Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What does “remission” actually mean?

- Types of remission: complete, partial, and everything in between

- Remission vs. cure: why doctors are careful with words

- Understanding cancer recurrence

- Follow-up in remission: scans, tests, and survivorship care

- Minimal residual disease (MRD): the “microscopic” side of remission

- Living in remission: fear, hope, and daily life

- When cancer comes back: options and outlook

- Real-world experiences of remission and recurrence

- Conclusion: remission as a milestone, not the whole story

Few words can change a life quite like “You’re in remission.” If you or someone you love has heard that phrase, you probably felt a mix of relief, confusion, and maybe a little “Okay… but now what?” Remission is a huge milestone on the cancer journey, but it doesn’t always mean the story is over. It’s more like finishing one season of a very intense show and realizing there are more seasons already filmed.

In this guide, we’ll break down what “cancer remission” really means, the difference between partial and complete remission, how cancer recurrence happens, and what follow-up care and daily life can look like after treatment. We’ll also talk about new tools like minimal residual disease (MRD) testing, and share some real-world experiences of living in remissionbecause it’s not just about scans and lab results; it’s about your life.

What does “remission” actually mean?

Doctors use the word remission to describe a period when signs and symptoms of cancer have decreased or disappeared. The National Cancer Institute defines remission as a decrease in or disappearance of signs and symptoms of cancer, with partial remission meaning some signs are gone and complete remission meaning all detectable signs have disappeared on available tests.

That definition is important for two reasons:

- Remission is a medical description, not a guarantee. It tells us what doctors can see and measure right now, using today’s tests.

- Cancer can still be present at levels too small to detect. That’s why your care team may keep a close eye on you even when everything looks “clear.”

You may also hear terms like “no evidence of disease” (NED), “cancer-free,” or “in remission.” In everyday conversation, people often use them interchangeably. Medically, NED usually means there’s no detectable cancer on imaging or lab tests at this time, which typically corresponds to complete remission.

Types of remission: complete, partial, and everything in between

Complete remission

In complete remission, all signs of cancer disappear on scans, blood work, and physical exams. The NCI notes that complete remission means there is no detectable sign of cancer in response to treatment, though cancer cells may still exist at levels below current detection methods.

Think of it like turning off every visible light in a city at night. From a satellite image, the city looks dark. But a few phone screens or flashlights might still be onyou just can’t see them from that distance. Similarly, small numbers of cancer cells can remain hidden even when tests look perfect.

Partial remission

In partial remission, the cancer is still present, but it has shrunk or decreased in activity. Some guidelines describe partial remission as at least a 30–50% reduction in measurable tumor size, depending on the cancer and how it’s measured.

Partial remission is still a big win: treatment is working, and symptoms often improve. In some cancers, partial remission can be managed like a chronic condition, with ongoing treatment designed to keep the disease under control for years.

Stable disease and controlled cancer

Sometimes, your doctor may say your cancer is “stable”. That means it isn’t shrinking enough to qualify as partial remission but also isn’t growing or spreading. In other words, it’s not winning.

Many people live for long periods with stable or partially controlled cancer, especially as newer therapieslike targeted treatments and immunotherapiesturn some cancers into conditions that can be managed over the long term rather than immediately cured.

Remission vs. cure: why doctors are careful with words

The word “cured” is powerful, but in cancer care, it’s used cautiously. A cure means the cancer will not come back at all. Unfortunately, medicine can rarely promise that with absolute certainty.

Instead, doctors talk about being in remission and about lowering the risk of recurrence over time. For many solid tumors, the risk of recurrence is highest within the first few years after treatment. Several sources note that if a cancer hasn’t returned within about five years, the chance of recurrence often drops significantly, though this varies by cancer type.

So you might hear something like:

- “You’re in complete remission.”

- “Your scans show no evidence of disease.”

- “Your risk of recurrence gets lower the farther out you go.”

None of these phrases are meant to take away your joy. They’re meant to be honest about what the tests can (and cannot) prove, while still recognizing how far you’ve come.

Understanding cancer recurrence

Recurrence means cancer has come back after a period when it couldn’t be detected. This can happen weeks, months, oreven more rarelyyears after remission. Doctors usually talk about three main patterns:

- Local recurrence: Cancer returns in the same place as the original tumor.

- Regional recurrence: Cancer appears in nearby lymph nodes or tissues.

- Distant recurrence (metastasis): Cancer spreads to organs far from the original site, such as the lungs, liver, bone, or brain.

The timing and pattern of recurrence depend on the type and stage of the original cancer, its biology (for example, hormone receptor status in breast cancer), and the treatments used. Some cancers have a higher chance of coming back early, while others may recur later.

Risk factors for recurrence

While every person’s situation is unique, common factors that influence recurrence risk include:

- Stage at diagnosis: Cancers found at an earlier stage generally carry lower risk.

- Lymph node involvement: Spread to lymph nodes can increase the risk of recurrence.

- Cancer subtype and biology: Features like grade, hormone receptor status, HER2 status, or specific gene mutations matter.

- Treatment received: Surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy all affect risk differently.

- Response to treatment: Deeper responses, such as complete remission or MRD negativity, are often linked with better long-term outcomes.

Your oncology team uses these details to estimate risk and design a follow-up plan that makes sense for you.

Follow-up in remission: scans, tests, and survivorship care

The end of active treatment doesn’t mean the end of medical care. Instead, you transition into survivorship care, which focuses on:

- Monitoring for recurrence

- Watching for late or long-term side effects of treatment

- Supporting physical, emotional, and social well-being

Organizations such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommend survivorship care plans that summarize your diagnosis, treatments, potential long-term effects, and recommended follow-up schedule. These plans can be shared with primary care doctors so everyone is on the same page.

Depending on your cancer type, your follow-up may include:

- Regular physical exams and symptom checks

- Periodic imaging (such as CT, MRI, mammograms, or ultrasounds)

- Blood tests, including tumor markers or hormone levels for some cancers

- Screening for other cancers (for example, colonoscopies, skin checks)

The frequency of visits typically decreases over time if you remain in remission, but you should always call your team sooner if something feels off.

Minimal residual disease (MRD): the “microscopic” side of remission

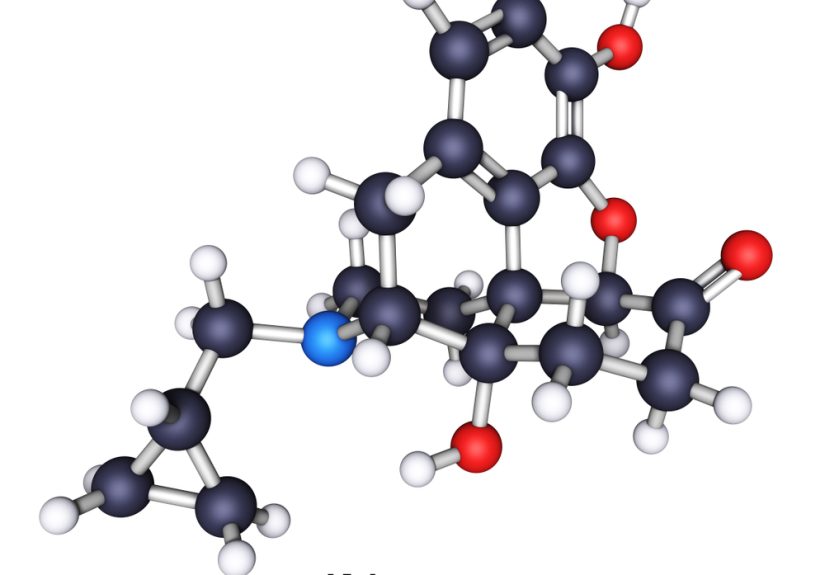

One reason remission can feel so uncertain is that standard tests can’t pick up tiny amounts of cancer. That’s where the concept of minimal residual disease (MRD) comes in.

MRD refers to cancer cells that remain after treatment but are too few to be seen on scans or standard tests. Specialized techniqueslike highly sensitive flow cytometry or genetic testing of blood or bone marrowcan sometimes detect these cells and help predict the risk of relapse.

MRD testing is widely used in certain blood cancers and is increasingly being studied for solid tumors such as colorectal, breast, and lung cancers. In some research, MRD-positive patients are more likely to experience recurrence, while MRD-negative status is associated with better outcomes.

The exciting part: MRD testing may allow doctors to:

- Identify relapse earlier than imaging alone

- Adjust treatment intensity (stepping up or scaling back therapy)

- Tailor follow-up so those at higher risk get closer monitoring

MRD testing isn’t appropriate or available for everyone, so it’s something to discuss with your oncologist, especially if you’re in remission from a blood cancer or involved in clinical trials.

Living in remission: fear, hope, and daily life

Being in remission can feel a bit like getting off a roller coaster and realizing the ground still moves. Appointments slow down, family and friends may assume you’re “back to normal,” but you might be dealing with lingering side effects, anxiety about recurrence, or big questions about the future.

A few practical ways to navigate this stage:

- Keep your follow-up appointments. They’re not just for finding recurrence; they’re also for managing symptoms, side effects, and general health.

- Know your “red flag” symptoms. Ask your doctor which signs should lead you to call the office sooner rather than later.

- Adopt healthy habits where you can. Regular movement, a balanced diet, not smoking, limited alcohol, and good sleep all support overall health and may reduce recurrence risk in some cancers.

- Use support systems. Counseling, support groups, faith communities, friends, and family can all help you navigate the emotional fallout of cancer.

- Give yourself permission to feel… everything. Relief, joy, guilt, fear, angerit’s normal to feel like they’re all sharing the same brain space.

When cancer comes back: options and outlook

Hearing “the cancer has returned” is gut-wrenching, especially after celebrating remission. But a recurrence does not mean there are no options. Many people go on to have successful treatment for recurrent disease, including new remissions.

Treatment for recurrence depends on:

- Where the cancer has come back

- How long it has been since the first treatment

- What treatments you have already received

- Your overall health, preferences, and goals

Options may include surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, clinical trials, or combinations of these. Palliative and supportive care can be involved at any stage to manage symptoms, improve quality of life, and help with decision-makingnot just at the end of life.

The bottom line: remission is a milestone, not a finish line, and recurrenceif it happensis another chapter, not the whole book.

Real-world experiences of remission and recurrence

Medical definitions are helpful, but they don’t capture what remission feels like. While everyone’s story is different, many people share common themes. The following composite experiences reflect what survivors often describe in clinics, support groups, and surveys.

“The quiet after the storm”

Imagine spending months with your calendar packed: chemo infusions, radiation sessions, lab draws, scans, and appointments with more specialists than you knew existed. Then, almost suddenly, your doctor says, “Your scans look great. You’re in remission.” The visits space out. Friends stop checking in as often. You’re grateful, but you’re also left with a strange silence.

Many people say this “quiet after the storm” is when emotions hit hardest. During treatment, the focus is survival. Afterward, questions creep in: “What if it comes back?” “Who am I now?” “Why am I still exhausted when I’m supposed to be ‘better’?” This is often when counseling or a survivorship support group makes a huge differencegiving you a place to say the things you don’t want to burden family with.

Living scan to scan

Another common experience is “scanxiety”that uneasy countdown to each follow-up scan or blood test. Even people who feel physically well can find themselves replaying worst-case scenarios in their minds in the days or weeks before results. You might notice you’re extra jumpy about minor aches, or you refresh your patient portal a little too often.

Over time, many survivors develop rituals to cope: scheduling something enjoyable after a scan, bringing a friend to appointments, practicing breathing exercises in the waiting room, or avoiding the temptation to search every symptom online at 2 a.m. Some people find it helpful to tell themselves, “Today, I know I am in remission. I will deal with new information when I have it, not before.” Easier said than donebut with practice, the emotional spikes around scans often soften.

Redefining “normal”

Remission doesn’t always mean going back to your pre-cancer life. Some people return to work and routines almost exactly as before, while others discover that their priorities, energy levels, or bodies have changed. Maybe you tire more easily, or certain foods don’t agree with you anymore. Maybe your job doesn’t feel as important, or relationships that were shaky before now feel fragileor stronger.

Many survivors talk about creating a “new normal.” That might include building exercise into your week, cooking differently, or saying “no” more often to things that drain you. Some people become advocates, volunteers, or mentors to others with cancer; others prefer to keep their experience more private. There’s no right way to live in remission, only the way that helps you feel more like yourself.

Facing a recurrence

For some, recurrence happens despite everything done “right.” That news can feel even harder the second time around, because you remember exactly what treatment was like. Yet many people report that, while recurrence is devastating, they also feel more prepared. They know the system, the questions to ask, and the side effects to watch for. They’ve already built a support network.

People often describe a shift in perspective: “The first time, I just wanted to get through treatment. The second time, I focused on how I wanted to live during treatment.” That might mean planning small trips between cycles, setting boundaries at work, or choosing treatments that balance longevity with quality of life. Recurrence doesn’t erase the strength you built the first timeit often reveals just how much of it you still have.

Permission to celebrate

One more thing survivors frequently mention: they sometimes feel guilty celebrating remission, especially if friends from treatment didn’t get the same news. It’s okay to acknowledge that mixture of joy and grief. Lighting a candle, donating to a cancer organization, sending a message to someone still in treatmentthese can be ways to honor others while also allowing yourself to feel happy about your own good news.

Remission sits in the tension between “I’m okay today” and “I don’t know about tomorrow.” That uncertainty is real, but so is your resilience. With good follow-up care, honest conversations with your team, and support for your emotional health, remission can be more than a medical statusit can be a season of rebuilding, reimagining, and, yes, celebrating.

Conclusion: remission as a milestone, not the whole story

“In remission” is one of the most hopeful phrases in cancer care, but it’s also just one chapter in a longer story. Medically, it means your cancer has shrunk or disappeared to the point that tests can’t find it. Practically, it means shifting from intense treatment to long-term monitoring, navigating the fear of recurrence, and learning to live well with uncertainty.

Understanding remission, recurrence, and tools like survivorship care plans and MRD testing can help you feel more informed and less at the mercy of every scan result. You can’t control everything, but you can control how you prepare, the questions you ask, and the support you allow yourself to receive. Remission is not just the absence of visible cancer; it’s the presence of possibility.