Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Event Schema” Actually Means (and Why You Should Care)

- Where Userpilot’s Event Schema Fits In

- Userpilot Import Event Schema: The Four Core Event Types

- Userpilot Export Event Schema: What You Get Back (and How to Use It)

- How to Design an Event Schema That Doesn’t Collapse Under Its Own Weight

- Schema Governance: How to Keep Your Data From Going Feral

- A Simple Event Schema Blueprint You Can Steal (Politely)

- GA4, Parameters, and the “Events With Properties” Worldview

- Common Mistakes That Break Event Schemas (So You Don’t Have to)

- Conclusion: A Clean Event Schema Is an Unfair Advantage

- Experiences and Lessons Teams Commonly Learn About Event Schemas (Field Notes)

If your product analytics feels like a closet where every hanger is labeled “stuff,” you don’t have an analytics problemyou have a schema problem.

An event schema is the difference between “We think users are dropping off somewhere around onboarding-ish?” and

“Step 3 of the checklist is the villain, and it’s wearing a top hat.”

This guide breaks down what an event schema is, how it shows up inside the Userpilot Knowledge Base (especially the Import/Export

schema you’ll see in Userpilot’s developer docs), and how to design one that stays readable even after your product evolves, your team grows,

and somebody inevitably tries to name an event ButtonClicked_FINAL_v3.

What “Event Schema” Actually Means (and Why You Should Care)

In plain English: an event schema is the agreed-upon structure for the behavioral data you trackwhat fields an event contains, what’s required,

what’s optional, and what values are considered valid. It’s the blueprint that keeps your tracking consistent across:

onboarding flows, feature adoption, NPS surveys, checklists, and everything else your product throws at real human beings.

A strong schema answers questions like:

- What is the event called? (and is it named consistently?)

- Who did it? (user identity, company identity, anonymous vs. logged in)

- When did it happen? (timestamp precision and timezone expectations)

- Where did it happen? (page, host, path, device)

- What context matters? (properties/metadata that make the event usable for analysis)

Without a schema, dashboards become expensive guessing games. You end up with “sign_up”, “Sign Up”, “signup”, and “user_signup”

all meaning the same thingexcept your analytics tool treats them as four different events and your stakeholders treat them as four different truths.

That’s not “data-driven.” That’s “data-driven-to-confusion.”

Where Userpilot’s Event Schema Fits In

Userpilot is often used to power and measure product adoption: onboarding flows, in-app experiences, checklists, surveys, NPS,

resource center usage, and feature engagement. To make that measurable at scale, Userpilot defines a consistent event structure for:

importing events (bringing data in) and exporting events (sending data out for analytics, BI, warehousing, or governance).

In practice, you’ll typically interact with Userpilot’s event schema in two ways:

- Import API (Bulk Import): you upload events in a defined format so Userpilot can store and use them.

- Export (Bulk Export / Data Sync): you retrieve Userpilot events with a defined structure to analyze elsewhere.

Userpilot Import Event Schema: The Four Core Event Types

Userpilot’s Import schema supports a small set of foundational event types. Think of these as the “four horsepeople of clean data”:

identity, company identity, page views, and custom tracking.

1) Identify User

The identify_user event type is used to identify a user and/or update user attributes.

In schema terms, this typically includes:

event_type(must beidentify_user)user_id(your unique user identifier)metadata(key-value user attributes like name, email, plan, role)source(where the data came from)inserted_at(timestamp of when it was recorded)

Schema tip: Treat user attributes like a closet inventoryuse clear labels, keep it consistent, and don’t shove random one-off facts

in there unless you’ll actually use them later. “favorite_pizza_topping” is fun. “favorite_pizza_topping_at_the_time_of_signup” is a cry for help.

2) Identify Company

The identify_company event type identifies or updates company/account attributes (great for B2B products).

Expect fields like:

event_type(must beidentify_company)company_id(unique account identifier)metadata(industry, plan tier, ARR band, seats, region, etc.)source,inserted_at

Practical example: If your product has “workspaces,” your company_id might map to workspace ID. If it has “accounts,” map it to account ID.

The important thing is that the identifier is stable and consistent across systems.

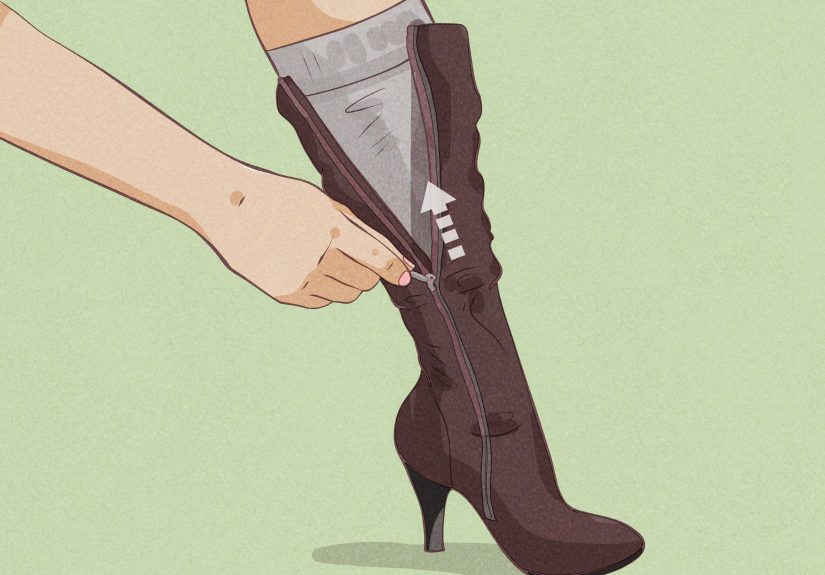

3) Page View

The page_view event type logs a user viewing a page (commonly used for web-based products).

Typical schema fields include:

event_type(must bepage_view)user_idhostnameandpathnamesource,inserted_at

Schema tip: Decide early how you’ll represent “where” the event happened. If you mix full URLs sometimes and only paths other times,

your funnels will look like abstract art. Beautiful, but not actionable.

4) Track (Custom Event)

The track event type is your flexible “custom action” recordclicks, upgrades, completed steps, feature usage, you name it.

Most schemas require:

event_type(must betrack)user_idevent_name(the name of the action, likeaccount_upgraded)metadata(optional but strongly recommended for context)source,inserted_at

Good tracking isn’t “more events.” It’s the right events with the right context.

A single event like plan_changed with properties (old_plan, new_plan, billing_period) is often more useful than

five different events that differ only by name.

Userpilot Export Event Schema: What You Get Back (and How to Use It)

Exported Userpilot event data is structured so analysts and engineers can use it in warehousing and reporting. You’ll see common fields that describe:

the app, the event type, the event name, who did it, where it happened, and a metadata object that varies by event type.

At a high level, exported events include fields like:

app_token, event_type, event_name, user_id, company_id, source,

inserted_at, hostname, pathname, device/browser details, and metadata.

One important nuance: the meaning of event_name depends on event_type.

In the exported schema, some event types leave the name empty, while others populate it with a meaningful identifier.

That’s a schema design choice that keeps “structured” events clean and puts “custom” meaning where it belongs.

Interaction Events: When “event_name” Encodes the Story

Userpilot exports can include interaction events that represent engagement with in-app experiences

(like checklists, resource center articles, surveys, NPS, flows, and experiments). For these, the event name can follow a structured pattern:

This style is surprisingly handy: it’s compact, readable, and easy to group by entity type (checklist) or status (SEEN, ENGAGED, etc.).

Just don’t forget: if you want deeper analysis, the “details” still belong in properties/attributes, not in an endlessly growing event name.

How to Design an Event Schema That Doesn’t Collapse Under Its Own Weight

A schema isn’t just a list of eventsit’s a language. And like any language, it needs grammar, vocabulary, and a rule against inventing new verbs

mid-sentence because someone “felt inspired” during a sprint.

Pick a Naming Convention and Enforce It

The best naming convention is the one your team will actually follow. The point is consistency:

choose casing, choose structure, document it, and don’t let it drift.

- Structure: Many teams use an “Object + Action” format (example:

Blog Post Readorpage_vieweddepending on casing rules). - Casing: Some ecosystems prefer Title Case for event names and snake_case for properties; others prefer all-lowercase + underscores.

- Readability: Humans should understand event names without decoding a secret cipher.

If you’re building a schema that will be used outside your product team (hello, marketing ops and customer success),

prefer names that are descriptive and stable. The goal is discoverability: someone should be able to find the right event without Slack archaeology.

Don’t Put Variable Data in the Event Name

Dynamic event names are the analytics equivalent of labeling every moving box “misc.” You can do it. You will regret it.

Keep the event name stable and move the variability into properties.

Bad: Purchased Plan - Premium Annual

Better: plan_purchased with plan_tier=premium, billing_period=annual

Use Properties (Metadata) to Capture Context

A good event name tells you what happened. Properties tell you how, where, which version, what plan, what device, and

why you should care.

Here’s a practical “Userpilot-ish” custom track event example you can adapt:

This stays clean because the event name is stable, and the properties do the heavy lifting.

If the business later asks, “Which upgrades came from the paywall modal?” you already have the answer.

If they ask, “Which upgrades were annual?” also answered. If they ask, “Which upgrades happened on Tuesdays during a full moon?” you can politely log off.

Schema Governance: How to Keep Your Data From Going Feral

Even the best schema can be sabotaged by “just this one quick tracking tweak.” Multiply that by 12 engineers and 6 releases, and your event catalog becomes

a haunted mansion: lots of rooms, strange noises, nobody knows what’s inside.

Tracking Plans and Validation Rules

Data governance tools (often called tracking plans) help you define what events are allowed, what properties they must include,

and what data types are validthen flag or block events that don’t comply.

This is especially useful when events fan out to many destinations (warehouse, marketing automation, BI dashboards).

A governance mindset typically includes:

- Approved event list: what can be sent, and from where

- Required properties: what must exist (and the expected type)

- Versioning: how you evolve your schema without breaking dashboards

- Observability: how you detect drift (new events, renamed fields, null explosions)

Enforcement Beats “Please Follow the Doc”

Documentation is necessary. Enforcement is magical. When your tooling nudges people into compliant naming and schema structure,

you spend less time cleaning data and more time using it.

A Simple Event Schema Blueprint You Can Steal (Politely)

Here’s a practical mini-schema for a SaaS onboarding + adoption setup, designed to work nicely with Userpilot-style in-app experiences.

The goal is to cover identity, navigation, onboarding progress, and activation signalswithout tracking every blink.

Core Events

| Event Type | Event Name | Required Properties (Examples) | Why It Exists |

|---|---|---|---|

| identify_user | (empty) | metadata.email, metadata.role, metadata.signup_date | Connect behavior to a real user profile |

| identify_company | (empty) | metadata.plan_tier, metadata.seats, metadata.industry | Enable B2B segmentation and account-level adoption |

| page_view | (empty) | hostname, pathname | Understand navigation patterns and funnel steps |

| track | onboarding_step_completed | step_id, step_name, checklist_id | Measure onboarding completion and drop-off points |

| track | key_feature_used | feature_id, feature_name, context | Define activation and adoption signals |

| track | account_upgraded | old_plan, new_plan, billing_period | Connect product usage to revenue outcomes |

Notice what’s missing: fifty flavors of button clicks. You can track button clicks, but you should do it intentionally:

(1) when a click represents a meaningful product decision, or (2) when it’s part of a measurable funnel step.

Otherwise your analytics will become a documentary called “Humans Clicking Things: The Extended Cut.”

GA4, Parameters, and the “Events With Properties” Worldview

Modern analytics ecosystems increasingly treat events as the core unit of measurement, with parameters/properties attached for context.

That pattern shows up in tools like GA4, where recommended events come with prescribed parameters and custom parameters add richness when configured correctly.

Translation: events tell you what happened; parameters tell you the details.

If you’ve ever tried to understand “purchase” events without item details, you already know why that matters.

Common Mistakes That Break Event Schemas (So You Don’t Have to)

1) Inconsistent naming (the silent dashboard killer)

Inconsistent names won’t “sort themselves out.” They multiply. And the more your product grows, the more expensive cleanup becomes.

Treat naming consistency like you treat authentication: you don’t improvise it differently on every page.

2) Tracking the same action under multiple names

If “Invite Sent” and “User Invited” are the same thing, pick one. If they’re different, define the difference in writing and in properties.

Ambiguity makes funnels unreliable and trust evaporates fast.

3) Overloading event names with details

Put details in properties. Keep event names stable. Future-you will thank present-you with a gift basket of not having to rebuild dashboards.

4) No ownership or review process

Someone needs to own the schema: approve new events, maintain definitions, and prune what’s obsolete.

“Everyone owns it” often means “nobody owns it,” which is how you end up with signup and sign_up both powering executive reports.

Conclusion: A Clean Event Schema Is an Unfair Advantage

When your event schema is clear, consistent, and governed, analytics stops being a messy back-office chore and becomes a product superpower.

You can measure onboarding performance, feature adoption, experimentation outcomes, and customer sentiment without translating 47 event names into one meaning.

The Userpilot Event Schema (especially across Import/Export) gives you a strong foundation: identity events, page views, custom tracking,

and structured interaction events for in-app experiences. Combine that with a disciplined naming convention, smart use of metadata,

and lightweight governance, and you’ll have a dataset your whole organization can trust.

And if anyone tries to introduce Clicked Button (Homepage, Tuesday) as a new event name… you have my permission to send them this article

and a friendly reminder that properties exist for a reason.

Experiences and Lessons Teams Commonly Learn About Event Schemas (Field Notes)

The most useful “experience” with event schemas usually comes from the moment something breakslike a dashboard that suddenly shows a 40% drop in signups,

and everyone panics… only to discover the signup event was renamed during a “tiny refactor” that wasn’t documented. Teams that build strong schemas

early tend to have fewer of these adrenaline-fueled mysteries.

One recurring lesson: schemas fail socially before they fail technically. The data pipeline may be perfect, but if engineers and non-technical

teammates can’t agree on event definitions, your analytics becomes a debate club. Teams that win here do three small things consistently:

(1) write one clear definition for each event, (2) keep examples right next to the definition, and (3) appoint an owner who can say “yes,” “no,”

or “not like thattry again.”

Another lesson is about the seductive trap of “tracking everything.” Early on, it feels safe: more data must mean more insight, right?

In reality, over-tracking often creates noise that hides signal. The teams that get real value from Userpilot-style adoption analytics typically track:

meaningful onboarding milestones, activation actions (your “aha” moments), and a handful of friction signals (errors, dismissals, drop-offs).

They don’t track every hover, every scroll, and every “user blinked at a tooltip” unless it supports a specific decision they plan to make.

Teams also learn (sometimes the hard way) that properties are where analysis lives. A clean event name gets you into the right neighborhood,

but properties get you to the exact house. If “Account Upgraded” doesn’t include old/new plan, billing period, and trigger context, you’ll spend weeks

reverse-engineering what happened. With good properties, you can answer rich questions quickly: “Did upgrades increase after we changed the paywall copy?”

“Do annual upgrades happen more on desktop?” “Which onboarding path correlates with Pro conversions?”

Governance is another theme. In growing organizations, schema drift is normal: new features ship, teams change, experiments come and go.

The teams that stay sane adopt light governance earlyoften a tracking plan or at least a checklist for new events:

Is the event name consistent? Is the action meaningful? Are required properties included? Is it documented? Is it redundant with something else?

You don’t need bureaucracy; you need a speed bump that prevents the worst mistakes.

Finally, a very practical “real world” lesson: make your schema usable for people who didn’t build it. Analysts rotate. PMs change teams.

Customer success and marketing show up with questions. If your event names read like internal jokes or your properties are cryptic abbreviations,

you’ll bottleneck every question through the two people who remember what anything means. Teams that scale self-serve analytics tend to prioritize

human-readable naming, consistent casing, and short examples. The payoff is huge: faster insight, fewer meetings, and dashboards that don’t require a

translator.

In other words: the best event schema is the one that makes the “What does this mean?” question rareand makes the “What should we do next?”

question easy.