Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Bessemer Was Measuring (and Why the Number Hit So Hard)

- A Quick Timeline: From Peak Cloud Euphoria to “SaaSacre”

- So… Did the Cloud Break?

- Why Cloud Market Caps Fell: The Unsexy Math Behind a Very Sexy Selloff

- “But Our Revenue Is Still Growing.” Exactly.

- Who Got Hit the Hardest in the Cloud Selloff?

- Private Markets: The Public Reset Becomes Your Next Board Meeting

- What Founders and Operators Actually Did When $1T Vanished

- 1) Re-forecast like an adult

- 2) Treat burn multiple like a real KPI

- 3) Get serious about packaging and pricing

- 4) Improve sales efficiency before “adding more reps”

- 5) Embrace FinOps and cost visibility

- 6) Make retention a company-wide sport

- 7) Communicate with investors like a partner, not a performer

- What Investors Learned (Besides “Don’t Pay 30x Forward Revenue Forever”)

- Bottom Line: The Cloud Didn’t ShrinkThe Price of Growth Reset

- Field Notes: Experiences from the $1T Cloud Market-Cap Reset (500+ Words)

- Experience 1: The CFO who had to “re-price reality” overnight

- Experience 2: Sales leaders discovering that “more activity” wasn’t the answer

- Experience 3: Product teams turning cost awareness into a feature, not an afterthought

- Experience 4: Founders shifting from “fundraising mode” to “endurance mode”

- Experience 5: Teams learning that morale is an operational system

If you were building (or buying) cloud software in early 2022, you probably felt like someone quietly moved the floor down a few inches. Not enough to

fall through, but enough to make you spill your coffee.

Bessemer Venture Partners (BVP) put a big, memorable number on what many founders, operators, and investors were already seeing in their dashboards and

cap tables: roughly $1 trillion in public SaaS and cloud market capitalization evaporated year-to-date. That headline wasn’t just

dramaticit was a fast way to describe a brutal re-pricing of growth.

This article breaks down what that “$1T” really means, how Bessemer tracks it, why the selloff happened even while cloud adoption kept climbing, and

what practical lessons teams pulled out of the chaos (without resorting to “just do more with less” motivational posters).

What Bessemer Was Measuring (and Why the Number Hit So Hard)

Market cap sounds abstract until it isn’t. In plain English: market capitalization is the value the public markets assign to a company (share price

multiplied by shares outstanding). When an entire sector loses a giant chunk of market cap, it’s a signal that investors collectively decided:

“Same companies, new price tag.”

Bessemer doesn’t measure cloud performance by vibes. It has tracked public cloud companies for years, and in 2018 it partnered with Nasdaq to create

the BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index (EMCLOUD), an index meant to represent emerging public companies delivering cloud-based software and

services (think subscription and usage-based cloud businesses rather than legacy on-prem licenses with a cloud sticker slapped on the box).

Why an index matters (even if you never trade it)

A single stock can drop for a thousand reasons. An index is different: it’s a sector-level mood ring. When the cloud index sinks sharply, it reflects

a broad reset in how markets price growth, risk, and future cash flows across the category.

In other words, Bessemer wasn’t saying, “One cloud company had a bad quarter.” It was saying, “The market changed the rules of the gamemid-season.”

A Quick Timeline: From Peak Cloud Euphoria to “SaaSacre”

The most important part of this story is that the cloud itself didn’t suddenly stop working. Customers didn’t wake up and say, “Actually, spreadsheets

are back.” What changed was the cost of capital and the valuation math that sits on top of the business.

1) The peak

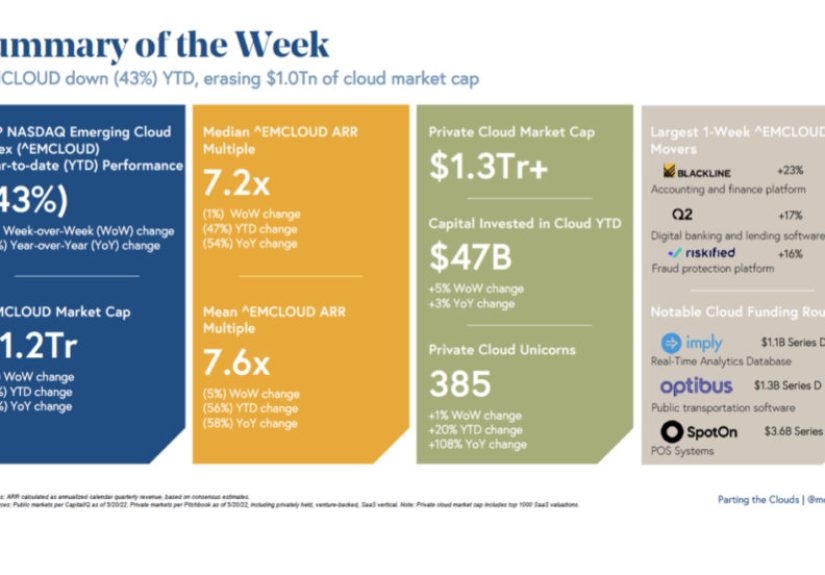

In the run-up to 2022, public cloud valuations reached a high-water mark. Bessemer noted that total public cloud market capitalization reached

about $2.7 trillion at a peak in November 2021.

2) The drop

By spring 2022, the narrative flipped. Bessemer described the EMCLOUD cohort as having dropped by 40%+, sliding back to roughly

2020 levels in index terms. Around the same period, reporting summarized a steep fall in the “public cloud index” valuefrom the high $2T range down

to the mid $1T rangerepresenting more than a trillion dollars in value shaved off in a matter of months.

3) The psychological punch

“$1 trillion” is sticky because it’s not a normal KPI. It’s a skyscraper-sized number that forces a question: if public markets can remove that much

value so quickly, what does that mean for private valuations, fundraising, and exit expectations?

One especially sobering ripple effect: as public comps fell, the pool of cloud “decacorns” (companies valued at $10B+) shrank significantly, adding

pressure to private unicorns hoping to grow into premium public multiples later.

So… Did the Cloud Break?

No. The cloud didn’t break. The pricing broke. Or more accurately: the pricing changed from “growth at almost any cost” to “growth, yesbut

show me the path to durable cash generation.”

Bessemer’s own point in its State of the Cloud analysis was that despite the selloff, the cohort still showed strong operating fundamentalshealthy

growth, high gross margins, and improving efficiency. That contrast is what made the moment so weird: the businesses didn’t implode, but the market

value did.

Why Cloud Market Caps Fell: The Unsexy Math Behind a Very Sexy Selloff

Cloud software companies are often “long-duration” assets. That means a large portion of their expected value comes from cash flows far in the future.

When interest rates rise and money becomes more expensive, those future cash flows get discounted more heavily. Translation: investors pay less today

for profits they’ll receive years from now.

Higher rates changed the valuation equation

- Discount rates rose, so future earnings were worth less in today’s dollars.

- Risk appetite fell, so investors rotated away from high-multiple growth stocks.

- Comparables reset, pulling down valuation benchmarks for the whole sector.

The result wasn’t subtle. Public cloud valuation multiples compressed sharplymoving from the “20x forward revenue is normal, right?” era into a world

where single-digit and low double-digit revenue multiples reappeared like an old coworker you forgot you still owed a favor.

Multiple compression: a simple example

Imagine a cloud company growing quickly with $200M in ARR. In a high-multiple environment, it might trade at 20x ARR (or a similar forward revenue

multiple), implying a $4B enterprise value. If the market resets that multiple to 8x, the enterprise value becomes $1.6Bwithout the company changing

its product, customers, or revenue.

That’s how you lose huge market cap “without” losing customers: it’s a repricing event, not necessarily a product failure.

“But Our Revenue Is Still Growing.” Exactly.

The cloud economy is big enough to contain two truths at the same time:

(1) public cloud valuations can fall and (2) cloud revenue can keep rising.

Even during the 2022 correction, hyperscalers and major cloud platforms continued to report meaningful cloud revenue growth in their financial filings

and annual reports. Meanwhile, the broader public cloud cohort still reflected strong fundamentals in aggregate, according to Bessemer’s own analysis.

The lesson is uncomfortable but useful: markets can punish “how you’re priced” even when customers reward “what you do.”

That’s not fair, but it’s a thing. (Capital markets are not built for fairness; they’re built for pricing risk in bulk.)

Who Got Hit the Hardest in the Cloud Selloff?

While the decline was broad, it wasn’t perfectly even. Several patterns showed up repeatedly:

1) High-growth, high-burn companies

Companies that relied on heavy spending to sustain growth faced a double whammy: multiples fell, and investors demanded clearer payback periods.

If your go-to-market model needed constant fuel and the fuel got expensive, the market noticed.

2) “Nice-to-have” categories

In tighter environments, buyers scrutinize budgets. Tools that clearly reduce costs, mitigate risk, or generate revenue tend to hold up better than

tools that are merely “cool” or “helpful on a good day.”

3) Companies with weaker net retention or choppy usage

When investors shift from growth stories to durability, metrics like net dollar retention, churn, gross margin quality, and expansion behavior become

louder than brand buzz.

4) Businesses priced for perfection

Some companies didn’t “deserve” a collapse operationallyyet they were valued as if nothing could ever go wrong. When perfection is priced in,

reality always shows up eventually. Usually with a chair and a very serious expression.

Private Markets: The Public Reset Becomes Your Next Board Meeting

Public market multiples don’t stay in public markets. They leakinto late-stage funding rounds, secondary transactions, IPO timing, and M&A appetite.

When public cloud comps re-rate downward, private investors re-price risk too.

Three big private-market consequences

- Longer fundraising cycles and more diligence around efficiency metrics.

- Down rounds or flat rounds for companies that raised at peak multiples.

- Greater emphasis on ARR quality (and the systems that make ARR durable).

Bessemer’s “Centaur” framing (the $100M ARR milestone) gained attention in this environment because it shifts the conversation from valuation headlines

to the operational engine: revenue, retention, and scalable go-to-market.

What Founders and Operators Actually Did When $1T Vanished

The best teams didn’t panicthey switched operating modes. Here are the most practical playbooks that kept showing up across the ecosystem.

1) Re-forecast like an adult

The fastest way to lose trust is to pretend nothing changed. High-performing finance teams rebuilt forecasts with scenario planning: best case,

base case, and “if the sales cycle gets 20% longer and procurement asks for a discount” case.

2) Treat burn multiple like a real KPI

Revenue growth is great. But in a re-rated market, investors want to know: how much cash are you burning to create each net new dollar of ARR?

Tightening that ratio often matters more than a flashy growth spike.

3) Get serious about packaging and pricing

Many teams leaned into clearer value-based packaging:

- Reduce confusing plan sprawl

- Align pricing to customer outcomes

- Build upgrade paths that don’t require a miracle to justify

- Make renewals boring (boring renewals are elite)

4) Improve sales efficiency before “adding more reps”

In 2021, hiring was a strategy. In 2022, hiring became a question. Teams obsessed over pipeline quality, win/loss analysis, ramp time, and

segmentation rather than brute-force headcount.

5) Embrace FinOps and cost visibility

Cloud buyers became more cost-conscious, and vendors had to respond. Products that helped customers manage spendor that clearly justified their own

costhad a stronger story in a budget-constrained world.

6) Make retention a company-wide sport

In a multiple-compression environment, retention is the closest thing to a valuation shield. Teams invested in onboarding, customer health scoring,

better in-product education, and more disciplined expansion motions.

7) Communicate with investors like a partner, not a performer

The strongest updates weren’t “Everything is amazing!” They were: “Here’s what changed, here’s what we measured, here’s what we’re doing, and here’s

how we’ll know it’s working.” Clarity beats charisma when markets are grumpy.

What Investors Learned (Besides “Don’t Pay 30x Forward Revenue Forever”)

The cloud correction didn’t cancel the cloud. If anything, it sharpened the distinction between:

companies that compound value and companies that only looked expensive because everyone else was expensive too.

Investors leaned harder into measurable quality: gross margin durability, net retention, sales efficiency, and credible paths to free cash flow.

The EMCLOUD benchmark (and products that track it) remained useful as a way to understand where the market sits on the optimism-to-skepticism spectrum.

For example, some funds explicitly track the performance of the underlying cloud index to understand category rotation and sentiment. That doesn’t mean

“trade the index,” but it does mean: know what public comps are saying before you price private risk.

Bottom Line: The Cloud Didn’t ShrinkThe Price of Growth Reset

Bessemer’s $1 trillion headline captured a defining moment: the market’s sudden decision to stop overpaying for distant future profitat least for a

while. The correction was painful, but it also forced healthier operating discipline across the ecosystem.

If you’re building in cloud today, the “lesson” isn’t to fear public markets. It’s to build a company whose value doesn’t depend on a single multiple

staying inflated forever. Grow, yes. But grow with durabilityso even if the market throws a tantrum, your business keeps compounding.

Field Notes: Experiences from the $1T Cloud Market-Cap Reset (500+ Words)

To understand the $1 trillion drop, it helps to look beyond charts and into the day-to-day experiences of teams living through a re-pricing. Not as

a dramatic “war story,” but as a set of operational moments that repeated across hundreds of cloud companies.

Experience 1: The CFO who had to “re-price reality” overnight

In boom times, a forecast can be optimistic and still be forgiven. In a correction, the forecast becomes a credibility test. One of the most common

experiences was the finance leader rebuilding the model from scratch: new assumptions for pipeline conversion, longer procurement cycles, more discount

pressure, and slower expansion. The best versions of this weren’t doom-and-gloom; they were a calm reset. “Here’s our base case, here’s our downside,

here’s what we’ll cut first, and here’s what we will never cut because it protects retention.” That clarity gave boards something to anchor to when

valuations were sliding.

Experience 2: Sales leaders discovering that “more activity” wasn’t the answer

When buyers get cautious, the temptation is to crank outbound volume. But many teams learned that activity inflation doesn’t fix trust friction.

Instead, top sales orgs got tighter: better qualification, sharper ICP definition, more proof in the first call, and more honest ROI narratives.

“We can save you money” started to outperform “We can help you grow someday.” Sales enablement shifted from hype decks to customer stories, benchmarks,

and implementation plans. The wins weren’t always biggerthey were cleaner. And clean wins compound.

Experience 3: Product teams turning cost awareness into a feature, not an afterthought

In a market reset, customers stare harder at their cloud bills. That customer behavior flowed upstream into product roadmaps. Teams that had treated

cost visibility like a “nice extra” suddenly moved it into the core experience: usage dashboards, admin controls, alerts, and clearer packaging.

Even companies not selling FinOps tools adopted a FinOps mindset: reduce waste, make consumption predictable, and ensure customers can explain the

spend internally. The product lesson was subtle but powerful: if your customer can’t defend your invoice in a budget meeting, you don’t have retention

you have temporary permission.

Experience 4: Founders shifting from “fundraising mode” to “endurance mode”

A lot of founders experienced a psychological gear change. In frothy markets, raising money can feel like a parallel track to building the product.

During the correction, fundraising became slower, more selective, and more metrics-driven. Some founders paused raises entirely and focused on runway.

Others pursued smaller rounds, secondaries, or structured deals. The most resilient founders treated the shift as a design constraint: “How do we build

a company that survives on customer revenue?” That meant prioritizing retention, tightening scope, and sometimes saying “no” to growth experiments

that looked exciting but didn’t pay back.

Experience 5: Teams learning that morale is an operational system

When valuations fall, it’s not just the cap table that changes. Hiring plans change. Promotions slow. Anxiety rises. Teams that performed best didn’t

pretend everything was finethey explained what was happening in human terms, gave measurable goals, and celebrated execution. Leaders who communicated

clearly (“Here’s our plan, here’s the runway, here’s what success looks like this quarter”) reduced rumor-driven stress. The lesson: morale doesn’t

come from pep talks. It comes from clarity, fairness, and momentum.

Put together, these experiences show what the $1T headline really represented: not just lost market cap, but a broad shift in how cloud companies were

expected to operatemore disciplined, more efficient, and more focused on durable value.