Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is For the Love of Nancy?

- Why It Landed So Hard in the ’90s (and Still Does)

- The Nancy Scorecard: Ranked Highlights (Best to “Needs Work”)

- #1: Tracey Gold’s Performance (The Anchor That Holds the Whole Film)

- #2: The Family Perspective (Because Eating Disorders Don’t Only “Happen” to One Person)

- #3: Showing the Emotional Spiral (Not Just the Surface Behavior)

- #4: The “This Is Serious” Tone (No Wink, No Nudge, No Cute Moral)

- #5: A Useful Conversation Starter (Even When It’s Not a Perfect Film)

- #6: The Pacing and Timeline Jumps (The Film’s Most Common Critique)

- #7: The “TV Movie Wrap-Up” Instinct (A Little Too Neat, A Little Too Fast)

- #8: The Era-Specific Lens (1994 Culture Shows Up Like an Uninvited Guest)

- My Opinions: What the Film Gets Right About Eating Disorders

- My Opinions: Where the Film Struggles (and Why That Matters)

- Where It Ranks in the “Issue Movie” Hall of Fame

- How to Watch It Today Without Missing the Point

- Real-World Experiences Around For the Love of Nancy (500+ Words)

- Conclusion

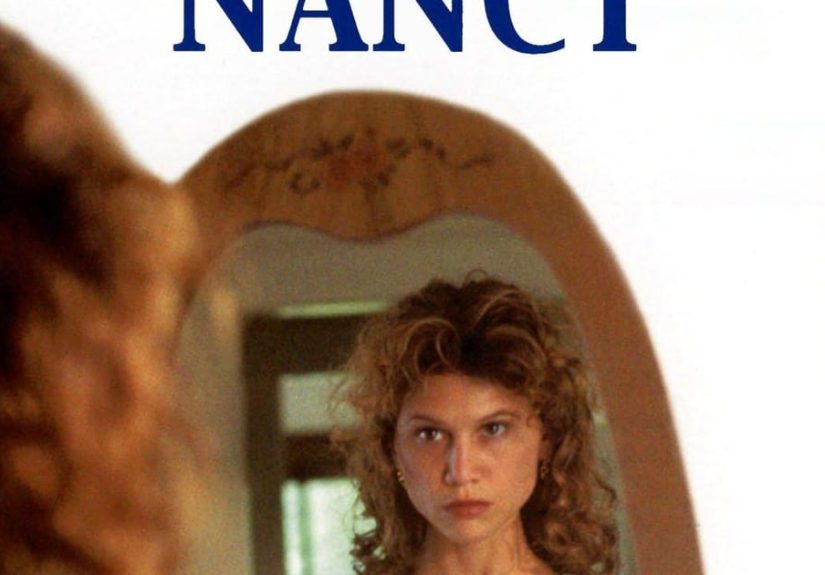

Some movies arrive with fireworks and fanfare. Others show up like a concerned neighbor knocking at your door at 9 p.m. on a Sunday: no glitter, no cape, just a

serious message and a very specific time slot. For the Love of Nancy (1994) is firmly in that second categorya made-for-TV drama that aired on ABC as part

of its Sunday night movie lineup, starring Tracey Gold and tackling anorexia nervosa at a time when prime-time TV rarely named eating disorders out loud.

Today, the movie lives in that special pop-culture corner reserved for “issue films” that people remember vividly even if they haven’t watched them since

the era of VHS rewinds and commercials that lasted longer than a modern TikTok career. This article is a rankings-and-opinions deep dive: what the film does

exceptionally well, what feels dated, where it lands emotionally, and why it still gets discussed in classrooms, families, and online review threads decades later.

(Spoiler: it’s not because anyone misses 1994 hair.)

What Is For the Love of Nancy?

For the Love of Nancy is a 1994 American television drama film directed by Paul Schneider and written by Carol Evan McKeand and Nigel McKeand.

It stars Tracey Gold as Nancy Walsh, a recent high school graduate heading into a new stage of life. Nancy’s shifting sense of control, identity, and self-worth

begins to spiral into an eating disorder, leaving her family scrambling to understand what’s happening and how to help.

The supporting cast includes heavy hitters: Jill Clayburgh and William Devane as Nancy’s parents, plus Mark-Paul Gosselaar and Cameron Bancroft in key family roles.

It’s a familiar made-for-TV setupdomestic scenes, rising tension, emotional confrontationsbut the subject matter is anything but comfortable, and that’s the point.

Why It Landed So Hard in the ’90s (and Still Does)

In the mid-1990s, the culture around bodies and “thinness” was loud, relentless, and often treated like harmless comedyespecially for young women in entertainment.

Tracey Gold has spoken publicly about the pressures and jokes about her body during her years on television and how that environment contributed to her eating disorder.

That context matters because her performance in For the Love of Nancy doesn’t play like a detached reenactment; it plays like someone who understands the

emotional logic of the illness from the inside.

The film also arrived when public-facing conversations about eating disorders were far less common. Major health organizations emphasize that eating disorders are

serious illnessescomplex, multifactorial, and potentially life-threateningnot “phases” or vanity projects. Watching the film now, you can feel it trying to pull

the topic out of whispers and into daylight, using the most powerful megaphone of the era: network TV.

The Nancy Scorecard: Ranked Highlights (Best to “Needs Work”)

Rankings are subjective, but this movie practically invites a scorecard. Here’s a ranked list of the film’s most effective elementsfollowed by the parts that,

in hindsight, show their made-for-TV seams.

#1: Tracey Gold’s Performance (The Anchor That Holds the Whole Film)

The film’s biggest strength is the lead performance. Gold portrays Nancy’s inner tensionfear, denial, stubbornness, vulnerabilitywithout turning her into a

stereotype. Even when the script leans dramatic (because it’s a TV movie, and subtlety sometimes missed the bus), her performance keeps the story grounded.

#2: The Family Perspective (Because Eating Disorders Don’t Only “Happen” to One Person)

One reason For the Love of Nancy stuck with viewers is that it doesn’t frame anorexia as a solo storyline. The film is obsessedappropriatelywith what it

feels like for a family to watch someone they love change in confusing, frightening ways. That aligns with what many clinical resources describe: families often

notice withdrawal, secrecy, and escalating distress before a person recognizes (or admits) there’s a problem.

#3: Showing the Emotional Spiral (Not Just the Surface Behavior)

When the movie works, it’s because it hints at the psychological “why” underneath the visible changes: anxiety about the future, shifting identity, a craving for

control when life feels unsteady. Modern clinical guidance emphasizes that eating disorders are not simply about food; they involve a complicated mix of emotional,

biological, and social factors.

#4: The “This Is Serious” Tone (No Wink, No Nudge, No Cute Moral)

Some issue movies try to soften the message with comedy or neat resolutions. This film doesn’t. Trade coverage at the time noted both its intent to raise awareness

and its tendency to lean into familiar TV-movie storytelling. But the core decisionto treat anorexia as urgent and realstill feels right.

#5: A Useful Conversation Starter (Even When It’s Not a Perfect Film)

The movie’s educational value is part of its legacy. Whether you’re a parent, a teacher, or a viewer who stumbled on it during a rerun, it prompts questions:

What are warning signs? When do you step in? How do you help without turning every meal into a battleground?

#6: The Pacing and Timeline Jumps (The Film’s Most Common Critique)

Viewer commentary over the years has frequently pointed out abrupt transitionsscenes that end and restart later with emotional “bridges” missing. That can make

the story feel choppy, and it sometimes reduces complex change into quick beats: problem, escalation, confrontation, breakthrough. Real recovery rarely moves in

such a straight line.

#7: The “TV Movie Wrap-Up” Instinct (A Little Too Neat, A Little Too Fast)

The film gestures toward hope and recovery, which is important, but it sometimes collapses the long, uneven reality of treatment into a more compressed narrative

arc. Many modern guidelines describe treatment as individualized and often multi-layeredmedical monitoring, nutritional rehabilitation, psychotherapy, and ongoing

supportespecially when health is at risk.

#8: The Era-Specific Lens (1994 Culture Shows Up Like an Uninvited Guest)

This isn’t a flaw as much as a historical reality: the movie reflects how the ’90s talked about bodies, control, and “discipline.” Some dialogue choices can land

awkwardly today, partly because we now have better language around mental health, stigma, and compassionate intervention.

My Opinions: What the Film Gets Right About Eating Disorders

It Treats Anorexia as an Illness, Not a Personality Quirk

The film refuses the lazy trope that eating disorders are just “teen drama” or attention-seeking. Medical resources describe anorexia nervosa as a serious mental

health condition with real physical risks, and the film’s seriousness matches that reality. It doesn’t glamorize the disorder; it portrays it as isolating and

consuming.

It Highlights Warning Signs People Actually Notice

Many educational resources list warning signs like preoccupation with food/weight, changes in social behavior, avoidance, secrecy, and increased anxiety around

eating situations. The movie focuses heavily on those relational signalshow someone pulls away, how conversations become tense, how denial becomes a wall.

It Shows the Family’s Confusion (and That’s Realistic)

Families often start from a place of “Is something wrong?” rather than immediate certainty. The film captures that slow realization: small concerns pile up, then

the situation becomes impossible to ignore. That progression mirrors what many parents and loved ones describean unsettling shift that’s hard to name at first.

My Opinions: Where the Film Struggles (and Why That Matters)

It Sometimes Trades Complexity for Drama

The TV-movie format loves big moments: a confrontation, a breakdown, a dramatic turning point. But eating disorders are often quieter and more repetitive than a

screenplay wants. The film can feel like it’s racing toward a “lesson,” and that can unintentionally understate how long recovery takes and how many setbacks are

normal.

It Doesn’t Always Explain the “How” of Healing

To be fair, no single movie can serve as a treatment manual (and it shouldn’t). Still, some critics at the time argued the story tiptoed around the practical

details of recovery and leaned into familiar moral beats. Modern clinical guidance emphasizes evidence-based care and sustained support; a film can’t replicate

that, but it can avoid making recovery look like a simple switch flip.

It Risks a Single-Story Impression

Eating disorders affect people of many genders, ages, body sizes, and backgrounds. The film tells one story in one familypowerful, yes, but not universal.

Today, it’s helpful to watch it as a depiction, not the depiction, and pair it with broader, up-to-date education about eating disorders.

Where It Ranks in the “Issue Movie” Hall of Fame

If we’re ranking For the Love of Nancy among made-for-TV “issue” dramas, it lands high in cultural impact and conversation value. It may not be a perfect

film in structure, but it’s memorable because it meets viewers where they are: at home, in a family setting, watching a story that can be difficult to discuss

face-to-face.

It also ranks well in sincerity. Even when the storytelling gets a little clunky, the movie’s intention is clear: eating disorders are serious, families need help,

and silence makes everything worse. That message lines up with major health organizations that frame eating disorders as treatable illnesses where early recognition

and professional care matter.

How to Watch It Today Without Missing the Point

1) Watch With Context, Not Just Nostalgia

If you’re revisiting the movie, treat it like a time capsule and a conversation starter. Some scenes are very “1994 network drama,” but the core emotions

still track: fear, denial, worry, love, frustration, and the exhausting search for the right words.

2) Focus on the Relationships, Not the Specifics

If you’re watching with teens or students, keep the discussion centered on feelings, communication, and support rather than zooming in on body talk. Many health

experts recommend avoiding appearance-based comments and instead emphasizing health, coping skills, and reaching out for help.

3) Remember: A Movie Is Not Medical Advice

The film can open a door, but reliable medical organizations stress that diagnosis and treatment should involve qualified professionals. If someone is struggling,

the best next step is to talk to a trusted adult and seek professional support.

Real-World Experiences Around For the Love of Nancy (500+ Words)

The most interesting thing about For the Love of Nancy isn’t just what’s on screenit’s what happens after the credits, when viewers start

talking. Over the years, people have described watching it in wildly different contexts: health class on a rolling TV cart, a living-room “family movie night”

that suddenly turned serious, a late-night cable rerun when they were too young to fully name what they were feeling. Those viewing experiences vary, but the

emotional aftermath often rhymes: silence, then questions, then a slow realization that “this is closer to real life than I thought.”

Educators and counselors have often treated films like this as discussion toolsnot because a TV movie is the gold standard of mental health education, but because

storytelling lowers defenses. A lecture can feel like a spotlight. A movie feels like sitting beside someone, looking at the same thing, and finally having

permission to say, “Okay… can we talk about that?” In that sense, For the Love of Nancy can function like a social bridge: it provides a shared reference

point so students or family members don’t have to start with personal confessions. They can start with the safer line: “Nancy seemed really anxious,” or “Her

parents didn’t know what to do,” and thenonly if they wantconnect it to real life.

Viewers who have lived experience with eating disorders sometimes describe a different reaction: a mix of recognition and frustration. Recognition, because the

isolation and denial feel familiar. Frustration, because movies tend to compress time and simplify recovery into a tidy arc. That tension can actually be useful

in a guided conversation: “What felt accurate?” and “What felt too neat?” Both answers can be true, and both can help people build a more realistic understanding

that recovery is often uneven and support needs to be ongoing.

Families watching together often report the “wrong words, right intentions” phenomenon. A parent may relate to the fear and helplessness, while a teen may relate

to the pressure, the anxiety, or the sense that everything is being watched. Sometimes the movie sparks a meaningful talk. Sometimes it sparks conflict. And

sometimes it sparks nothing at all in the momentjust a lingering thought that returns later, when someone notices a friend withdrawing, or when a comment about

bodies hits differently than it used to. Not every “teachable moment” arrives on schedule; some show up weeks later at the most random time, like when you’re

folding laundry and your brain suddenly decides, “Hey, remember that movie? Let’s process that now.”

Online, long-running review threads show another kind of experience: communal memory. People debate whether the pacing works, whether the timeline jumps weaken the

story, whether the adults in the movie acted fast enough, whether the ending feels earned. But beneath the film-nerd arguments, there’s often something gentler:

a shared agreement that the movie mattered. It made eating disorders harder to ignore. It framed them as serious. It gave viewers language when they didn’t have

it. And for some people, it nudged themdirectly or indirectlytoward seeking help or encouraging someone else to do so.

If you’re using For the Love of Nancy as a conversation starter today, one of the most practical “experience-based” lessons is this: don’t make the

conversation about bodies. Make it about stress, control, coping, and support. Ask what characters needed emotionally. Ask what a helpful response could look like.

Ask how you’d want a friend to talk to you if you were struggling. That’s where the movie’s lasting value livesnot in a perfect plot, but in the human reactions

it provokes and the discussions it can unlock.

Conclusion

For the Love of Nancy isn’t flawless, but it is memorableand that’s a kind of power. Ranked as a cultural conversation piece, it scores high: a strong lead

performance, a family-focused lens, and a clear insistence that eating disorders are serious illnesses deserving empathy and professional care. Its weaknesseschoppy

pacing, simplified recovery beats, a very 1990s storytelling styleare real, but they don’t erase its value. If anything, they make it even more important to

watch with context, pair it with accurate education, and use it as a starting point for better, kinder conversations today.