Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “a very simple program” actually means

- Step 1: Install Python (and avoid the “wrong Python” trap)

- Step 2: Pick a place to write code (the “where do I type?” problem)

- Step 3: Write your first Python script (Hello, World… and hello, confidence)

- Step 4: Make it interactive with input()

- Step 5: Add a tiny bit of logic (because “if” is where programs become programs)

- Step 6: Turn it into a “real” mini program with main() and a main guard

- Step 7: Add one useful feature (a tiny calculator)

- Step 8 (Optional but smart): Use a virtual environment so projects don’t fight

- Step 9: Save your script like a mini-project (so you can share it later)

- Troubleshooting: the most common beginner snags (and how to fix them)

- What to build next (still simple, slightly cooler)

- Beginner Experiences: What People Learn the Hard Way (and Laugh About Later)

- Conclusion

Python is one of the friendliest ways to tell a computer what to dowithout having to speak in beeps, boops, or

ancient runes. If you’re brand new, your first goal isn’t to build the next social network. It’s to build a tiny

program that runs, prints something, and makes you think: “Oh. I can do this.”

This guide walks you through creating a very simple Python program step by step, with clear examples

and a few beginner-proof habits that will save your future self a surprising amount of stress. (Future you is picky.

Present you is brave. Let’s help them get along.)

What “a very simple program” actually means

A “simple program” doesn’t mean “toy” or “pointless.” It means:

- One file (usually

.py) - A clear goal (print a message, ask a question, do a small calculation)

- No complicated setup (no databases, no frameworks, no 47 browser tabs)

- Easy to run from your computer

Once you can reliably create and run a small script, you can scale upbecause “bigger programs” are mostly just

“small programs” that learned how to live together in folders.

Step 1: Install Python (and avoid the “wrong Python” trap)

Before you write code, make sure your computer can run it. Install a modern Python 3 version from the official

source. After installing, verify it works by opening a terminal (Command Prompt on Windows, Terminal on macOS/Linux)

and checking your version.

Check your Python version

If that command doesn’t work, try:

If you see a Python 3.x version, you’re in business. If you see “command not found,” you likely need to finish

installation or adjust your PATH settings. (Translation: your computer doesn’t know where Python lives yet.)

Step 2: Pick a place to write code (the “where do I type?” problem)

You have options. The best beginner choice is the one that feels easiest to use today.

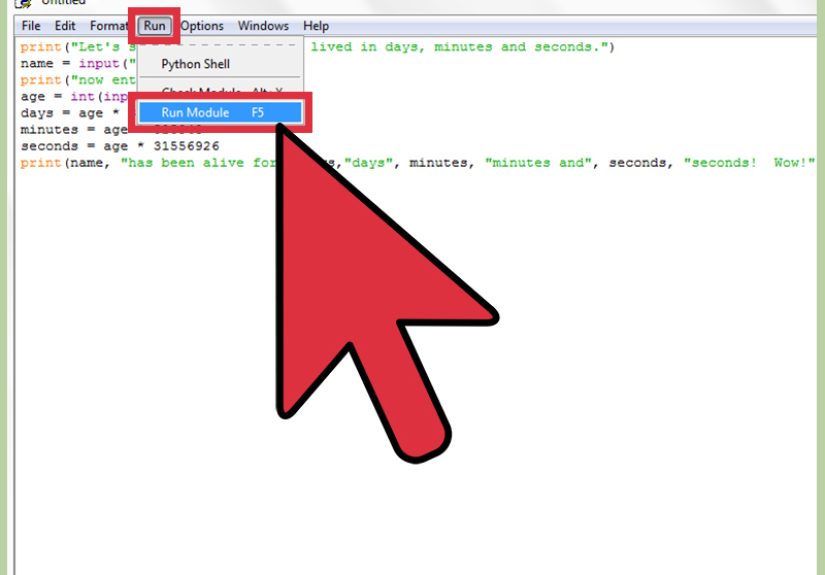

Option A: IDLE (simple, built-in)

Python often includes IDLE, a basic editor that’s great for learning. It won’t overwhelm you with

features. It also won’t judge your variable names. (Unlike your future coworkers.)

Option B: Visual Studio Code (popular, flexible)

VS Code is a lightweight editor that can run and debug Python with an extension. It’s great if you

want nicer formatting, helpful hints, and a smoother “real project” workflow.

Option C: Any text editor + terminal (minimalist mode)

You can write Python in any editor as long as you save the file with a .py extension and run it from a terminal.

This is the “I like simple tools” approach.

Step 3: Write your first Python script (Hello, World… and hello, confidence)

Create a new folder for your project. Name it something like python-practice. Inside it, create a file called

hello.py. (Yes, you can name it something else, but let’s not fight tradition on Day 1.)

Your first program: hello.py

Run it

Open your terminal, navigate into the folder where hello.py is saved, and run:

You should see:

Congratulations. You just made a computer follow your instructions. This is basically wizardry, but with fewer robes.

Step 4: Make it interactive with input()

Printing is nice, but programs get fun when they respond to the user. Python’s input() function lets you ask

a question and capture what the user types.

A friendly greeter

That f"..." string is called an f-string. It’s an easy, readable way to insert values into text.

Run it

Example interaction:

Step 5: Add a tiny bit of logic (because “if” is where programs become programs)

The magic of code is decision-making. In Python, decisions often start with if.

A polite program with manners

Notice the indentation. Python uses indentation to define blocks of code. If you mix tabs and spaces, Python will

absolutely notice and will respond with a dramatic error. Use spaces consistently (many editors do this automatically).

Step 6: Turn it into a “real” mini program with main() and a main guard

As your scripts grow, it’s a good habit to put your “start here” code inside a function called main().

Then you use a common pattern so the script runs when executed directlybut doesn’t auto-run if it’s imported elsewhere.

A clean starter template

Think of if __name__ == "__main__": as a bouncer at the door:

“Are you running this file directly?” If yes, main() gets in. If not, it stays calm and does nothing.

Step 7: Add one useful feature (a tiny calculator)

Let’s build a small program that asks for two numbers and an operator, then prints the result. This includes:

input, type conversion, if/elif, and a dash of error handling.

calculator.py

Run it

This is a “very simple program,” but it already demonstrates the core skills you’ll use in bigger projects.

Step 8 (Optional but smart): Use a virtual environment so projects don’t fight

When you start installing packages, it’s best to keep each project’s dependencies separate. A

virtual environment is an isolated folder that holds its own Python packages.

Create and activate a virtual environment (venv)

macOS/Linux:

Windows (PowerShell):

Once activated, installing packages with pip installs them into that environment, not your whole computer.

If you’re not installing anything yet, you can skip this stepbut it’s a great habit for real projects.

Step 9: Save your script like a mini-project (so you can share it later)

Even tiny programs benefit from a little structure. Here’s a clean starter folder layout:

What to put in a README (keep it short)

- What the program does (one sentence)

- How to run it (the exact command)

- Any requirements (Python 3.x, optional packages)

This takes five minutes and makes your work look instantly more professional.

Troubleshooting: the most common beginner snags (and how to fix them)

1) “Python is not recognized” / “command not found”

Python isn’t installed, or your terminal can’t find it. Reinstall from the official source and ensure Python is added to PATH.

On some systems, you may need to use python3 instead of python.

2) “No such file or directory”

You’re running the command from the wrong folder. In your terminal, navigate to the folder where the file is saved,

or provide the full path.

3) IndentationError

Python cares about indentation. Make sure your indented blocks are consistent, and don’t mix tabs and spaces.

4) SyntaxError near quotes or parentheses

Check that every opening quote has a closing quote, and every ( has a matching ).

Most editors can help you spot mismatched pairs.

5) ValueError when converting input

If you do float(input(...)) and the user types “banana,” Python can’t convert it. Use try/except

like the calculator example.

6) “ModuleNotFoundError” after installing packages

Usually, you installed the package in a different environment than the one you’re running. Activate your virtual environment,

then install again.

7) The program runs but “does nothing”

The file might be empty, not saved, or you’re running a different file than you think. Add a print("Running...")

at the top to confirm the correct script is executing.

What to build next (still simple, slightly cooler)

If you want to level up without drowning in complexity, try one of these:

- Dice roller: generate random numbers and print results

- Tip calculator: totals, percentages, formatting

- Guessing game: loops + comparisons

- Simple file note saver: write lines to a text file

Each is “simple,” but each teaches a real skill you’ll reuse.

Beginner Experiences: What People Learn the Hard Way (and Laugh About Later)

When you’re learning how to create a very simple program in Python, the code is only half the story. The other half

is the collection of tiny, normal, absolutely-unavoidable moments that make you feel like your computer is trolling you.

The good news? Nearly everyone goes through the same stuffand it’s usually fixable in minutes once you know the pattern.

One of the most common early “experiences” is the wrong-folder problem. You write a script, you run

python hello.py, and your terminal responds like it has never met you before: “No such file.” That’s not

Python being mean; it’s Python being literal. Your terminal can only run files that exist in the folder you’re currently

in. A helpful habit is to say out loud: “Where am I?” (About your folder. Not existentially. Save that for later.)

Another classic: indentation drama. Beginners often assume spacing is “just style.” In Python, indentation

is structure. A missing four spaces can change the meaning of your program. The moment you see IndentationError,

don’t panic. Look for code blocks after if, for, while, def, and

try. Make sure everything inside the block is indented the same way. If your editor has “show whitespace,”

turn it on oncejust onceand you’ll understand why developers sometimes talk about spaces like they’re precious gems.

Then there’s the input surprise: you expect numbers, but input() always gives you text.

That’s why "2" + "2" becomes "22" instead of 4. It’s not broken; it’s doing string

concatenation. Once you learn to convert with int() or float() (and wrap it in try/except

when needed), you start to feel like you’re in control again. This is also the moment many learners realize programming

is mostly about being precise with assumptions: “What type is this value? What shape is this data? What did I actually ask for?”

A surprisingly emotional experience is the first time you install a package and get ModuleNotFoundError anyway.

This often happens because the package got installed into one Python environment, but you’re running a different interpreter.

It’s like buying groceries and leaving them at a neighbor’s house, then wondering why your fridge is empty. The fix is

usually: activate your virtual environment and install again, or ensure your editor is using the same interpreter you run

in the terminal. Once you connect those dots, Python stops feeling random and starts feeling consistent.

Finally, there’s the “I rewrote it three times and now it works, but I’m not sure why” phase. That’s normal too.

The goal at the start isn’t perfectionit’s repeatability. Can you create a file, write a few lines, run it,

and understand what happened? If yes, you’re building the muscle that matters. Keep your programs small, name files clearly,

run them often, and treat errors like clues instead of insults. Eventually, those “mysterious” failures become familiar patterns,

and you’ll catch them before they even happen. (Which is the closest thing programming has to a superpower.)

Conclusion

Creating a very simple program in Python is less about memorizing syntax and more about building a repeatable workflow:

install Python, choose an editor, write a .py file, run it, and improve it in small steps. Start with a

print statement, add input, add logic, and wrap it in a main() function with a main guard. That’s a real foundation.

From there, you can build bigger ideasone small, working script at a time.