Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why the Internet Can’t Look Away From Client-Sketch Comparisons

- What a Client Sketch Really Is (Hint: It’s Not an Art Test)

- How Artists Turn “This Little Doodle” Into “This Belongs in a Frame”

- Why Artists Love Client Sketches (Even the Chaotic Ones)

- Why Viewers Love the Before-and-After So Much

- The Business Side: Sketch Approval, Revisions, and “What Are We Actually Paying For?”

- How Clients Can Get Better Results (Without Becoming an Art Director Villain)

- How Artists Can Set Up Commissions for “Happy Comparison Posts”

- Five Mini “Client Sketch vs Delivered” Scenarios (Text Edition)

- So… Should Clients Always Send Sketches?

- Conclusion: The Comparison Isn’t the PointThe Collaboration Is

- Experience Corner: What Artists and Clients Commonly Learn the Hard Way (500+ Words)

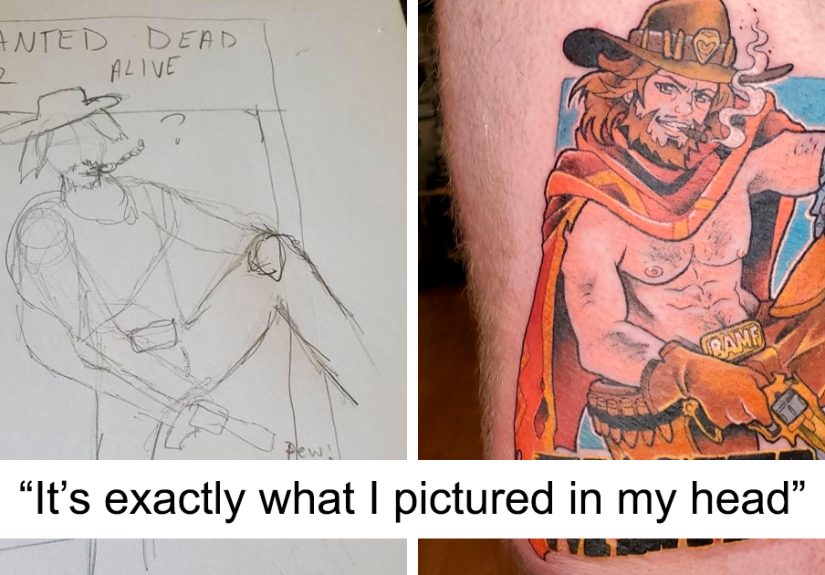

There are few things on the internet more comforting than watching chaos turn into competence. Not “I organized my pantry” comfort.

I’m talking full-blown magic: a client sends an artist a sketch that looks like it was drawn in a moving car (because it probably was),

and the artist delivers a polished illustration that makes everyone in the comments go, “WAIT… that came from that?”

These side-by-side postsclient sketch vs. final delivered arthave become a mini-genre online. They’re funny, satisfying, and (sneakily)

educational. You’re not just seeing a before-and-after. You’re watching translation happen: vague ideas turning into visual decisions,

stick figures becoming anatomy, “make it pop” becoming lighting, color, and composition.

In this article, we’ll unpack why people love these comparisons so much, what artists are really doing between “rough idea” and “final render,”

and how both clients and creatives can make commissions smoother (with fewer “can you just…” moments and more “wow, you nailed it” endings).

Why the Internet Can’t Look Away From Client-Sketch Comparisons

The format hits a sweet spot: it’s a transformation story you can understand in half a second. Left image: a doodle with arrows, notes,

and a heroic amount of optimism. Right image: a professional piece that looks like it belongs on a book cover, album art, a brand campaign,

or the wallpaper on someone’s “I swear I’m productive” laptop.

It also scratches a very human itch: we like seeing “how the sausage is made” as long as the sausage ends up delicious.

Before-and-after content works because the contrast is obvious and the payoff is immediate. In art, that payoff includes surprise:

people underestimate how much information can be extracted from even a messy sketch.

It’s Not Just a Glow-UpIt’s Proof of Skill

A good comparison shows the hidden labor: problem-solving, visual storytelling, and technical chops. The audience gets a quick lesson in

what “art” actually involves beyond “being good at drawing.” Things like:

- Clarifying intent: What is the client trying to say with this image?

- Choosing emphasis: What matters mostemotion, humor, brand clarity, or realism?

- Composing a readable scene: Where do your eyes go first, and why?

- Controlling style: Cute, cinematic, gritty, minimal, hyper-detailedeach requires different decisions.

- Finishing: Color harmony, lighting, texture, typography (sometimes), export settings, and delivery formats.

What a Client Sketch Really Is (Hint: It’s Not an Art Test)

Here’s the big misunderstanding: clients sometimes avoid sketching because they think the artist will judge them.

Artists, meanwhile, are basically begging for any sketch at allbecause it’s not a performance. It’s a map.

A client sketch is most useful when it answers the question: “What do you mean?” Not in a philosophical way.

In a “when you say ‘two characters standing together,’ do you mean shoulder-to-shoulder like a buddy movie poster,

or facing each other like a rom-com?” kind of way.

What to Include in a Client Sketch (Even If You Draw Like a Potato)

- Basic layout: Where are the main elements placed? Centered? Off to the side? Close-up? Wide shot?

- Key props or features: “This character must have the scar,” “this dog must be a corgi,” “the logo must be readable.”

- Emotion and vibe: Happy, eerie, cozy, chaotic, heroic, sarcasticyes, sarcasm is a vibe.

- Labels and arrows: The universal language of “I can’t draw it, but I can explain it.”

- Reference images: Not to copy, but to clarify style, lighting, clothing, era, or anatomy.

A sketch can be stick figures as long as it communicates priorities. If your drawing looks like a crime-scene diagram, congratulations:

you’re doing it right.

How Artists Turn “This Little Doodle” Into “This Belongs in a Frame”

Between client sketch and final art, there’s usually a repeatable workflowbecause professionals don’t just “wing it” and pray.

The exact steps depend on the medium (digital illustration, painting, tattoo design, logo work, character design), but the logic is similar:

reduce risk early, refine later.

A Typical Commission Workflow

- Intake + brief: The artist gathers details: subject, purpose, style, deadline, size, usage rights, budget, and references.

- Rough thumbnails: Tiny quick compositions exploring options. This is where big changes are cheap.

- Sketch/rough approval: A clearer draft is sent for feedback so everyone agrees on direction before rendering begins.

- Line art or refined sketch: Shapes get cleaner, anatomy tightens up, perspective stops acting like it’s on a trampoline.

- Color comps (often): Small color tests to lock mood, lighting, and palette.

- Final render: Detail, texture, lighting, polish, and any requested deliverables (backgrounds, variations, print files).

- Delivery: Final files are exported correctly (dimensions, color profile, resolution) and sent with any usage notes.

That “sketch approval” step is the superstar behind most successful client-artist collaborations. It’s the moment where

“I thought you meant…” gets caught before anyone spends eight hours painting a sunset the client never wanted.

Why Artists Love Client Sketches (Even the Chaotic Ones)

From the artist’s perspective, a client sketch is a shortcut to clarity. It reveals what the client is picturing, not just what they’re saying.

And in creative work, those two things can be as different as “a simple logo” and “a logo with a dragon, a compass, three fonts, and the concept of destiny.”

Client Sketches Help Artists Spot Hidden Requirements

- Scale expectations: Is this a portrait, a scene, or a whole illustrated world?

- Focus: Are we highlighting a character, a relationship, a product, or a joke?

- Story beats: What’s the momentaction, reaction, or aftermath?

- Non-negotiables: The one detail that matters most (and must not “accidentally” vanish).

Even a rough sketch can prevent the most common commission disaster: both parties thinking they agreed, but visualizing two completely different things.

Why Viewers Love the Before-and-After So Much

Audiences aren’t just rubbernecking the “bad sketch” (although the internet does enjoy a harmless giggle).

They’re reacting to three deeper satisfactions:

1) The Transformation Narrative

Before-and-after content is basically a story with a beginning and a satisfying ending. In art, the “after” doesn’t just look better;

it looks intentional. That shiftfrom messy possibility to confident clarityfeels rewarding.

2) The Brain Loves Increased Clarity

When you see a sketch, your brain works harder to interpret it. When you see the final, comprehension becomes easier.

That jump in clarity can feel pleasurablelike solving a tiny visual puzzle and getting a reward.

3) It Builds Respect for the Process

People come away thinking, “Oh… this isn’t just drawing. It’s design, decisions, craft, and patience.”

The comparison makes the invisible visible: line confidence, color control, lighting, texture, and composition.

The Business Side: Sketch Approval, Revisions, and “What Are We Actually Paying For?”

The most wholesome comparisons often hide the most important truth: good commissions are structured.

Not stiff. Not corporate. Just clear.

Revisions: The Difference Between “Fixing” and “Changing the Assignment”

Most professional agreements distinguish between:

- Revisions within scope: Adjusting details that align with the approved direction (e.g., tweak expression, adjust colors).

- New direction changes: “Actually, can we make it a different pose, different outfit, different background, and also a different art style?”

That’s why sketch approval matters: once a direction is approved, big changes usually cost more time (and often more money).

Deposits and Payment Milestones

Many artists use deposits and milestone payments to protect their time and keep projects moving.

A common structure is partial payment upfront, with the remainder due at final delivery (or split across stages like sketch approval and final).

Rights and Usage: Personal Use vs. Commercial Use

Another frequent surprise: buying a commission doesn’t automatically mean buying all rights in every case.

In many situations, the artist retains copyright unless rights are specifically transferred or licensed.

Commercial usage (branding, merch, ads, packaging) often costs more because it has broader value.

Translation: if you’re commissioning a portrait for your living room, that’s different from commissioning artwork for a product you’ll sell.

The art might look similar, but the usage is not.

How Clients Can Get Better Results (Without Becoming an Art Director Villain)

Want the “people love seeing the comparison” outcome? Here’s the client-side playbook.

Write a Brief That Doesn’t Make the Artist Play Detective

A great brief is short, specific, and prioritizes what matters. Use this checklist:

- Purpose: What is this for (gift, profile image, book cover, brand illustration, tattoo concept)?

- Subject: Who/what is included (characters, pets, objects)?

- Must-haves: 3–5 non-negotiables (pose, key prop, text, colors, symbols).

- Style references: 2–6 images showing the vibe (not to copyjust to guide).

- Deadline: The real deadline (and any flexibility).

- Usage: Personal only, or commercial use?

Do This One Thing and Every Artist Will Secretly Thank You

Say what you like about the reference. Don’t just paste images. Explain: “I like the lighting,” “I like the line weight,”

“I like the color palette,” or “I like that it feels playful and not hyper-realistic.”

Give Feedback Like a Pro

- Be concrete: “Make the character look more confident” becomes “raise the chin slightly, soften the brows, widen the stance.”

- Rank priorities: “If only one thing changes, I want the facial expression adjusted.”

- Don’t rewrite the brief midstream: If you must change direction, acknowledge it and expect timeline/cost changes.

How Artists Can Set Up Commissions for “Happy Comparison Posts”

Artists already know the work is hard. The trick is preventing preventable pain.

Ask the Questions Clients Don’t Realize Matter

- “What’s the main emotion you want viewers to feel?”

- “What’s the one detail that must be correct?”

- “Are you flexible on pose/background/style?”

- “Where will this be used (personal vs. commercial)?”

Define the Revision Policy in Plain English

“Two rounds of revisions at the sketch stage, one minor adjustment round at final” is clearer than

“revisions included” (which is basically an invitation for revision chaos to move in and start paying rent).

Use Checkpoints to Avoid the Revision Spiral

A structured process protects both sides: client feels heard early, artist avoids repainting an entire piece because

someone suddenly discovered they prefer sunsets to moonlight.

Five Mini “Client Sketch vs Delivered” Scenarios (Text Edition)

Since we’re not embedding images here, let’s recreate the vibe with realistic examples of how these comparisons usually look.

If you’ve spent any time in commission land, at least one will feel uncomfortably familiar (in a funny way).

1) The “Stick Figure Romance”

Client sketch: Two stick figures. One heart floating above them. A note: “Make it cute.”

Delivered art: A warm, soft-lit illustration of two characters leaning into each other under string lights, subtle blush,

cozy sweaters, and a background that whispers “this is their favorite coffee shop.”

2) The “My Dog, But Heroic” Request

Client sketch: A rectangle labeled “dog,” wearing a cape. The cape is also a rectangle.

Delivered art: A dramatic, cinematic portrait of a real dog with accurate markings, cape flowing, rim lighting, and a determined expression

that says, “I will protect this household from vacuum cleaners.”

3) The “Logo Concept… Sort Of”

Client sketch: A scribble that might be a leaf or might be a jellyfish. Text: “Modern. Premium. Not boring.”

Delivered art: A clean, scalable logo mark with balanced geometry, a refined type pairing, and brand colors that feel intentional

(and, importantly, still look good in one color).

4) The “Fantasy Character With 47 Details”

Client sketch: A full-body character drawing with arrows: “silver armor,” “blue cloak,” “scar here,” “ring here,” “dragon tattoo,” “also a cat.”

Delivered art: A readable character design where the details support the silhouette, the cat has purpose (emotional support familiar),

and the whole design looks like it could step directly into a game cinematic.

5) The “Make It Look Like Me (But, You Know… Better)”

Client sketch: A face circle with hair scribbles. Note: “Same vibe but glowing.”

Delivered art: A flattering portrait that keeps recognizable features while polishing lighting, proportions, and color harmony.

The client still looks like themselvesjust like they slept eight hours and drank water on purpose.

So… Should Clients Always Send Sketches?

If you can sketch, yes. If you can’t sketch, also yesjust sketch anyway. A “bad” sketch is still information.

It’s the difference between:

- “I want something cool” (cool like what, specifically?)

- and “I want this kind of cool” (ah, now we’re speaking the same language).

And if you truly refuse to draw? That’s fine. Replace the sketch with a mood board, references, and a bullet list of must-haves.

The goal isn’t art. It’s clarity.

Conclusion: The Comparison Isn’t the PointThe Collaboration Is

The reason these side-by-side posts are so satisfying isn’t just that the final looks better. It’s that the final looks inevitable,

like the artist pulled a crystal-clear result out of a foggy idea. That’s collaboration at its best: client communicates a vision,

artist interprets it with skill, and both sides meet in the middlewhere the magic lives.

So the next time you see a chaotic doodle next to a stunning final piece, remember:

the doodle didn’t need to be good. It just needed to be honest.

Experience Corner: What Artists and Clients Commonly Learn the Hard Way (500+ Words)

The “client sketch vs delivered art” trend is entertaining, but it also reflects a bunch of real patterns artists talk about again and again.

Think of this section as a greatest-hits album of commission experiencesno names, no drama, just the lessons that keep popping up.

The Napkin Sketch That Saves the Whole Project

One of the most common stories artists share is how a terrible sketch actually prevents misunderstandings. A client might send a photo of a napkin

with a wobbly drawing and three arrows that say “bigger,” “closer,” and “like this.” The sketch isn’t pretty, but it reveals the intended composition:

where the subject sits, what’s foreground vs background, and what the “main moment” is. Without it, the artist might build a scene from the written description

and discoverafter hours of workthat the client imagined a totally different angle. In that sense, the napkin sketch is basically a project manager wearing a tiny cape.

The “Make It Pop” Translation Problem

Clients often use words that mean something to them but not something specific to a workflow. “Pop,” “vibrant,” “more dynamic,” “less flat,” “more premium.”

Artists learn to ask follow-up questions like, “Do you mean higher contrast? More saturated color? Stronger lighting direction? More texture?”

When the artist translates vague feedback into visual options (“Version A has bolder highlights; Version B has a tighter palette”), the project usually calms down fast.

The client feels understood, and the artist stops guessing what “premium” means in the client’s brain at 2 a.m.

When the Client Sketch Is Too Detailed

The opposite problem happens too: clients sometimes send a sketch that’s extremely specificevery accessory, every fold in the cape, every strand of hair.

That can be helpful, but it can also lock the project into a design that doesn’t work once you apply real anatomy, perspective, or composition.

Experienced artists often respond by saying, “I understand the elements you wantlet me do a few thumbnails to keep the spirit but improve readability.”

The best outcomes happen when the client is clear about priorities (“the necklace matters; the exact shoe style doesn’t”) and lets the artist solve the visual puzzle.

The Revision Spiral (and How Sketch Approval Stops It)

Many artists describe the “revision spiral” as the moment a project shifts from collaboration to endless tweaking:

a little change triggers another change, then another, and suddenly the work is being rebuilt piece by piece. This often happens when the direction

wasn’t fully approved early, or when the client changes their mind midstream without realizing they’re changing the assignment.

Clear checkpoints help: approve the composition, then approve the refined sketch, then approve the color direction. If everyone signs off,

final-stage feedback stays in the “polish” zone instead of the “redo the concept” zone. Clients don’t feel shut down; they feel guided.

Artists don’t feel trapped; they feel protected.

The Best Briefs Are Weirdly Simple

Artists often say the easiest commissions aren’t the longest briefsthey’re the clearest. The best ones tend to include:

a short description, a quick sketch, two or three references, and a list of must-haves. The client doesn’t try to micromanage the rendering process.

They communicate intent (“playful,” “nostalgic,” “dramatic”), constraints (“needs to fit a square,” “must include this text”), and context (“gift,” “brand,” “merch”).

Then they let the artist do what they hired them for: make the thing look good.

That’s why people love these comparisons. They’re funny, surebut they’re also a reminder that creative work is a partnership.

The sketch is the handshake. The final is the high-five.