Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Table of Contents

- How many layers of skin are there?

- Layers of skin in order (outer to inner)

- Diagram/model: a simple cross-section you can remember

- Epidermis: the barrier layer (and its strata)

- Dermis: the support-and-sensation layer

- Hypodermis: the padding and anchor (subcutaneous tissue)

- Thick vs. thin skin (why palms are “extra”)

- Why the layers matter (burns, acne, aging, biopsies)

- Memory tricks without the cringe

- Real-world experiences: what the layers feel like in daily life

- Sunburn: an epidermis lesson you didn’t ask for

- Blisters: when friction recruits deeper help

- Paper cuts and shallow scrapes: surface drama, quick recovery

- Deep cuts: welcome to the dermis (bring snacks… and maybe stitches)

- Tattoos: ink lives in the dermis for a reason

- Dry winter skin: barrier function in the spotlight

- Shots and injections: the hypodermis is a common destination

- “Why does my face feel different from my feet?”

- Wrap-up

Your skin is basically a high-performance jacket you never take off. It blocks germs, keeps your insides from

leaking out, helps you feel a mosquito before it steals a snack, and even plays a role in temperature control.

But if you’ve ever Googled “how many layers of skin are there?” you probably noticed something annoying:

different sources count them differently.

Let’s fix thatclearly, in order, with a diagram-style model you can picture in your head (or show your study group

like you totally didn’t panic-learn anatomy at 2 a.m.). We’ll cover the three main layers most

clinicians use (epidermis, dermis, hypodermis), plus the

five sublayers of the epidermis (the famous “stratum” squad).

How many layers of skin are there?

Most medical and clinical explanations describe three main layers:

epidermis (outer), dermis (middle), and hypodermis

(deepestoften called the subcutaneous tissue).

So why do you sometimes see “two layers”? Because some anatomy discussions call the epidermis + dermis the

“skin proper,” and treat the hypodermis as the layer under the skin. In real life, that distinction

matters less than understanding what each layer doesand where things happen (like where sweat glands live,

where tattoos sit, or why a deep cut bleeds like a crime scene in a soap opera).

Layers of skin in order (outer to inner)

From the outside world to your deeper tissues, the skin layers go like this:

-

Epidermis (outermost)

- Stratum corneum

- Stratum lucidum (only in thick skin: palms/soles)

- Stratum granulosum

- Stratum spinosum

- Stratum basale (deepest epidermal layer)

-

Dermis (middle)

- Papillary dermis (upper dermis)

- Reticular dermis (deeper, thicker dermis)

-

Hypodermis (deepest; subcutaneous tissue)

- Mostly fat + connective tissue; connects skin to muscle and bone

If you remember nothing else, remember this: epidermis is the “roof,” dermis is the “framework,” and

hypodermis is the “cushion + anchor.”

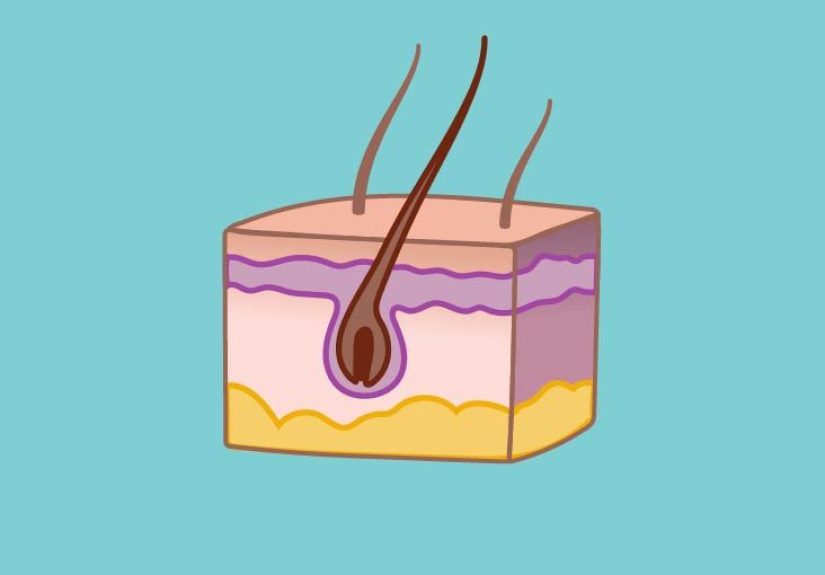

Diagram/model: a simple cross-section you can remember

Think of skin like a layered dessert… except it sweats and grows hair and occasionally breaks out before big events.

Here’s a clean, diagram-style model that shows the order of layers and where the “action items” live.

Dermis

• Hair follicles • Sweat glands • Sebaceous glands

• Blood vessels • Nerves • Collagen & elastin

Hypodermis (Subcutaneous Tissue)

• Fat + connective tissue • Insulation • Padding • Anchors skin to deeper structures

In a physical anatomy skin model, you’ll often see this cross-section with a hair follicle

dipping down into the dermis, a coiled sweat gland, and a fluffy-looking hypodermis at the bottom. The model

is basically screaming: “Most of the cool stuff is not in the epidermis.”

Epidermis: the barrier layer (and its strata)

The epidermis is the outer layer you can actually see. It’s relatively thin, and it works like

a smart barrier: tough enough to handle daily friction, but constantly renewing itself so you’re not walking around

with “vintage” skin cells from 2009.

What the epidermis does (in plain English)

- Protection: blocks many microbes and irritants.

- Water control: helps prevent excessive water loss.

- UV defense & pigment: melanocytes contribute to skin color and UV protection.

- Immune “early warning”: specialized cells help detect trouble.

The epidermis layers in order (top to bottom)

The epidermis is made of “strata” (layers) that reflect how keratinocytes mature as they move upward. From

superficial to deep:

1) Stratum corneum

This is the outermost “dead cell” layer that still does a ton of work. Cells here are flattened, packed with keratin,

and act like protective shingles on a roof. It’s also where gentle exfoliation products do their thingby helping

loosen the outermost cells (not by “scrubbing your face into a new personality”).

2) Stratum lucidum (only in thick skin)

This is a thin, clear-ish layer seen in thick skin like palms and soles. If you’re wondering why

your hands handle push-ups better than your eyelids: this is part of the answer.

3) Stratum granulosum

Cells here develop granules involved in keratin formation and help build the skin’s water barrier. This is a major

“waterproofing” zonelike your epidermis is sealing the deal before sending cells upward.

4) Stratum spinosum

Often called the “spiny” layer because of how the cells look under a microscope, this layer helps provide strength

and flexibility. It’s also where you’ll find important cellular connections that help the epidermis resist shear forces.

5) Stratum basale

This is the deepest epidermal layer, where new keratinocytes are generated. It’s also where melanocytes live,

contributing to pigment production. If the epidermis is a factory line, the basale is where the raw materials enter

the system.

Dermis: the support-and-sensation layer

The dermis is the thick, hardworking middle layer that gives skin its strength, stretch, and “bounce.”

It’s packed with connective tissue (hello, collagen and elastin), plus the infrastructure that keeps skin alive:

blood vessels, nerves, sweat glands, oil glands,

and hair follicles.

Papillary dermis vs. reticular dermis

The dermis is commonly described in two layers:

-

Papillary dermis: the more superficial portion, with looser connective tissue and lots of tiny vessels.

It interlocks with the epidermis, helping with nutrient delivery and anchoring. -

Reticular dermis: deeper and thicker, with denser collagen bundles that form the “bulk” of the dermis.

This is where a lot of your skin’s mechanical strength comes from.

What lives in the dermis (aka why it’s the busy neighborhood)

- Sensory nerves: touch, pain, temperatureyour dermis is basically a communication hub.

- Blood vessels: nourish tissues and help regulate heat (dilate to release heat, constrict to conserve).

- Glands: sweat glands for cooling; sebaceous glands for oil (sebum) that lubricates skin and hair.

- Hair follicles: the “root system” for hair growth.

Hypodermis: the padding and anchor (subcutaneous tissue)

The hypodermis (also called the subcutaneous layer) sits beneath the dermis and

connects your skin to deeper structures like muscle. It contains more fat (adipose) and looser connective tissue,

plus larger blood vessels and nerves.

What the hypodermis does

- Insulation: helps reduce heat loss.

- Energy storage: fat is an energy reserve.

- Shock absorption: cushioning for everyday bumps and pressure.

- Structural connection: helps “tack down” skin while still letting it move a bit.

This layer varies wildly depending on body area, age, and overall body composition. That’s why skin can feel thin and

delicate in some places (like eyelids) and plush in others.

Thick vs. thin skin (why palms are “extra”)

Most of your body has thin skin. Thick skin is found on the

palms and solesareas built for friction and pressure. Thick skin has:

- a more prominent stratum corneum (extra protection),

- the additional stratum lucidum,

- and (typically) no hair follicles on those “glabrous” surfaces.

In other words: your palms and soles are the “work boots” of your body, while most other regions are more like

“everyday sneakers.” Same brand, different job.

Why the layers matter (burns, acne, aging, biopsies)

1) Burns are described by depth

Burn severity isn’t just about how red something looksit’s about how deep the damage goes.

Superficial injuries mainly affect the epidermis. Deeper burns involve the dermis and can reach subcutaneous tissue,

changing pain levels, healing time, and scarring risk.

2) Acne is a “pilosebaceous unit” story

Acne doesn’t start on the surface “because your face is mad at you.” It involves oil glands and hair folliclesstructures

rooted in the dermis. That’s why many acne treatments target oil production, follicle turnover,

inflammation, and bacteria rather than just “scrubbing harder.”

3) Aging hits the dermis like gravity’s to-do list

Fine lines, laxity, and many texture changes are closely linked to dermal shiftsespecially changes in collagen, elastin,

and hydration. The epidermis still matters, but the dermis is where a lot of the “support beams” live.

4) Biopsies and injections are planned by layers

Clinicians choose biopsy methods based on how deep they need to sample (top layers vs. deeper structures). Similarly,

injections may be placed intradermally or subcutaneously depending on the goalbecause “location, location, location”

applies to skin too.

Note: This article is educational and not medical advice. If you’re worried about a skin condition, a clinician can help.

Memory tricks without the cringe

Want a fast way to recall the epidermal strata (deep to superficial)? Try this:

- Basale

- Spinosum

- Granulosum

- Lucidum (palms/soles only)

- Corneum

If you prefer superficial to deep, just flip it. Either way, remember the key idea: cells are produced deeper and

migrate upward, becoming more keratinized as they go.

Real-world experiences: what the layers feel like in daily life

Skin anatomy can feel abstract until you connect it to real momentslike the time a paper cut made you question your

life choices, or when winter air turned your hands into a flaky croissant. Here are common, real-world “skin layer”

experiences that help the structure click.

Sunburn: an epidermis lesson you didn’t ask for

After a day outdoors without adequate protection, many people notice redness, warmth, and tenderness firstclassic signs

of superficial injury involving the outer layers. A few days later, peeling often shows up. That peeling is your

body’s way of shedding damaged outer cells and restoring the barrier. It’s not your skin “falling off,” it’s your

epidermis doing a rapid renovation.

Blisters: when friction recruits deeper help

Ever broken in new shoes and ended up with a blister that looks like a tiny water balloon? That often reflects separation

between skin layers due to repeated friction. The “roof” of the blister is protectiveannoying, yes, but it can function

like a natural bandage while the tissue underneath settles down and repairs.

Paper cuts and shallow scrapes: surface drama, quick recovery

Minor abrasions and shallow cuts can sting fiercely even when they don’t bleed much. That’s partly because the skin’s

sensory system is excellent at yelling “Hey!” about small threats. These injuries often heal quickly because they’re

limited to the more superficial zones and don’t destroy as much structural support.

Deep cuts: welcome to the dermis (bring snacks… and maybe stitches)

When a cut extends into the dermis, bleeding is typically more noticeable because this layer contains blood vessels.

Many people also notice that deeper injuries can scar more readily. That’s because the dermis is rich in collagenyour

skin’s scaffoldingand repairs there often involve laying down new collagen in a way that isn’t perfectly identical to

the original architecture. Scar tissue is functional, but it’s not a pixel-perfect restore.

Tattoos: ink lives in the dermis for a reason

Tattoos last because the pigment is placed into the dermis, not the constantly-shedding surface. If ink were placed only

in the epidermis, normal turnover would fade it quickly. The “lasting power” is basically your dermis saying, “Fine,

I’ll hold onto this forever,” like a sentimental friend who keeps concert tickets from 2006.

Dry winter skin: barrier function in the spotlight

When humidity drops, many people experience tightness, flaking, or itchingoften reflecting an irritated or less effective

outer barrier. Moisturizers can help by supporting the outer layer’s ability to hold onto water and feel smoother. The key

takeaway is that “dry skin” is frequently about barrier behavior, not just “needing more water.”

Shots and injections: the hypodermis is a common destination

Some injections are placed into the subcutaneous tissue because it’s a practical space with consistent absorption and a bit

of cushioning. People often describe these as less “sharp” than injections into more sensitive or tightly structured areas.

The hypodermis isn’t numb, but it’s built to be a padding layerso it tends to tolerate certain mechanical stresses better

than the more superficial tissue.

“Why does my face feel different from my feet?”

Many everyday observationscalluses on hands, tougher soles, more delicate eyelid skinmake immediate sense once you remember

thick vs. thin skin. Palms and soles are engineered for friction and pressure; other areas prioritize flexibility, sensation,

or thinness. Same organ, different design specs.

If you’re learning skin anatomy for school, exams, or pure curiosity, these everyday experiences can be the mental hooks that

make the layers stick. Skin isn’t just anatomyit’s anatomy you live in, 24/7.