Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is Sonoluminescence, Exactly?

- Why the “Star in a Jar” Metaphor Isn’t Just Hype

- How Can Sound Turn Into Light?

- How Hot Is a Sonoluminescing Bubble?

- A Quick History: From Darkroom Surprise to Physics Celebrity

- What Sonoluminescence Teaches Us (Beyond Party-Trick Awe)

- The “Bubble Fusion” Question (And Why the Science Community Had Feelings)

- So… Can You Really “Capture” It?

- FAQ: The Questions Everyone Asks Once They Hear “Light from Sound”

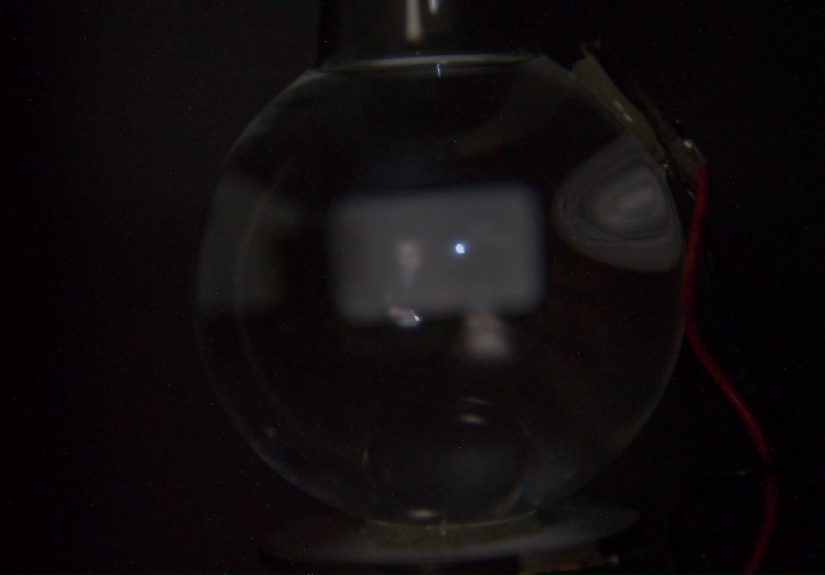

- Experiences: What It Feels Like to Watch a “Star in a Jar” (500+ Words)

- Conclusion

If you’ve ever wished you could hold a tiny star in your handswithout, you know, turning your living room into a

craterphysics has a delightfully dramatic compromise: sonoluminescence.

It’s the real phenomenon where sound squeezes a microscopic bubble so violently that it flashes with light,

like a little “blink” from the universe. The flash is so brief it makes a camera shutter look like it’s napping, and

the energy-focusing is so intense it has inspired one of the best nicknames in science: “a star in a jar.”

Before we go any further: sonoluminescence is typically produced in controlled lab setups involving high-intensity

ultrasound, specialized glassware, and careful safety practices. This article explains the science and the storynot

a DIY build. Think “planetarium tour,” not “garage rocket launch.”

What Is Sonoluminescence, Exactly?

Sonoluminescence is light emitted from a collapsing bubble in a liquid driven by sound. The bubble

expands and contracts with the pressure changes of an acoustic field. Under the right conditions, the collapse becomes

so extreme that the bubble emits a tiny pulse of light.

Two Flavors: One Bubble vs. Many

-

Multi-bubble sonoluminescence (MBSL): A whole crowd of bubbles forms and collapses, creating a glow

in the liquid. It’s flashy, but messylike trying to understand one singer by analyzing a stadium chant. -

Single-bubble sonoluminescence (SBSL): One bubble is trapped in a stable spot (often near a pressure

antinode in a standing wave) and collapses repeatedly, producing light pulses with clock-like regularity. This is

the “star in a jar” version scientists love, because it’s reproducible and easier to study.

Why the “Star in a Jar” Metaphor Isn’t Just Hype

Stars shine because gravity crushes hot gas until it radiates. A sonoluminescing bubble isn’t powered by gravity,

but it does something philosophically similar: it concentrates energynot over millions of years,

but in microsecondsinto a region smaller than a grain of dust.

During collapse, the bubble’s contents are compressed dramatically. The result is a tiny region with conditions

so extreme that the gas can partially ionize, molecules can break apart, and light can be emitted. It’s not a star

(no sustained nuclear burning, no self-gravity), but it feels star-like because it’s a miniature, transient

pocket of high-energy physics happening in a glass of liquid.

How Can Sound Turn Into Light?

The short version: acoustic cavitation. Sound waves create alternating high- and low-pressure phases.

In a low-pressure phase, a tiny bubble can expand. In the following high-pressure phase, it collapses. If the

oscillation is strong and stable enough, collapse becomes violentlike a tiny imploding trampoline.

The Collapse: A Micro-Event with Macro Drama

A single collapse can happen in less than a microsecond, with the bubble shrinking incredibly fast. In SBSL,

the flash of light is typically on the order of tens to hundreds of picosecondsa timescale so small

that “blink and you miss it” is still wildly optimistic.

What’s Emitting the Light?

Scientists have tested multiple models for decades. The leading ideas (often overlapping rather than mutually exclusive)

revolve around the bubble interior becoming extremely hot and dense at collapse:

-

Thermal emission / plasma-like behavior: The gas heats rapidly; partial ionization can occur; light

is emitted as a hot, dense mixture relaxes. -

Bremsstrahlung (“braking radiation”): If free electrons are present, their interactions with atoms

and ions can produce broad-spectrum light. -

Molecular emission and chemistry: In some conditions, emission features and reactive species show

up, connecting sonoluminescence to sonochemistry (chemistry driven by cavitation). -

Exotic proposals: Ideas like “vacuum radiation” have been explored, partly because the phenomenon is

so extreme it invites bold hypotheses. Even when a proposal doesn’t become the final answer, it often sharpens the

experiments and the measurements.

One particularly important twist: the dissolved gas matters. Trace noble gases (like argon) can

strongly affect brightness and stability. This is one reason sonoluminescence feels “finicky” in practice and why

careful control of liquid composition and gas content shows up again and again in the scientific literature.

How Hot Is a Sonoluminescing Bubble?

Temperature is one of the most famous talking points, because it’s where the “tiny star” comparison gets spicy.

Spectral measurements and modeling commonly point to effective temperatures on the order of

10,000–20,000 K in single-bubble conditions, with multibubble conditions generally lower.

That’s comparable to the surface temperature of some starsagain, for an instant, in a microscopic volume.

Importantly, those numbers come with nuance. Sonoluminescence is not necessarily in perfect thermal equilibrium,

and “temperature” can mean different things depending on how it’s inferred (continuum shape, molecular signatures,

model assumptions, and more). The big takeaway is not a single magic number, but the theme:

extreme energy focusing in a tiny, collapsing bubble.

A Quick History: From Darkroom Surprise to Physics Celebrity

1930s: The Accidental Discovery

Sonoluminescence was first observed in the 1930s during experiments with ultrasound in liquids. Early observations

involved many bubblesinteresting, but chaotic and hard to analyze in detail.

1960: A Thermal Explanation Enters the Chat

By 1960, researchers like Peter Jarman were already arguing that the phenomenon likely had a fundamentally

thermal origin connected to rapid bubble collapse and microshocks.

1990s: The Single-Bubble Breakthrough

The field took off when stable single-bubble sonoluminescence was demonstrated and studied in depth.

With one bubble producing repeated, synchronized flashes, the phenomenon became a precision target: measure the light,

time the pulse, analyze the spectrum, and try to match it to bubble dynamics.

Researchers such as Seth Putterman and collaborators helped popularize and analyze SBSL, pushing it into the spotlight

as a “how is this even possible?” problem that sits at the intersection of fluid dynamics, acoustics, and plasma physics.

What Sonoluminescence Teaches Us (Beyond Party-Trick Awe)

Sonoluminescence is not just a cool flash; it’s a laboratory window into extreme conditions created by everyday physics.

Here are the areas it informs:

1) Cavitation and Fluid Dynamics

Cavitation is a major player in engineeringsometimes helpful (ultrasonic cleaning), sometimes harmful (propeller erosion).

Sonoluminescence is a vivid signal that a bubble collapse has entered the “seriously intense” regime, making it useful

for understanding bubble stability, shock formation, and nonlinear motion.

2) Sonochemistry: Chemistry Powered by Bubble Collapse

Collapsing bubbles can generate reactive species (like radicals) and drive chemical transformations. Sonochemistry is

used in research on synthesis, degradation of pollutants, and reaction pathways that are hard to access with gentler energy inputs.

Sonoluminescence is often treated as a cousinor a diagnosticof these high-energy chemical microenvironments.

3) Measurement and Modeling Under Extreme Conditions

The bubble flash is a test for scientific humility. Tiny changes in dissolved gas, temperature, or acoustic conditions

can noticeably change outcomes. That makes sonoluminescence a training ground for careful experimental design:

control variables, calibrate detectors, replicate results, and keep your excitement on a leash until the error bars agree.

The “Bubble Fusion” Question (And Why the Science Community Had Feelings)

In the early 2000s, sonoluminescence gained pop-culture attention when some researchers suggested that collapsing bubbles

in certain conditions might produce nuclear fusion (“sonofusion” or “bubble fusion”).

The claim was controversial from the start, and later investigations centered on research conduct and how “independent confirmation”

was represented. Today, the safest, evidence-based summary is:

sonoluminescence is real and repeatable; bubble fusion remains unestablished and disputed.

If sonoluminescence is the tiny “star,” the fusion story is the cautionary tale about how extraordinary claims demand

extraordinarily careful verification.

So… Can You Really “Capture” It?

You can’t bottle the flash like a lightning bug and carry it around in your pocket. The light isn’t storedit’s produced

by a precise, repeating collapse driven by an acoustic field. The “jar” is basically a controlled environment where

pressure waves do their work and the bubble stays stable long enough to act like a microscopic strobe light.

If you’re curious to see it, the best route is safe, supervised demonstrationuniversity outreach,

museum events, or recorded lab demonstrations from reputable institutions. Sonoluminescence setups can involve intense

ultrasound, fragile glassware, and specialized equipment, which is why it belongs in the “trained hands and safety protocols”

category, not the “weekend craft” category.

FAQ: The Questions Everyone Asks Once They Hear “Light from Sound”

Is it actually a star?

Not literally. A star is a self-gravitating plasma that shines continuously because of internal energy sources.

Sonoluminescence is a tiny, transient burst of light created by forced bubble collapse. The analogy is about

energy concentration and temperature scale, not about being an actual astrophysical object.

Why is the light often blue-ish?

Many observations show a strong continuum extending into the ultraviolet. When you see it with the naked eye (or cameras),

the visible portion often skews blue. The exact spectrum depends on conditions, gas content, and how the light is measured.

Does it produce meaningful heat outside the bubble?

The energy is highly concentrated but extremely localized and brief. The surrounding liquid is a giant heat sink compared

with the bubble. So while the bubble interior can be “hot” in a physical sense, the overall system doesn’t become a mini furnace.

Why does the type of gas matter so much?

Different gases compress, ionize, and emit light differently. Noble gases can alter stability and emission intensity.

Even small changes in dissolved gas concentration can shift what the bubble does during collapse.

Experiences: What It Feels Like to Watch a “Star in a Jar” (500+ Words)

Imagine you’re in a dim lab where the lights are turned downnot for drama, but because the event you’re watching is

genuinely tiny. A flask sits in a holder like it’s about to be interviewed for a documentary. It looks ordinary:

clear liquid, glass walls, no smoke, no sparks. If you walked past it in a kitchen, you’d assume it was waiting for

lemonade. But this is a setup designed to make pressure waves behave like precision tools.

At first, nothing happens. That’s part of the experience: the anticlimax before the “oh!” moment. The equipment hums

in that way machines do when they’re working hard but staying polite. Someone adjusts controls with the careful calm

of a person who has learned that “close enough” is not a scientific measurement. You stare at the liquid like you’re

trying to catch a whisper with your eyes.

Thenthere it is. A tiny, steady flash, right where the bubble is trapped. Not a big flare. Not fireworks. More like

a microscopic camera flash that decided to get a PhD. It appears as a pinpoint of light that’s almost too small for

your brain to trust. The immediate human reaction is to doubt yourself:

Did I really see that? And then it keeps happeningagain and againso regular that your skepticism starts

losing the argument.

What makes it feel “star-like” isn’t the brightness (it’s not lighting up the room), but the weird emotional mismatch:

you’re watching something that looks delicate, yet you’re told it comes from a collapse violent enough to create

extreme conditions inside a microscopic bubble. Your intuition wants small things to do small things. Sonoluminescence

is a reminder that nature doesn’t negotiate with intuition.

If you lean into the experience, the lab becomes a stage for scale. On one side: a container you can hold with one hand.

On the other: temperatures and pressures that sound like astronomy. You start thinking in layers: the glass, the liquid,

the bubble, the collapse, the flash. And suddenly “a bubble in water” doesn’t feel like a simple ideait feels like a

whole universe of physics hiding in plain sight.

There’s also something oddly comforting about the regularity. A flash every cycle, synchronized to a wave you can’t see.

It’s a physical metronome, ticking in light instead of sound. People who love science demonstrations often describe that

moment when curiosity turns into wondernot because the thing is loud or huge, but because it’s precise. Sonoluminescence

sits in that sweet spot: mesmerizing because it’s repeatable, and repeatable because someone cared enough to understand

the details.

And when you step back into normal lighting, the memory of that tiny flash follows you. Not because you witnessed a new

star being born, but because you saw how far ordinary forces can go when they’re focused. The “star in a jar” isn’t a

souvenir. It’s a new mental imageone you can carry into every other “simple” phenomenon and quietly wonder,

What else is hiding in there?

Conclusion

Sonoluminescence earns its reputation because it’s both simple and outrageous: a bubble, a sound field, and a flash of light

that hints at extreme conditions. It’s a reminder that nature can concentrate energy with breathtaking efficiencyand that

some of the most interesting physics doesn’t require a telescope, only the right way to listen to a liquid.