Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick kidney-stone basics (so you’re not Googling at 2 a.m.)

- Types of kidney stones (because not all rocks are the same)

- What causes kidney stones in the first place?

- Diagnosis: how clinicians confirm a stone (and why size matters)

- What to expect when you pass a kidney stone

- How kidney stones are treated

- Prevention: how to reduce the chance of a repeat stone

- “I passed a stone… now what?” Follow-up that actually matters

- Kidney stones in kids and teens (yes, it happens)

- Bottom line

- Experiences From the Real World: What Passing a Kidney Stone Often Feels Like (and What People Wish They’d Known)

- 1) “The pain isn’t steadyit’s a roller coaster.”

- 2) “Hydration is harder than it sounds when you feel nauseated.”

- 3) “The anxiety is realespecially the first time.”

- 4) “Straining urine feels weird, but it’s oddly satisfying.”

- 5) “Food changes are easier when you focus on swaps, not ‘never again.’”

- 6) “The biggest lesson: prevent the sequel.”

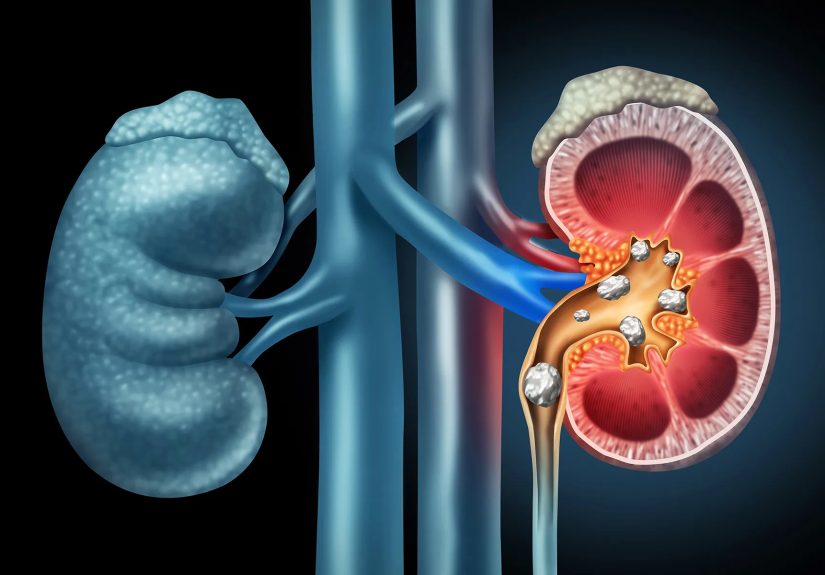

Kidney stones are the body’s least fun “arts-and-crafts” project: minerals and salts in urine decide to form crystals, the crystals clump, and suddenly you’ve got a tiny rock trying to exit through plumbing that was not designed for geology.

The good news? Many stones pass without surgery. The better news? Once you understand what type of stone you’re dealing with and what to expect during passage, you can make smarter choices to ease symptoms, avoid complications, and reduce the odds of a repeat performance.

Quick kidney-stone basics (so you’re not Googling at 2 a.m.)

A kidney stone (also called nephrolithiasis) is a hard deposit that forms when urine becomes concentrated and certain substances crystallize. Stones may stay in the kidney or move into the ureter (the tube connecting kidney to bladder).

Symptoms often start when a stone moves, irritates tissue, or blocks urine flowthink “traffic jam,” but with sharp edges and a dramatic soundtrack.

Common symptoms

- Sudden pain in the back, side, or lower abdomen that can come in waves

- Pain or burning when you urinate

- Urine that looks pink/red or cloudy

- Nausea or vomiting

- Frequent urge to urinate or urinating in small amounts

When symptoms are a “don’t-wait” situation

Some stone situations need urgent medical attention. Seek care right away if you have fever/chills, signs of infection, severe uncontrolled pain, persistent vomiting, trouble urinating, or you have only one kidney (or you’re pregnant).

A blocked urinary tract plus infection is an emergencynot a “let’s see how I feel after a nap” situation.

Types of kidney stones (because not all rocks are the same)

Knowing the stone type matters because prevention is not one-size-fits-all. The same diet tweak that helps one stone type can be useless (or even unhelpful) for another.

Here are the main categories clinicians talk about:

1) Calcium stones (calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate)

These are the most common. Calcium oxalate stones are the usual headliner, with calcium phosphate also showing upespecially when urine chemistry shifts (like higher urine pH).

Contrary to a popular myth, most people are not making stones because they “ate too much calcium.” In fact, getting enough dietary calcium can help by binding oxalate in the gut so less oxalate reaches the urine.

Common contributors: dehydration, high sodium intake, high oxalate intake (in susceptible people), certain metabolic conditions, and some digestive disorders that increase oxalate absorption.

2) Uric acid stones

Uric acid stones are more likely when urine is persistently acidic. Diets high in purines (found in many animal proteins, especially certain meats and seafood) can raise uric acid levels for some people.

The encouraging part: uric acid stones can often be preventedand sometimes treatedby shifting urine pH and addressing underlying risks.

3) Struvite stones (infection stones)

Struvite stones are commonly linked to urinary tract infections with certain bacteria. They can grow quickly and become large. If you’ve had recurrent UTIs, especially with fever or persistent symptoms, this type enters the conversation.

These stones often require medical management beyond “drink more water and hope for the best.”

4) Cystine stones

Cystine stones are less common and related to a genetic condition that causes cystine to leak into the urine.

They can recur and may require specialized prevention strategies with a clinician (often involving high fluid intake and urine chemistry management).

What causes kidney stones in the first place?

Most stones form when urine doesn’t have enough liquid to keep minerals dissolved. Think of sweet tea: with enough water, sugar dissolves; with too little water, crystals form at the bottom.

Now swap “sugar” for minerals and “bottom of the glass” for “kidney,” andunfortunatelyyou’ve got the idea.

Risk factors that show up a lot

- Not drinking enough fluids (especially in hot climates, heavy exercise, or jobs with limited bathroom breaks)

- High sodium intake (sodium can increase calcium in urine)

- High animal-protein intake (can affect urine chemistry and uric acid)

- History of stones (stones love sequels)

- Family history

- Digestive conditions that change absorption (in some people)

- Certain medications or supplements (your clinician can review these)

Diagnosis: how clinicians confirm a stone (and why size matters)

If symptoms suggest a kidney stone, clinicians usually combine history and exam with urine tests, blood tests, and imaging.

Imaging isn’t just about “yes or no.” It answers: Where is it? How big is it? Is it causing blockage?

Those details drive your optionswatchful waiting vs. medication vs. a procedure.

Common tests

- Urinalysis to look for blood, infection, and crystals

- Blood tests to assess kidney function and chemistry that raises stone risk

- Imaging (CT, ultrasound, or sometimes X-ray depending on the situation)

Many medical groups consider non-contrast CT a highly accurate test for confirming stones, but ultrasound may be preferred in certain situations to reduce radiation exposure (especially for some children and pregnant patients).

Your clinician balances accuracy, safety, and what they need to know right now.

What to expect when you pass a kidney stone

Passing a stone is usually less like “a smooth river pebble floating downstream” and more like “a tiny, determined burrito of discomfort traveling through a narrow hallway.”

But expectations help. Here’s the typical arc:

1) The “something is very wrong” phase

Pain often starts when the stone moves into the ureter. This pain can be intense and may come in waves (renal colic). Many people also feel nauseated because your body is multi-tasking: it’s trying to manage pain while still functioning like a normal organism.

2) The “is it moving?” phase

As the stone travels, pain location can shiftfrom the flank/side toward the lower abdomen or groin. Urinary urgency can show up when the stone gets closer to the bladder.

It’s common for symptoms to fluctuate rather than steadily improve.

3) The “final stretch” phase

When the stone reaches the bladder, many people feel significant relief. Passing it through the urethra (during urination) is often quickthough still uncomfortable for some.

If you’re asked to strain your urine, it’s to catch the stone for analysis. Stone analysis is one of the best “clues” for prevention.

How long does passage take?

The honest answer: it depends. The biggest predictors are size and location. Smaller stones are more likely to pass on their own; larger stones are less likely to pass without help.

A commonly cited pattern in medical literature is that stones ≤5 mm pass more often than stones 5–10 mm, and passage rates drop as size increases.

Location matters too: stones closer to the bladder may pass more easily than those higher up.

What “normal” can look like while passing

- Pain that comes and goes (sometimes sharply)

- Urinary urgency or frequency

- Mild blood in urine (can happen due to irritation)

- Feeling tired and worn out (because pain is exhausting)

What should not be ignored

- Fever, chills, or feeling acutely ill (possible infection)

- Inability to urinate

- Persistent vomiting or inability to keep fluids down

- Severe pain that isn’t controlled with recommended medications

How kidney stones are treated

Treatment ranges from “supportive care while it passes” to procedures that remove or break up stones.

The plan typically depends on stone size, location, symptoms, kidney function, and whether infection is present.

Conservative management (watchful waiting)

If the stone is small and there’s no infection or dangerous blockage, clinicians may recommend fluids, pain control, and follow-up.

You may be asked to strain your urine to capture the stone.

Medications

- Pain relief: often NSAIDs are used when appropriate; your clinician will guide what’s safe for you.

- Anti-nausea meds: if vomiting is an issue.

- Medical expulsive therapy: sometimes an alpha-blocker (like tamsulosin) is prescribed to relax the ureter and help certain stones passtypically based on stone size/location and patient factors.

Procedures (when a stone won’t pass or complications arise)

If a stone is too large, causing ongoing obstruction, or linked to infection or kidney problems, procedures may be recommended:

- Shock wave lithotripsy (SWL/ESWL): uses shock waves to break a stone into smaller pieces that can pass more easily.

- Ureteroscopy: a thin scope is passed through the urinary tract to reach and remove or laser-break the stone.

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL): typically for large or complex stones; involves removing the stone through a small incision.

Prevention: how to reduce the chance of a repeat stone

After you’ve had a kidney stone, prevention is not “optional homework.” It’s how you avoid re-living the plot.

The best prevention plan depends on stone type and your personal risk factors, but these strategies show up consistently:

1) Hydration: the number-one habit

The goal is to keep urine diluted. Many prevention plans aim for high urine volume (often around 2.5 liters of urine daily, which usually means drinking more than that).

Practically: aim for pale-yellow urine most of the time. If it’s dark yellow, your kidneys are basically texting you: “We need more water.”

2) Reduce sodium (yes, even if you don’t own a salt shaker)

Sodium hides in packaged foods, restaurant meals, sauces, and snacks. Higher sodium intake can increase calcium in the urine, raising risk for calcium-based stones in many people.

Reading labels and choosing lower-sodium versions can make a real difference.

3) Don’t fear dietary calcium (fear the lack of itsometimes)

For many calcium oxalate stone formers, adequate dietary calcium with meals can help by binding oxalate in the gut.

The key word is dietary. Supplements are a separate conversationyour clinician can advise based on your history and labs.

4) Be smart about oxalate (if you form calcium oxalate stones)

Oxalate is found in a range of healthy foods. The goal isn’t “never eat plants again.” It’s to identify high-oxalate culprits and balance themoften by pairing with calcium-containing foods and avoiding extreme intake.

If you’ve never had a calcium oxalate stone, don’t self-prescribe a low-oxalate diet just because the internet yelled at you.

5) Moderate animal protein and added sugar

High animal-protein diets can shift urine chemistry and raise stone risk in some people. Added sugars can also affect metabolic factors tied to stone formation.

You don’t have to swear off burgers forever; you just want your daily pattern to support kidney health.

6) Citrate can be helpful

Citrate in urine can help reduce stone formation for certain people. Clinicians sometimes recommend dietary changes (like citrus intake) or prescribe citrate therapy depending on urine testing results.

“I passed a stone… now what?” Follow-up that actually matters

After the immediate crisis is over, the smartest move is to learn what happenedso you can prevent recurrence.

Depending on your situation, clinicians may recommend:

- Stone analysis (if you caught it)

- Blood work for calcium, kidney function, and related markers

- 24-hour urine testing to measure volume and stone-forming substances

- Follow-up imaging to ensure the stone passed and no silent obstruction remains

Kidney stones in kids and teens (yes, it happens)

Kidney stones can occur in children and teens too. Risk factors may include dehydration (sports + not enough water is a classic combo), certain medical conditions, and diet patterns.

Because growing bodies are different, evaluation and prevention in younger people often emphasize hydration strategies, safe imaging choices, and careful nutrition planning with a clinician or dietitian.

Bottom line

Kidney stones are common, painful, andannoyinglyoften recurrent. But they’re also highly “actionable.”

Knowing your stone type, understanding what passage can feel like, and working a prevention plan (hydration, diet adjustments, and targeted medical guidance) can dramatically reduce your chances of doing this again.

If you’re currently in the middle of symptoms, focus on safety first: uncontrolled pain, fever, or vomiting should push you toward prompt medical care.

Experiences From the Real World: What Passing a Kidney Stone Often Feels Like (and What People Wish They’d Known)

Below are common, experience-based themes people report when dealing with kidney stones. These are illustrative “what it’s often like” snapshotsnot a substitute for medical advice, and not descriptions of any one specific person.

Think of it as a friendly field guide from the land of Why is my body doing this?

1) “The pain isn’t steadyit’s a roller coaster.”

A lot of people expect pain to build and then gradually fade. Kidney stone pain frequently laughs at that plan. Many describe waves: 20 minutes of “I can’t get comfortable,” then a short break, then the next wave.

That pattern can be scary because the breaks make you wonder if it’s overonly for the pain to return like a sequel nobody asked for.

Knowing this ahead of time helps you prepare: take pain medication as directed, use heat (like a heating pad), and don’t assume relief means the stone is gone.

2) “Hydration is harder than it sounds when you feel nauseated.”

“Drink more water” is excellent adviceunless you’re nauseated and every sip feels like negotiating with your stomach.

People often say they did better with small, frequent sips rather than chugging. Some also found that cold water, ice chips, or oral rehydration solutions were easier to tolerate than plain warm water.

If vomiting is persistent, that’s a sign you may need medical helpnot just because dehydration increases stone risk, but because you can’t safely manage at home if you can’t keep fluids down.

3) “The anxiety is realespecially the first time.”

First-time stone symptoms can feel alarming: severe pain, urine changes, and the uncertainty of what’s happening. Many people describe the emotional side as “almost as bad as the physical part,” because you’re trying to decide whether this is urgent, whether you’re overreacting, and whether you can make it through the next hour.

Practical comfort steps people commonly mention include: having a plan for where to go if symptoms escalate, keeping a phone charger nearby (seriously), and telling someone you trust what’s going on so you’re not handling it alone.

4) “Straining urine feels weird, but it’s oddly satisfying.”

If your clinician asks you to strain urine, it’s to catch the stone for analysis. Many people say it feels awkward at firstlike a science experiment they didn’t sign up for.

But catching the stone can be surprisingly empowering because it turns a mystery into data. Once the stone type is known, prevention advice becomes more precise.

People also mention that getting a clear plan after analysislike specific hydration goals or diet adjustmentshelps them feel less helpless about recurrence.

5) “Food changes are easier when you focus on swaps, not ‘never again.’”

After a stone, it’s tempting to go extreme: cut out every food someone on the internet blamed. In real life, sustainable prevention tends to be about patterns and swaps.

Common wins people report include:

- Switching from salty packaged snacks to lower-sodium options

- Building a “water routine” (a bottle they like, reminders, and refills tied to daily events)

- Eating balanced meals with adequate dietary calcium when appropriate

- Choosing more plant-forward meals while keeping animal protein moderate

One surprisingly helpful mindset: don’t treat prevention like punishment. Treat it like upgrading your kidney’s working conditions.

6) “The biggest lesson: prevent the sequel.”

People who’ve had multiple stones often say the second stone wasn’t just physically painfulit was emotionally frustrating, because it felt preventable.

The most consistent “wish I’d done this earlier” list looks like:

(1) drink more fluids daily, not just during symptoms;

(2) reduce sodium;

(3) follow up for stone analysis or urine testing if recommended;

(4) ask for a specific prevention plan instead of generic advice.

Kidney stones have a reputation for repeat appearances, but prevention stepsdone consistentlycan meaningfully reduce recurrence for many people.