Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “High Quality Investment Research” Really Means

- Step 1: Start With the Right Question (and the Right Time Horizon)

- Step 2: Treat Data Like ProduceCheck for Bruises

- Step 3: Build a Repeatable Research Framework (So You Don’t Wing It Under Stress)

- Step 4: Combine Narrative and Numbers (Because Spreadsheets Don’t Run Businesses)

- Step 5: Analyze Business Quality and Competitive Advantage

- Step 6: Do Valuation Like an Adult (With Sensitivities and Humility)

- Step 7: Think in Probabilities, Not Certainties

- Step 8: Identify Conflicts of Interest (Yes, Even When the Chart Is Pretty)

- Step 9: Write It Down (Because Your Brain Is a Beautiful Liar)

- Step 10: Use a Checklist (So You Don’t Forget the Obvious in the Heat of Battle)

- A Worked Example (Hypothetical): Turning Research Into a Decision

- Conclusion: Research That Holds Up (Even When Markets Don’t)

- Field Notes: 5 “Real-Life” Experiences That Make Research Better (and More Human)

The modern investor’s problem isn’t a lack of information. It’s the opposite: a firehose of charts, hot takes, “must-buy” lists,

and backtests that look like they were engineered by a mad scientist with a spreadsheet addiction.

The internet gives you instant access to almost every fact… which is dangerously close to having none of them, because you still

have to decide what matters, what’s noise, and what’s secretly sponsored by someone who really wants you to click “Buy.”

High quality investment research isn’t the loudest research. It’s the kind that survives daylight: it explains the data, admits what it

can’t know, shows the other side, and helps you make a decision that still looks reasonable after you’ve slept on it.

This guide synthesizes best practices used by professional research shops, regulators, and valuation expertsthen translates them into

a practical, repeatable process you can actually use without needing a Bloomberg terminal (or a spare soul to sell).

What “High Quality Investment Research” Really Means

Let’s define the target before we start throwing darts. High quality investment research should do four things:

- Clarify reality: What is true about the business, the asset, and the environmentand what is merely assumed?

- Translate reality into value: What are the cash flows, risks, and scenarios that could justify today’s price?

- Expose uncertainty: What would have to happen for the thesis to be wrong (and how painful would that be)?

- Improve decisions: Not “predict markets,” but help you choose, size, and revisit positions intelligently.

A key theme from “A Wealth of Common Sense” is that good research respects the limits of data and the messiness of markets:

it understands the dataset, looks for robustness, adds context, considers the other side, and uses probabilistic thinking.

That mindset will keep you from building a portfolio out of correlations that only exist because someone tortured a dataset until it confessed.

Step 1: Start With the Right Question (and the Right Time Horizon)

Before you open a spreadsheet, decide what problem you’re solving. “Is this stock going up?” is not a research question.

Better questions look like:

- “What would need to be true for this company to compound cash flows for 5–10 years?”

- “Is the market pricing in unrealistically high growth (or unrealistically bad news)?”

- “What are the 3–5 variables that actually drive intrinsic value here?”

- “What’s my edgeinformation, time horizon, temperament, or a repeatable process?”

Your time horizon changes everything. A one-month trade lives and dies on catalysts, sentiment, and positioning.

A five-year investment lives and dies on business quality, unit economics, capital allocation, and the durability of competitive advantages.

Mixing those horizons is how investors end up panic-selling a long-term idea because of short-term headlines.

Step 2: Treat Data Like ProduceCheck for Bruises

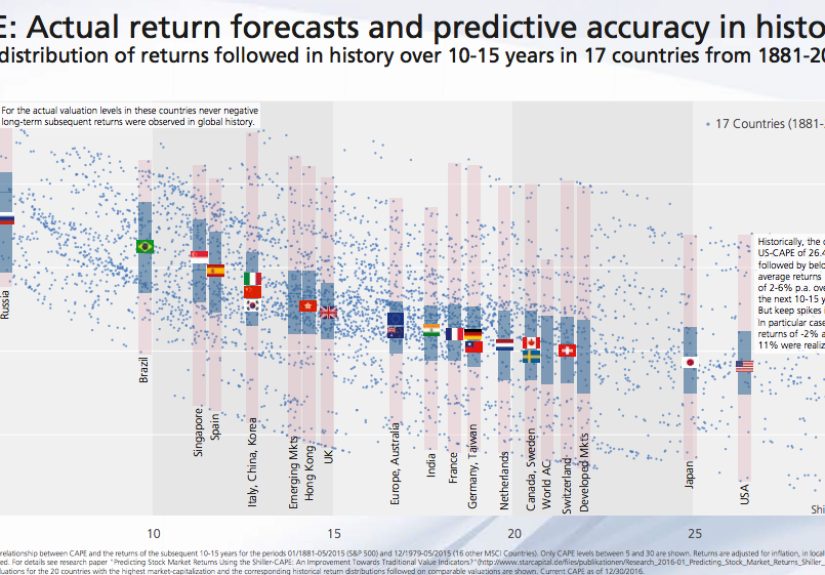

Data is not automatically truth. Market and fundamental datasets contain errors, missing periods, survivorship bias, changing definitions,

and structural shifts (like sector composition changes over time). If your research depends on historical relationships, you need to know

exactly what the numbers represent.

Three data rules that save portfolios

- Understand the source: Who created the dataset? What’s included, excluded, restated, or estimated?

-

Demand robustness: If a result only works in one time period, one market, or one cherry-picked filter,

it’s not a “finding.” It’s a “fun fact that will betray you later.” -

Add context: Numbers without context are how smart people get confidently wrong. Ask:

“What changed?” “What’s different now?” “Where could this break?”

If you do quantitative research, you also need defenses against data mining and backtest overfitting.

AQR has argued that out-of-sample testing and insisting on a real economic rationale are among the most important tools for separating signal from noise.

Research Affiliates has similarly emphasized that backtests without intuition and theory can quickly turn into “data-mining theater.”

Translation: if you can’t explain why something should work going forward, the backtest is just a historical costume party.

Step 3: Build a Repeatable Research Framework (So You Don’t Wing It Under Stress)

Professionals don’t rely on vibes. They rely on structure. One widely used research blueprint (especially in equity research and analyst training)

includes:

Core sections of a strong research write-up

- Company/business overview: What it sells, to whom, and why customers choose it.

- Investment thesis: The 2–4 reasons this is mispriced, plus what would prove you wrong.

- Catalysts: What could close the gap between price and value (or reveal the truth).

- Valuation: DCF and/or relative valuation, with clear assumptions and sensitivities.

- Key risks: Operational, financial, competitive, regulatory, and “thesis-killers.”

- Decision & sizing: Buy/hold/sell (or watchlist), and how bignot just whether.

This structure shows up repeatedly across analyst training materials and real-world research report formats for a reason:

it forces you to turn knowledge into a decision, not a Wikipedia page with feelings.

Step 4: Combine Narrative and Numbers (Because Spreadsheets Don’t Run Businesses)

NYU professor Aswath Damodaran is famous for pushing a simple point: valuation is built from both

a story (the business narrative) and the numbers (the model).

If your story is vague, your model is fake precision. If your model is detailed but your story is nonsense,

you’ve built an expensive lie with perfect formatting.

How to connect story → drivers → model

- Story: “This company will expand because it lowers customer pain and switching is hard.”

- Drivers: Retention, pricing power, customer acquisition efficiency, gross margin, reinvestment needs.

- Model inputs: Revenue growth, operating margin, sales-to-capital, discount rate, terminal assumptions.

- Reality checks: Compare to base rates (industry norms), competitor economics, and plausible constraints.

The best models are readable, not magical. If you can’t explain the top three drivers of value in one minute,

the model is probably doing interpretive dance.

Step 5: Analyze Business Quality and Competitive Advantage

High quality research spends more time on the business than the ticker. Two common approaches:

Moat/advantage analysis

Morningstar’s methodology centers on identifying durable competitive advantages (often summarized as an “economic moat”)

and evaluating whether those advantages are strengthening, stable, or deteriorating over time.

Morgan Stanley’s work on assessing strategy similarly emphasizes that understanding the business model and competitive position

is central for long-term investors.

Practical moat questions:

- Why do customers stay? Switching costs, habit, contracts, ecosystem lock-in?

- Why can’t competitors copy it? Scale, cost advantage, distribution, IP, network effects?

- Where does pricing power come from? Brand, differentiation, necessity, compliance?

- What’s the “moat trend”? Improving, stable, or erodingand what evidence supports that view?

Step 6: Do Valuation Like an Adult (With Sensitivities and Humility)

Valuation isn’t about one precise number. It’s about a range.

Your job is to map reality into possible outcomes and decide whether the current price offers enough upside for the risk you’re taking.

A simple valuation stack

- Base case: Reasonable assumptions that would not get you laughed out of a room full of analysts.

- Downside case: What breaks? Lower growth, margin pressure, higher reinvestment, higher discount rate.

- Upside case: What must go right? Not “hope,” but specific drivers: retention, pricing, scale efficiencies.

- Sensitivities: How much does value change if growth is ±2%, margins ±3%, discount rate ±1%?

If your investment only works in the upside case, it’s not a thesisit’s a prayer with a ticker symbol.

Step 7: Think in Probabilities, Not Certainties

“A Wealth of Common Sense” highlights probabilistic thinking as a hallmark of useful market research:

weigh the benefit of being right against the cost of being wrong. That’s how professionals survive uncertainty.

A quick probability template

- Outcome A (40%): Base case plays out, valuation gap closes over 2–3 years.

- Outcome B (35%): Business is fine but re-rating takes longer; returns are mediocre.

- Outcome C (25%): Thesis breaks; downside is meaningful.

Then ask: if Outcome C happens, do you lose 15% or 60%? Probabilities without payoff math are just vibes in a lab coat.

Step 8: Identify Conflicts of Interest (Yes, Even When the Chart Is Pretty)

Regulators spend a lot of time on conflicts because conflicts quietly poison research.

The SEC has explicitly stated that broker-dealers, advisers, and financial professionals generally have at least some conflicts of interest,

and emphasizes identifying and addressing them through policies, procedures, and mitigation.

FINRA rules governing research analysts and reports also focus on clear, prominent disclosures and conflict management.

What this means for you (even as a DIY investor)

- Ask who benefits if you believe the thesis.

- Look for disclosures about compensation, banking relationships, ownership, or incentives.

- Be skeptical of “research” that reads like marketing copy with a price target taped to it.

You don’t have to become a cynic. Just become a grown-up. Big difference.

Step 9: Write It Down (Because Your Brain Is a Beautiful Liar)

Writing your investment thesis forces clarity and makes future review possible.

A thesis should include:

- The reason it’s mispriced (not just “it’s good”).

- The key drivers that would make it work.

- The disconfirming evidence you’d watch for.

- Your time horizon and what success looks like.

- Your exit rules (valuation reached, thesis breaks, opportunity cost, better idea).

This also protects you from “research amnesia,” where you forget why you bought something and invent a new reason that conveniently

matches today’s emotions.

Step 10: Use a Checklist (So You Don’t Forget the Obvious in the Heat of Battle)

Many professional investors use checklists to prevent unforced errors. A checklist doesn’t give you new information;

it helps you consistently use the information you already haveespecially under pressure.

Think of it as guardrails, not handcuffs.

Example mini-checklist (steal this, improve it, pretend you invented it)

- Have I identified the 3 drivers of value?

- What would make the thesis wrong in 6–12 months?

- Did I consider at least one strong bear case?

- What assumptions does my valuation depend on most?

- Is there a conflict of interest or incentive distortion?

- What’s the downside if I’m wrong?

A Worked Example (Hypothetical): Turning Research Into a Decision

Imagine you’re researching “Acme Payments,” a fictional payments platform.

Your research process might look like this:

1) Business + moat

Customers integrate Acme into checkout flows (switching costs). Acme improves conversion rates (value creation).

Competitive risk: larger platforms bundling payments with other services.

Evidence: retention trends, take-rate stability, merchant cohort performance.

2) Thesis

- Market underestimates long-term margin expansion from scale and automation.

- Recurring revenue grows as merchants add services (fraud tools, billing, embedded finance).

- Risks: pricing compression, regulatory costs, platform disintermediation.

3) Valuation

You model three scenarios with different growth and margin paths. You run sensitivities on discount rate and terminal margin.

You don’t declare a single “fair value.” You identify a fair value range.

4) Decision

If today’s price is below the downside-weighted value and the thesis has identifiable milestones, it’s a candidate.

If it only works in the heroic case, it goes on the watchlist with a note:

“Good business, not a good priceyet.”

Conclusion: Research That Holds Up (Even When Markets Don’t)

High quality investment research is less about being clever and more about being honest:

honest about data limitations, honest about incentives, honest about uncertainty, and honest about what would prove you wrong.

The goal is not to predict the future perfectly; it’s to make decisions you can defend, improve, and repeat.

If you take nothing else from this: demand robustness, add context, consider the other side, and think in probabilities.

Then write it down, use a checklist, and revisit your work with the humility of someone who has met the market before.

Field Notes: 5 “Real-Life” Experiences That Make Research Better (and More Human)

The following are common experiences many investors run into while building a serious research processshared here as practical lessons

rather than personal claims. If they feel familiar, congratulations: you are learning the hard way, like the rest of civilization.

1) The “Spreadsheet Confidence” Trap

There’s a momentusually around the time you color-code your assumptionswhen your model starts to feel like truth.

That’s when you’re most dangerous. The model becomes a confidence machine: every cell looks precise, every chart looks definitive,

and suddenly you’re arguing that revenue growth will be exactly 17.3% because… the spreadsheet said so.

The practical fix is to force the model to confess what it’s sensitive to. If a tiny change in margin assumptions

turns your “strong buy” into “call a therapist,” then your conviction should live in the business drivers, not the decimals.

In practice, investors get better when they stop worshiping precision and start respecting ranges.

2) The Day You Discover Your “Good Data” Isn’t That Good

Another rite of passage: you build a beautiful backtest, then realize the dataset had survivorship bias,

or the accounting definition changed, or half the early years were stitched together with estimates and hope.

This is where many people either quit (understandable) or learn the most valuable skill in research:

interrogating your inputs. The strongest researchers don’t just ask, “What does the chart say?”

They ask, “What would make this chart misleading?” Over time, this habit becomes instinct. You start checking

methodology notes, looking for regime changes, and treating “too good to be true” as a smoke alarm, not a trophy.

3) The Awkward Joy of Writing the Bear Case First

Writing the bear case before the bull case feels like eating vegetables before dessert.

But it does something magic: it breaks the spell of confirmation bias.

In real workflows, some investors force themselves to write a one-page “Why this is a bad idea” memo first.

It’s uncomfortable, because you’re arguing against your own excitement, but that’s the point.

You begin to notice which risks are real (unit economics, competition, regulation) and which are just “scary headlines.”

Better yet, you discover which risks are uncapped (the kind that can permanently impair capital).

Over time, writing the bear case doesn’t make you pessimisticit makes you appropriately priced.

4) The First Time You Change Your Mind for the Right Reason

Most people think good investing is “having conviction.” Real growth is learning when to update.

A common experience: you buy (or nearly buy) a company because of a clean thesisthen new evidence appears.

Maybe retention weakens. Maybe a competitor changes the pricing structure. Maybe margins don’t scale the way you expected.

The immature reaction is to defend the thesis because your ego is attached to being “right.”

The mature reaction is to treat research like a living document: “Here’s what I believed, here’s what changed,

here’s what that does to value, and here’s my updated probability.”

The moment you genuinely change your mind because reality changed (not because you got scared),

your research process levels up.

5) The Calm Power of a Boring Routine

The most underrated “experience advantage” in investment research is consistency.

Investors often imagine that professionals win by discovering secret information.

More often, they win by doing the obvious work repeatedly: reading filings, tracking drivers,

writing theses, updating scenarios, and reviewing decisions.

It’s boringright up until the market panics. That’s when your routine becomes a superpower.

While others react to noise, you can say, “What changed in the drivers? What changed in the odds?

Is this fear justifiedor is it a discount?”

In real life, the routine is what gives you the courage to act rationally when the crowd is sprinting in circles.

The goal isn’t to become emotionless. It’s to build a process that keeps emotions from driving the car.