Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The headline story: “Child Services is investigating our fetus”

- Can child services investigate before a baby is born?

- Why do referrals happen even when parents think they’ve done nothing wrong?

- When the knock is real: what a typical child welfare contact looks like

- When the knock is NOT real: impersonators, intimidation, and scams

- What to do if “child services” shows up at your door

- Step 1: Stay calm and treat it like an identity-verification problem

- Step 2: Ask for ID and write down details

- Step 3: Verify using an official phone number you find yourself

- Step 4: Don’t share sensitive info on the spot

- Step 5: If it’s real, you can still set boundaries

- Step 6: If it seems fake, contact local authorities

- If the report is legitimate: how to protect your family without panic-spiraling

- FAQ: quick answers parents search at 2 a.m.

- The takeaway

- Experiences families share about pregnancy-era child welfare scares (added perspective)

- 1) “We thought we were being investigated, but it was really discharge planning.”

- 2) “A rumor turned into a report, and we got pulled into proving a negative.”

- 3) “We met a great caseworker… and then the system changed midstream.”

- 4) “The scariest moment was the not-knowing: is this real, and who do we call?”

- 5) “We learned to advocate without turning the interaction into a fight.”

Picture this: you’re halfway through pregnancy, your feet are swollen, you’re debating whether cereal counts as dinner (it does), and your doorbell rings. On the porch stands a stranger with a serious face who says something like, “I’m with Child Services. We’re here about your fetus.”

That sentence is so bizarre it doesn’t even sound real. Yet stories like this go viral because they hit two primal fears at once: someone messing with your family and the system being bigger than you. In one widely shared account, a couple was left rattledthen stunnedafter discovering the “investigation” wasn’t what it seemed.

This article breaks down what can actually happen in the U.S. when child welfare gets involved around pregnancy, why referrals happen (even when parents aren’t doing anything wrong), what “Plans of Safe Care” are, and how to protect yourself if the knock at your door is… not official.

The headline story: “Child Services is investigating our fetus”

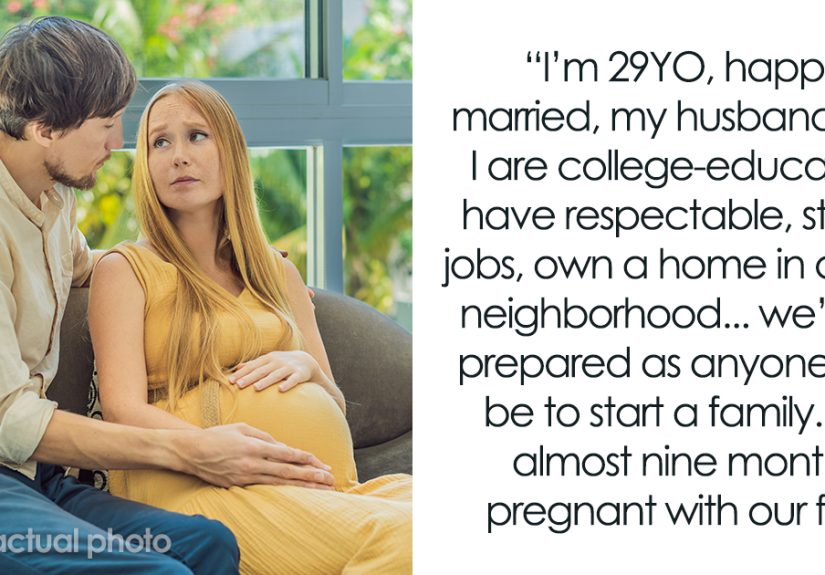

In the viral version of events, an expectant couple described a tense visit from a woman claiming to be with a state child services agency (often called CPS, DCS, or DCFS depending on where you live). The visitor allegedly said the agency had received a report that the parents were using drugs and that the unborn baby was “at risk.” She referenced personal details about the family and pushed for immediate “proof” and cooperation.

The couple did what many people would do in panic mode: they tried to figure out whether this was real, what rights they had, and how a child welfare agency could be investigating an unborn baby in the first place.

Then came the twist. After checking directly with the actual agency and comparing details, the couple concluded the visitor wasn’t a real caseworker at alljust someone impersonating one. That “truth” flips the story from “shocking government overreach” to something equally unsettling: someone may be using the fear of child welfare to intimidate, harass, or scam families.

So, let’s get grounded in reality: can child services get involved during pregnancy? Sometimes. But the “how” matters a lotand it’s not the same everywhere in the U.S.

Can child services investigate before a baby is born?

Short version: in many places, child welfare involvement is centered on the child after birthespecially around hospital delivery and newborn safety checks. But some states allow certain kinds of pre-birth interventions or court involvement in narrow circumstances.

Federal baseline: CAPTA is mostly about infants (not fetuses)

At the federal level, the big law people reference is the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA). CAPTA ties federal funding to state child protection requirements, including how states respond to infants affected by prenatal substance exposure.

Under CAPTA (as amended over time), states receiving certain grants must have policies for when health care providers notify child protective services that an infant is born and identified as affected by substance abuse/withdrawal symptoms from prenatal drug exposure, or has fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. States also must address the development of a Plan of Safe Care to support the infant and the family/caregiver.

Notice the key word: infant. CAPTA’s core requirements generally attach when a baby is born and identified as affectednot simply because someone is pregnant.

State variation: some states go further

Where things get complicated is state law. States decide what “notification” means in practice and whether prenatal concerns can trigger action. Some states treat prenatal substance use as child neglect/abuse under civil child welfare law; others explicitly say prenatal exposure alone isn’t automatically abuse; many fall somewhere in between.

There are also a few well-known examples of states with policies that can reach into pregnancy more directly. For instance, Wisconsin has a law (often discussed as a fetal protection or “unborn child” law) that can allow court involvement and even custody-related actions involving an “expectant mother” under certain defined criteria. Other states have their own approaches, but the big takeaway is this:

- Your zip code matters. “Can CPS investigate a fetus?” is not a one-size-fits-all question.

- Most child welfare activity still clusters around birth (hospitals, newborn screening, discharge planning), not random doorstep interrogations about a pregnancy.

Why do referrals happen even when parents think they’ve done nothing wrong?

People imagine CPS calls come from dramatic situations. Sometimes they do. But plenty of referrals are more mundaneand that’s where misunderstandings bloom.

1) Mandatory reporting and “better safe than sorry” paperwork

Doctors, nurses, social workers, teachers, and other professionals are often mandatory reporters for suspected abuse or neglect. Around childbirth, hospitals may have protocols that trigger a social work consult or a notification to child welfare based on risk factors, past history, or specific test results.

Even when a family is stable, referrals can happen due to:

- Confusion about what a medical result means (or whether it’s confirmed).

- Old records (a past substance charge, a prior family court issue, a previous CPS contact) that still appear in databases.

- Miscommunication between departments (OB, ER, pediatrics, social work).

- A report made in good faith that turns out to be wrong.

2) “Notification” doesn’t always mean “abuse report,” but it can feel like it

CAPTA uses the idea of notification and Plans of Safe Care to connect families to services and ensure newborn safety. In practice, states interpret and implement this differently. In some places, a notification may not be treated the same as an allegation of abuse. In others, it can open an assessment pathway that feels very similar to an investigation.

That gap between policy language and lived experience is where parents often feel blindsided. You might hear “We need to do a plan,” and what you feel is, “Someone thinks we’re unfit.”

3) Bias and uneven enforcement can raise the temperature

Multiple researchers and public health groups have documented that reporting and testing practices can be inconsistent, and that families can experience the system very differently based on race, income, and hospital policies. That doesn’t mean every referral is unfairbut it does mean families’ fears are not coming out of nowhere.

When the knock is real: what a typical child welfare contact looks like

If CPS/DCS/DCFS is legitimately involved, the contact is usually more structured than a mysterious doorstep demand about your pregnancy. Common, more realistic patterns include:

Hospital-based contact around delivery

A hospital social worker may speak with parents if there’s a concern noted in the chart, a positive toxicology screen, or a need to coordinate services. A Plan of Safe Care may be discussed, especially if a newborn is identified as substance-affected under state definitions.

Follow-up after birth

A caseworker might contact you after discharge to confirm safe sleeping arrangements, pediatric follow-up, or connections to services (home visiting programs, treatment referrals, parenting supports).

Occasional pre-birth planning (less common, but possible)

Some jurisdictions coordinate pre-birth plans in higher-risk situations (for example, a parent already has an open case involving other children, or there is a court-involved scenario under state law). This is usually not a surprise “show me your belly” momentit’s a documented process with names, supervisors, and paperwork.

When the knock is NOT real: impersonators, intimidation, and scams

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: government impersonation scams exist, and the “child services” angle can be especially effective because it triggers fear and urgency.

In different parts of the U.S., there have been warnings and news reports about people impersonating social workers or child services staff. Sometimes the goal is information (names, dates of birth, insurance details). Sometimes it’s access to the home. Sometimes it’s straight-up harassment disguised as “official business.”

And unlike a fake bank text, a fake caseworker can feel terrifyingly believablebecause real caseworkers do show up unannounced at times, and real investigations can be stressful.

Red flags that should make you slow down

- No clear identification (badge, photo ID, agency information you can independently verify).

- Refusal to give a case number or supervisor contact.

- Pressure to act immediately (“Do this right now or else”) without explaining the formal process.

- Demands that don’t match normal procedure (especially invasive or weird requests that sound like something from a prank video, not a public agency).

- They don’t want you to call the agency directlyor they insist you only call a number they provide.

Also: if someone shows up and their story seems stitched together from gossip, social media, or a background check, that’s a clue. Some impersonators rely on partial truths to sound official.

What to do if “child services” shows up at your door

This is not legal advice, but these steps are widely recommended for safety and verification.

Step 1: Stay calm and treat it like an identity-verification problem

You’re not deciding your entire family’s fate on the porch. You’re verifying whether the person is who they say they are.

Step 2: Ask for ID and write down details

- Full name

- Agency name

- Badge/ID number

- Supervisor name

- Case number (if there is one)

Step 3: Verify using an official phone number you find yourself

Look up the agency’s main line or hotline from a trusted source (official state/county website). Call and ask whether that person is an employee and whether there is an active matter associated with your name/address.

Step 4: Don’t share sensitive info on the spot

Don’t hand over documents, Social Security numbers, medical records, or anything that could be used for identity theft. And don’t agree to “tests” or services based on a stranger’s demand at your door.

Step 5: If it’s real, you can still set boundaries

Real child welfare agencies may request to speak with you and may ask to enter your home, but entry rules vary by state and situation. Many agencies explain the allegation, request consent to enter, and document what happens if consent is refused. If you’re unsure, you can ask to schedule a time, request a supervisor, or speak to an attorneyespecially if the situation feels complex.

Step 6: If it seems fake, contact local authorities

Impersonating a government worker can be a crime. If you believe someone is impersonating a caseworker, report it to the agency and local law enforcement. If you can do so safely, keep any written materials, cards, or vehicle details.

If the report is legitimate: how to protect your family without panic-spiraling

If child welfare contact is real, the goal is usually to assess safety and connect supportsnot to “gotcha” parents for sport. Even so, the experience can feel invasive. Here are practical ways to navigate it:

Document, document, document

- Keep a simple log of calls, visits, names, and dates.

- Ask for written information about the concern and next steps.

- Save copies of paperwork you receive or sign.

Keep your prenatal care and follow-ups organized

Regular prenatal care, pediatric appointments after birth, and a clear plan for baby basics (safe sleep setup, car seat, feeding plan, support person) can reduce confusion and show readiness.

Understand what a “Plan of Safe Care” is meant to be

A Plan of Safe Care is typically described as a coordinated plan to support the infant’s safety and well-being and address caregiver needs. In the best-case implementation, it’s about connecting families to services (health care, treatment if needed, home visiting, mental health support, parenting resources)not automatic punishment.

Ask questions like a project manager

Yes, this is emotionally loaded. But practical questions help:

- What exactly is the concern being assessed?

- What needs to happen for this to close out?

- What services are optional vs. required?

- Who is the supervisor if I have concerns?

FAQ: quick answers parents search at 2 a.m.

Can CPS take your baby because you used substances earlier in pregnancy?

It depends on state law, what “use” means (prescribed vs. non-prescribed, confirmed vs. suspected), whether the newborn is identified as affected, and whether there are other safety concerns. Many cases result in service referrals or safety planning rather than removal, but policies vary widely.

Can CPS investigate a fetus?

In most places, child welfare involvement is tied more directly to the baby after birth. Some states have pathways for pre-birth court involvement under specific statutes or when there is already an open child welfare case involving other children.

Do you have to let a caseworker into your home?

Often, agencies request consent to enter. Rules about entry, warrants, and emergencies vary by jurisdiction. If you’re unsure, you can ask for clarification, request a supervisor, or seek legal counsel.

How do you tell a real caseworker from a fake one?

Real workers can be verified through official agency channels, have proper identification, and can provide documentation and supervisor contacts. If someone pushes you not to verify them independently, that’s a flashing neon warning sign.

The takeaway

A “child services investigation of a fetus” sounds like a dystopian headline, but the truth is more nuanced. U.S. policy is a patchwork: federal rules focus on infants affected by prenatal substance exposure and Plans of Safe Care, while state laws and local implementation shape what families actually experience.

And when a viral story ends with “the visitor wasn’t even real,” it highlights a different kind of vulnerability: people can weaponize the fear of CPS. The best defense is a calm verification processrespectful, firm, and documented.

If you remember nothing else, remember this: you’re allowed to slow the moment down. Verify identity. Ask for details. Call the official number. And if the contact is legitimate, treat it like a process you can navigateone step at a time.

Experiences families share about pregnancy-era child welfare scares (added perspective)

Because every state and every situation is different, people’s “CPS during pregnancy” stories can sound like they happened on different planets. Still, there are common experiences that show up again and againespecially in online support groups and parent communities. Here are examples of what people often describe, and what they learned from it.

1) “We thought we were being investigated, but it was really discharge planning.”

One common story starts in the hospital, not at home. Parents say a nurse mentioned “social work,” and suddenly their brain filled in the worst possible ending: foster care. In reality, the meeting was about resourcesWIC enrollment, a safe sleep setup, transportation to pediatric visits, or mental health support. The lesson families often share: ask exactly what the meeting is for and what the next step is. Words like “assessment,” “plan,” and “notification” can sound scary, but they don’t always mean “accusation.”

2) “A rumor turned into a report, and we got pulled into proving a negative.”

Some parents describe referrals that started with a neighbor, a family conflict, or a messy breakupsomeone reported drug use, violence, or “unsafe people around the baby.” Even when the report was unfounded, the family still felt the stress of being watched. People who’ve been through this often recommend keeping a simple paper trail: prenatal appointment summaries, a safe-sleep photo setup (crib/bassinet), and a list of who lives in the home. Not because families should have to audition for parenthood, but because documentation can shorten confusion when someone else’s story is driving the narrative.

3) “We met a great caseworker… and then the system changed midstream.”

Another frequently shared experience is that the individual professionals can be thoughtful and supportive, but the process can still feel chaotic. A caseworker might explain everything clearlythen rotate out, go on leave, or get reassigned, and the family has to retell their story to someone new. Families often say it helped to keep a one-page “snapshot” ready: names, dates, pediatrician contact, any services already in place, and what the family has already completed. It turns emotional chaos into something closer to a checklist (not funbut survivable).

4) “The scariest moment was the not-knowing: is this real, and who do we call?”

This is where the viral “fake caseworker” twist hits hardest. Parents describe feeling trapped between two fears: ignoring a real agency contact and making things worse, or trusting a stranger and exposing themselves to a scam. People who’ve navigated impersonation scares usually say the same thing: verification is everything. They recommend looking up the agency number themselves, asking for ID, and refusing to share personal data until they’ve confirmed the person’s identity. Some families also say they started using a doorbell camera and keeping doors locked during unexpected visitsnot out of paranoia, but because it gives them time to think.

5) “We learned to advocate without turning the interaction into a fight.”

Probably the most useful shared lesson is tone. Families who felt they had the best outcomes often describe being calm, polite, and firmasking questions, requesting supervisors when needed, and setting boundaries without escalating. They also talk about finding support early: a trusted family member at meetings, a doula or patient advocate in the hospital, legal advice when the situation felt serious, and mental health support to manage the stress. The common thread isn’t that the system is always fair (it isn’t), but that preparation and composure can reduce the chance of misunderstandings snowballing.

If you’re reading this because the idea of “child services investigating a fetus” made your stomach drop, you’re not alone. The practical takeaway from real-world experiences is simple: verify first, document second, and don’t let fear rush you into unsafe decisions.