Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why 1930s Mugshots Hit Different

- The 9 Colorized Mugshots And The Real Stories Behind Them

- 1) John Dillinger The Escape Artist Who Turned Into a National Obsession

- 2) Bonnie Parker The Poet Who Became a Symbol (Whether She Wanted That Job or Not)

- 3) Clyde Barrow The Man Who Couldn’t Outrun His Own Choices

- 4) George “Machine Gun” Kelly The Kidnapping Case That Helped Popularize “G-Men”

- 5) Lester “Baby Face” Nelson A Youthful Look Paired With a Violent Reputation

- 6) Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd The Robin Hood Myth That Won’t Quit

- 7) Alvin “Creepy” Karpis The Planner Who Stayed on the FBI’s Radar

- 8) Kate “Ma” Barker The Mythical Mastermind vs. the Historical Record

- 9) Charles “Lucky” Luciano The Crime Boss Brought Down by the System He Manipulated

- What These Mugshots Say About America in the 1930s

- How I Approach Colorizing Mugshots Responsibly

- Behind The Pixels: My Colorizing “Field Notes” (An Extra 500+ Words Of Experience)

- Conclusion

Black-and-white mugshots have a weird superpower: they make history feel both far away and way too close.

The lighting is harsh, the background is blank, and the expression says, “Yes, officer, I would like to speak to my publicist.”

Colorizing these photos doesn’t “upgrade” the past so much as it removes the comfy distance. Suddenly, the 1930s aren’t sepia-tinted folklore

they’re people with skin tones, tired eyes, cheap suit fabric, and consequences.

One important note before we dive in: these stories aren’t here to glamorize crime. Real victims, real fear, real damage.

If anything, color can make that clearerbecause it stops the brain from treating the past like a movie still.

With that said, let’s step into the Public Enemy era and meet nine infamous names through the most unflattering photo genre ever invented:

the booking picture.

Why 1930s Mugshots Hit Different

The Great Depression made “outlaws” feel like headlines with legs

The 1930s were an economic gut-punch. Banks failed, jobs vanished, and trust in institutions went on an extended vacation without leaving a forwarding

address. In that climate, certain criminals became household namespartly because newspapers needed drama, and partly because “someone sticking it to

the system” was an easy story to sell. It wasn’t accurate, but it was catchy. And catchy is always dangerous.

Federal law enforcement was leveling up in real time

The decade also featured a major shift in policing. Criminals crossed state lines in fast cars; law enforcement had to adapt.

The Bureau of Investigation (which soon became the FBI) leaned into fingerprinting, coordinated investigations, and publicity campaigns.

Mugshots weren’t just records anymorethey were marketing for manhunts.

What colorization can (and can’t) do

Colorization can’t magically reveal an exact eye color or the true shade of a tie. What it can do is restore texture:

the clammy light of a jail hallway, the faded wool of a budget suit, the human reality behind the legend.

When I colorize, I treat it like historical illustrationgrounded in research, transparent about what’s interpreted, and always allergic to hero worship.

The 9 Colorized Mugshots And The Real Stories Behind Them

1) John Dillinger The Escape Artist Who Turned Into a National Obsession

John Dillinger’s name still lands with a thud. During the early 1930s, he became the poster figure for Midwest bank robberies and dramatic escapes.

In January 1934, he was captured in Tucson, Arizona, after locals recognized him. A few weeks later, he was held at Crown Point, Indianawhere

authorities famously bragged the jail was “escape-proof.” That confidence aged poorly.

On March 3, 1934, Dillinger escaped Crown Point by threatening guards with what he later claimed was a wooden gun, then driving off in a stolen car

which also created federal jurisdiction because he crossed state lines in a stolen vehicle. By July 1934, his run ended outside Chicago’s Biograph Theater.

The legend hardened into pop culture, but the real story is a reminder: charisma doesn’t cancel harm.

Color notes: I resisted the urge to make him look “cinematic.” I kept the palette plainmuted skin tones under harsh indoor light, a

tired, everyday shirt color, and the kind of dull backdrop that screams “county facility.” The effect is intentionally unromantic: not an outlaw icon,

just a man caught by the camera.

2) Bonnie Parker The Poet Who Became a Symbol (Whether She Wanted That Job or Not)

Bonnie Parker is often treated like a rebellious brand. In reality, she was a young woman swept into a violent, fast-moving criminal orbit during the

Depression years. Along with Clyde Barrow and their associates, she became part of a spree that included robberies, kidnappings, and deadly encounters

with law enforcement between 1932 and 1934.

The FBI’s historical case summary emphasizes the scale of the manhunt and the danger authorities believed the duo posed, culminating in their deaths

during a police ambush in Louisiana on May 23, 1934. Over time, movies and myths softened edges and sharpened aesthetics. But aesthetics are cheap.

The real costs were paid by people who didn’t get their names in the headlines.

Color notes: For Bonnie’s mugshot, I aimed for “human, not poster.” Natural lip tones, subdued shadows, and a conservative approach to

clothing color based on common fabrics of the erano dramatic reds, no rebellious glam. The goal is to pull the image back from legend and into reality.

3) Clyde Barrow The Man Who Couldn’t Outrun His Own Choices

Clyde Barrow had been involved in crime before he met Bonnie in 1930, and prison time only deepened his criminal trajectory.

Once the duo began moving with accomplices, their story became as much about mobility as it was about robberycars, roads, motels, and constant flight.

That movement helped them evade local police for stretches, but it also escalated the attention and coordination aimed at stopping them.

The public sometimes imagined them as folk heroes striking at banks. Even reputable historical discussions note the “Robin Hood” aura that clung to

Depression-era criminals in popular imagination. But myth doesn’t equal motive, and motive doesn’t erase consequences.

Color notes: Clyde’s mugshot colorization is all about restraint: slightly sallow indoor lighting, understated shirt tones, and realistic

shadowing around the eyes. It’s a visual reminder that the “outlaw couple” story wasn’t a romanceit was a collision.

4) George “Machine Gun” Kelly The Kidnapping Case That Helped Popularize “G-Men”

George “Machine Gun” Kelly (born George Barnes) is best known for the 1933 kidnapping of oilman Charles F. Urschel. The case became a landmark

because it showcased multi-state investigative coordination. After his arrest in September 1933, Kelly and his wife Kathryn were tried and sentenced

to life in prison on October 12, 1933.

There’s also the famous line“Don’t shoot, G-Men!”often attributed to Kelly at his surrender. The FBI itself notes the quote is doubtful, but the

phrase stuck and helped cement the popular image of federal agents. It’s one of those moments where legend rides on the back of a maybe.

Color notes: Kelly’s mugshot is a masterclass in “bad lighting meets worse decisions.” I kept skin tones slightly washed (as they often

appear under harsh bulbs) and avoided overly crisp suit colors. If it starts looking like a movie still, I dial it back.

5) Lester “Baby Face” Nelson A Youthful Look Paired With a Violent Reputation

Lester Gillis, known as “Baby Face” Nelson, is remembered for a youthful appearance and an exceptionally violent criminal record.

He robbed banks, clashed repeatedly with law enforcement, and became associated with the Dillinger orbit in the early 1930s.

The FBI’s famous-cases profile describes him as a prolific and particularly violent criminal, and his story ends in 1934 after a confrontation with agents.

Nelson’s notoriety is a grim reminder that nicknames can be deceptive. “Baby Face” sounds like a jazz club act. The reality was far darker, and law

enforcement treated him as a severe threat.

Color notes: This one is all about contradiction: a younger-looking face in the stark setting of a booking photo.

I kept the colors muted and the mood coldbecause a “cool” palette is honest here. This is not a character. It’s a record.

6) Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd The Robin Hood Myth That Won’t Quit

Charles Arthur Floyd became famous under the nickname “Pretty Boy,” a label he reportedly disliked. He was a bank robber whose exploits became

national news. Some accountsespecially in popular culturecast him as a Depression-era “Robin Hood,” even claiming he destroyed mortgage documents.

Regardless of how that legend grew, Floyd’s real criminal career included armed robberies and serious violence.

He was also linked in the public mind to the 1933 Kansas City Massacre case, an event that shocked the nation and fueled new federal crime laws.

Historians still debate aspects of involvement and attribution, but the incident undeniably accelerated public demand for stronger federal enforcement.

Floyd was killed in October 1934 in Ohio after a long manhunt.

Color notes: I avoided the “handsome outlaw” trap: no warm hero lighting, no flattering contrast.

Instead, I leaned into the drab reality of the eradusty neutrals, worn fabric tones, and the kind of flat background that refuses to mythologize anyone.

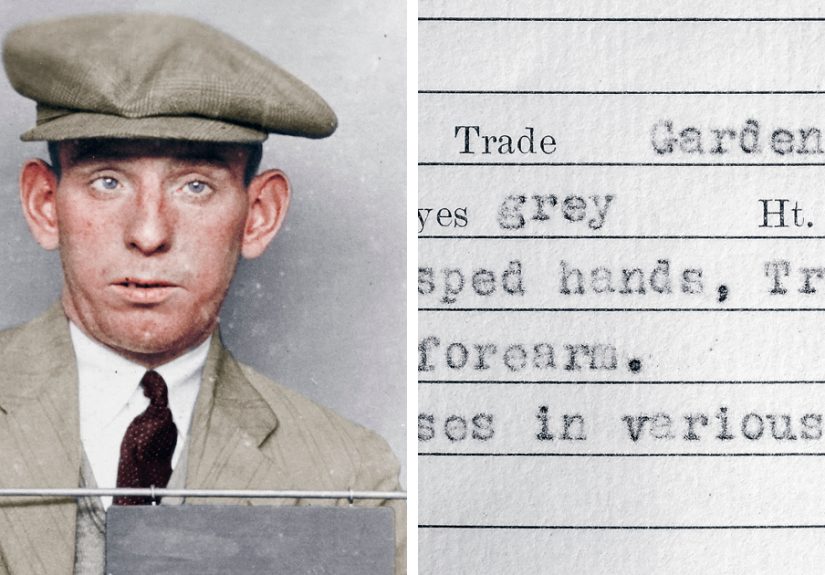

7) Alvin “Creepy” Karpis The Planner Who Stayed on the FBI’s Radar

Alvin Karpis was a central figure in the Barker-Karpis gang, connected to bank robberies and two major kidnappings in the 1930s.

The FBI’s case history notes his capture in New Orleans on May 1, 1936, involving FBI agentsand famously, Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Karpis was sent to Alcatraz and served a long sentence, becoming a symbol of the era’s organized, mobile crime.

Compared to headline-grabbing bank robbers, Karpis represents something more methodical: planning, networks, and logistics.

If the 1930s “public enemy” era had a corporate office (it didn’t, thankfully), Karpis would’ve been running the calendar invites.

Color notes: Karpis’s mugshot is one of the most striking because it feels almost “composed.”

I kept the color subtleslight warmth in skin tones, realistic hair shading, and conservative clothing colorsso the image stays documentary, not dramatic.

8) Kate “Ma” Barker The Mythical Mastermind vs. the Historical Record

“Ma Barker” is one of the most misunderstood figures of the era. For decades, media painted her as the criminal genius behind her sons.

Modern historical treatmentsespecially in FBI materialspush back on that framing, suggesting the “mastermind” image was exaggerated.

What isn’t disputed is her proximity to the Barker gang’s activities and her presence in the gang’s orbit.

In January 1935, federal agents located a Florida hideout connected to the Barkers. The confrontation ended with Ma and her son Fred dead.

The episode became part of the FBI’s broader “war on crime” narrativeone more chapter in a decade where the line between policing and publicity

was getting thinner.

Color notes: I treated Ma’s image with the most caution. Colorization can accidentally “cast” someone into a rolevillain, boss,

mastermindjust by adding warmth or polish. I kept the palette plain and slightly weary, emphasizing age, stress, and realism over legend.

9) Charles “Lucky” Luciano The Crime Boss Brought Down by the System He Manipulated

Charles “Lucky” Luciano wasn’t a roaming bank robberhe was a major organized-crime figure tied to the reshaping of American criminal networks in the

early 1930s. In 1936, he was prosecuted by New York’s Thomas E. Dewey and convicted on charges connected to compulsory prostitution/pandering.

He received a lengthy sentence (commonly summarized as 30 to 50 years).

Luciano’s story highlights something the 1930s did increasingly well: turning complex criminal enterprises into cases that could be proved in court.

The mugshot from 1936 is especially striking because it looks less like a desperado and more like someone who expected to negotiate his way out.

Spoiler: the judge did not accept coupons.

Color notes: For Luciano, I leaned into the “boardroom criminal” vibe without flattering itneutral suit tones, realistic skin shading,

and a slightly cool background. Color makes it harder to treat him like a caricature. He looks like a man whose crimes wore a tie.

What These Mugshots Say About America in the 1930s

Put these nine images together and a pattern emerges: the 1930s weren’t just about “bad guys with guns.” They were about speed (cars), publicity

(newspapers), and the federalization of crime fighting (jurisdiction, fingerprints, coordinated investigations). Mugshots became part of a national

conversationsometimes as warnings, sometimes as morbid celebrity photos.

Colorization doesn’t change the facts, but it changes how we receive them. When you can see the warmth in skin, the dullness of cheap cloth,

the slight discoloration under a harsh light, it’s harder to treat history like entertainment. And that’s a good discomfort.

How I Approach Colorizing Mugshots Responsibly

1) Research first, aesthetics last

I start with what’s knowable: typical fabric colors of the era, lighting conditions in police stations, the way early film stocks render contrast.

If a detail can’t be confirmed (eye color, exact suit shade), I avoid claiming it as fact. “Plausible” is not the same as “proven.”

2) No glam, no hero lighting

The biggest risk in colorizing criminals is accidental myth-making. Add a warm glow, increase contrast, and suddenly it’s a movie poster.

I keep tones grounded and slightly restrained, because a mugshot is documentation, not branding.

3) Always remember the unseen people

The camera only captured the arrested. It didn’t capture the people robbed, threatened, injured, or traumatized.

When I write these stories, I try to keep the focus where it belongs: on historical truth and human cost, not outlaw fandom.

Behind The Pixels: My Colorizing “Field Notes” (An Extra 500+ Words Of Experience)

The first time I colorized a 1930s mugshot, I expected the “wow” moment to be the obvious one: skin tone, eyes, hairboom, history becomes real.

But the real gut-punch wasn’t the face. It was everything around it.

In black-and-white, you can pretend the background is abstract. In color, the background becomes a place. The wall looks like a wall you’ve leaned

against in a boring hallway. The light looks like the kind that makes everyone seem tired. You start noticing tiny, unglamorous truths:

the slight sheen of sweat under a hot bulb, the dullness of a shirt that’s been worn too many times, the way certain shadows suggest a room that

smells like paper, metal, and stale air.

I also learned quickly that “accuracy” is a slippery word. The internet loves a bold claim: “This is exactly what he looked like!”

But unless we have color references (documents, clothing preserved, reliable descriptions), we don’t get to say “exactly.”

So I treat colorization like a museum diorama: research-heavy, plausible, and honest about what’s interpretive.

If I can’t verify a detail, I choose restraint over drama.

The emotional part surprised me, too. It’s easyalmost automaticto absorb the pop-culture version of these people: Dillinger as the charming outlaw,

Bonnie and Clyde as doomed lovers, Luciano as the stylish crime boss. But when you sit with a mugshot for hours, you stop seeing the “character.”

You see someone who ate, slept, worried, and made choices that hurt others. That doesn’t create sympathy for the crimes. It creates clarity that the

crimes weren’t committed by movie villains. They were committed by real humans, which is exactly why they’re so frightening.

And yes, there’s a weird technical comedy to it. One minute you’re reading about federal jurisdiction and major historical events; the next minute

you’re zoomed in 400% trying to decide if a shadow on a collar is “dusty beige” or “sad oatmeal.” You become a detective of tiny things.

Fabric textures matter. The warmth of indoor light matters. Even the “wrong” kind of blue can make a face look like it belongs in 1978 instead of 1934.

The biggest lesson? Color doesn’t just add lifeit adds responsibility. If you brighten a criminal’s eyes and warm the tones too much, you can

accidentally make them look heroic. If you over-darken, you can turn them into a cartoon monster. The truth is usually neither.

So I aim for the most historically boring choice possible, because boring is often closer to reality than “cinematic.”

When I finish a set like this, I don’t feel like I’ve “revived legends.” I feel like I’ve deglamorized them.

The faces are more real, the setting is more ordinary, and the story becomes harder to treat as entertainment.

That’s the point. History isn’t here to be aesthetic. It’s here to be understood.

Conclusion

Colorizing 1930s mugshots is like turning down the background music on a myth. Suddenly you can hear the real story: the fear, the pursuit, the

institutional changes, and the human cost. These nine criminals didn’t live in a noir fantasythey lived in a country under stress, in an era when

publicity and law enforcement were evolving fast.

If these images do anything valuable, I hope it’s this: they make the past feel close enough to learn fromwithout turning it into a fan club.