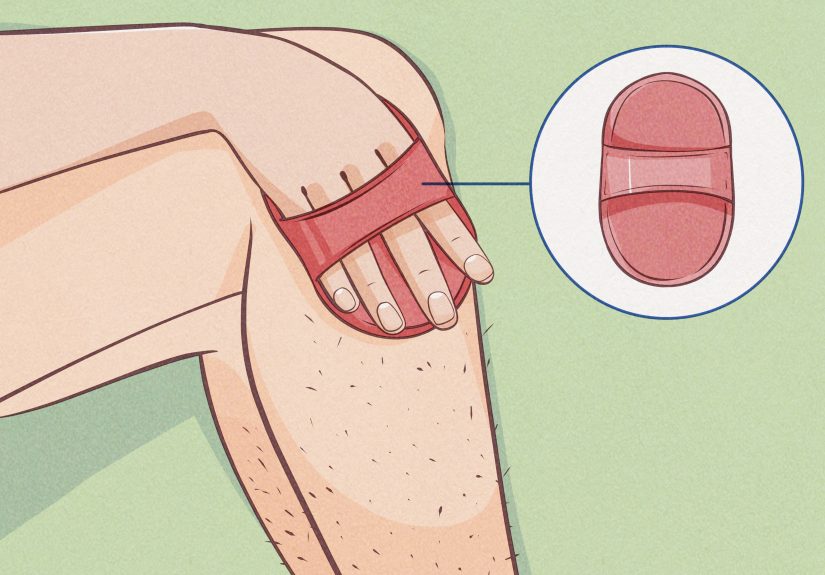

1) Blood clots (VTE: DVT and pulmonary embolism)

One of the clearest, most consistent findings: taller adults tend to have a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE),

which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

Large studies using both traditional and genetic approaches have found that VTE risk rises as height rises.

Why would height matter? Think plumbing plus gravity. Longer veins can mean more surface area and more valvesand hydrostatic pressure may be higher in the leg veins.

That can set the stage for clot formation, especially when you stack other risks on top: long travel, surgery, immobility, smoking, certain medications, pregnancy, or cancer.

Practical takeaway (tall or not): if you’re doing a long flight or road trip, move your legs, stand up regularly, hydrate, and don’t ignore sudden swelling or pain.

Your calves are basically your “backup heart” for pushing blood upwardlet them do their job.

2) Atrial fibrillation (AFib)

Multiple studiesespecially those using genetic datasuggest taller height is associated with higher risk of atrial fibrillation,

a common heart rhythm problem that can raise the risk of stroke.

The “why” is still being mapped, but body size can correlate with heart chamber size, and electrical timing can be influenced by structural differences.

Don’t panic if you’re tall and your smartwatch occasionally calls you “interesting.” Most palpitations are not AFib.

But if you have symptoms like persistent fluttering, dizziness, shortness of breath, or episodes that keep recurring, it’s worth a real medical evaluation.

3) Varicose veins (and downstream leg issues)

Tall people hear “How’s the weather up there?” a lot. Your leg veins might also feel like they’re living at a higher altitude.

Research including genetic analyses suggests greater height increases the likelihood of varicose veins.

Varicose veins are common and often more annoying than dangerous, but they can come with aching, swelling, andin some casesskin changes or ulcers.

If you’re tall and you notice heaviness, swelling, or visible twisted veins, that’s not vanity; that’s venous circulation doing a dramatic reading.

Compression socks, movement, weight management, and medical guidance can helpespecially if symptoms progress.

4) Certain cancers (a modest increase, spread across many types)

Many large population studies have found a pattern: taller adults have a slightly higher risk of several cancers (not all, and not equally).

The increase is typically modest, but it shows up repeatedly across different groups and methods.

The most intuitive explanation is also the simplest: more cells, more opportunities for something to go wrong over a lifetime.

There are also biological pathways tied to growthlike hormones and growth factors involved in childhood developmentthat may influence cancer risk later.

Importantly, height is not a “cause” you can change, and it doesn’t replace the big hitters: tobacco exposure, alcohol, UV exposure, obesity, infections, and screening behavior.

Translation into real life: being tall is not a cancer sentence. It’s more like a small nudge in a risk calculatorone that matters far less than

whether you smoke, avoid sunburn, maintain a healthy weight, and follow evidence-based screening schedules.

5) Musculoskeletal strain (back pain and possibly more severe cases)

Tall bodies can be wonderfuluntil they meet a world designed around “average.”

Some research suggests taller height may be linked to higher odds of severe low back problems (including surgical outcomes in certain cohorts).

Mechanisms may include mechanical loading, disc geometry, andvery realisticallytall people constantly folding themselves into chairs like origami.

This doesn’t mean “tall = doomed back.” It means tall people may benefit disproportionately from:

core strength, hip mobility, ergonomic work setups, and smart lifting habits.

Health conditions where shorter height is often linked to higher risk

1) Coronary heart disease (CHD)

Here’s where the story flips: many studies have found that shorter adult height is associated with higher risk of coronary heart disease

and cardiovascular mortality. This relationship is complicated, and it likely reflects a mix of genetics, early-life nutrition and illness, and cardiometabolic factors.

Some modern analyses using genetic approaches suggest taller height may slightly lower the odds of CHD,

potentially through pathways related to blood pressure and cholesterol. In plain English: height can correlate with cardiovascular architecture and lifelong biology,

but it’s not a “free pass.” You still need the fundamentals: blood pressure control, lipid management, physical activity, and not smoking.

2) Metabolic and microvascular complications (context matters)

Height is also tied to early development, and early development is tied to metabolic health.

Some studies have reported links between shorter adult stature and higher rates of certain diabetes complications in specific populations.

This doesn’t mean short height causes complications; it suggests that the same life-course factors influencing growth may also influence long-term metabolic resilience.

So… why would height affect disease risk at all?

Mechanism #1: The “more tissue” concept

Bigger body frames can mean more cells and sometimes larger organs.

If cancer risk is partly a numbers game over decades, that may help explain why taller height shows up as a small risk factor across multiple cancer types.

Mechanism #2: Growth pathways (hormones and growth factors)

Adult height is the final score of childhood growth signals.

Growth hormone and related growth factors are crucial for normal development, and extreme states (too much growth hormone) illustrate how those pathways can affect the body.

In the everyday range, these growth-related systems may still influence long-term risk profiles in subtle ways.

Mechanism #3: Circulation physics (especially in the legs)

With greater height, you often get longer venous pathways.

That can influence venous pressure and pooling, which may help explain links with varicose veins and blood clotsespecially when combined with inactivity.

Mechanism #4: Early-life environment and “biological memory”

Height captures early-life conditions: nutrition, infections, stress, socioeconomic factors, and more.

Those same exposures can influence cardiovascular and metabolic risk later.

That’s one reason researchers are careful: height may be a marker for a whole bundle of life-course inputs.

What you should do with this information (without spiraling)

If you’re tall

- Take circulation seriously during long travel: walk, stretch calves/ankles, hydrate, and consider compression socks if you’re high-risk.

- Know clot warning signs: sudden one-sided leg swelling, pain, warmth, redness, shortness of breath, or chest pain need urgent attention.

- Respect your back: ergonomics, strength training, and mobility work are not “optional accessories.”

- Don’t skip screening: follow age-appropriate cancer screening guidanceheight is not the main driver, but prevention still matters.

If you’re shorter

- Be proactive with heart health: blood pressure, cholesterol, glucose, and fitness matter enormously.

- Lean into the controllables: diet quality, movement, sleep, and tobacco avoidance outweigh height in most risk calculators.

- Track family history: genetics can amplify risk far more than a few inches ever could.

If you’re anywhere in the middle

Congratulationsyou’re statistically normal, and you still have to eat vegetables.

(Sorry. I don’t make the rules. Actually, public health does.)

Real-World Experiences: what people often notice (and what tends to help)

This topic isn’t just charts and hazard ratios; it shows up in everyday life in surprisingly consistent ways. Here are experiences people commonly report,

pulled from patterns clinicians hear and what the research would predicttold in plain English, with the kind of practical details that never make it into a headline.

The tall-traveler leg saga

Many tall people learn about circulation the same way they learn about airplane seat geometry: abruptly.

A long flight lands, you stand up, and your legs feel like they’ve been storing extra fluid as a hobby.

Most of the time it’s mild swelling that improves with walkingbut the “aha” moment is realizing that immobility is the villain, not height alone.

People who do best tend to build a routine: aisle walks every hour, calf raises while seated, water over booze, and loose clothing that doesn’t turn your knees into tourniquets.

The “Is this varicose veins or just… legs?” question

A common experience is noticing new bulging veins after periods of standingteaching, retail work, long events, or just living life upright.

The helpful shift is moving from cosmetic worry to symptom tracking:

aching at day’s end, heaviness, ankle swelling, skin itching or discoloration.

People often feel better once they treat it like what it is: a circulation issue.

Compression socks get an unfair reputation as “grandparent fashion,” but plenty of tall adults become true believers after one week of wearing them at work.

Back pain and the “world is not built for me” effect

Tall people frequently describe a slow grind of small mismatches: sinks too low, desks too short, car headrests placed for someone else’s spine,

and chairs that turn long femurs into a geometry problem.

Over time, that can mean neck strain, tight hip flexors, and lower back flare-ups.

The most consistent “wins” people mention are boringbut effective:

raising screens to eye level, using lumbar support, strength training that targets glutes and core, and taking micro-breaks instead of marinating in one posture for eight hours.

It’s not glamorous. It’s also not optional if you want your back to stop filing formal complaints.

AFib anxiety in the smartwatch era

Taller adults sometimes get spooked by heart-rhythm notifications or occasional palpitationsespecially if they’ve heard about the height-AFib link.

The real-world pattern is that reassurance comes from getting the basics checked:

blood pressure, sleep quality (including sleep apnea risk), alcohol intake, and stimulant use.

People also report that learning AFib symptomspersistent irregular heartbeat, fatigue, dizziness, shortness of breathhelps them respond appropriately rather than catastrophize.

In other words: knowledge turns “What if?” into “Here’s what I’ll do if it happens.”

Shorter adults and “heart health vigilance”

Shorter adults who learn about the height–coronary heart disease association often react in one of two ways:

(1) anxiety, or (2) motivation. The best outcomes tend to come from the second.

Many people describe a sense of control when they focus on measurable markers:

improving walking endurance, lowering blood pressure, getting LDL cholesterol to target, and building consistent sleep.

A recurring theme is that the “height factor” becomes less scary once it’s placed correctlybehind the much larger levers of lifestyle and preventive care.

The shared lesson across heights is almost annoyingly consistent:

height may tilt the table, but habits set the game pieces.

If you want something actionable from this entire discussion, it’s this:

know your numbers (BP, lipids, glucose), keep moving, don’t smoke, and show up for preventive care.

Your future self will thank youwhether they’re reaching the top shelf or asking someone else to do it.

Conclusion

Can height increase the risk of diseases? Sometimesdepending on the disease.

Taller height is often linked with higher risk of conditions like blood clots, atrial fibrillation, varicose veins, and several cancers,

while shorter height is often linked with higher risk of coronary heart disease.

But the biggest message is not “be worried”it’s “be smart.”

Height is one variable you can’t change. The good news is that the most powerful risk reducers are the ones you can change:

movement, nutrition, sleep, smoking status, weight management, and routine screening.

Use height as a nudge toward better preventionnot as a label.