Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Was Actually Found: Not One City, but a City System

- How LiDAR Finds Cities Under a Rainforest

- Why This Discovery Changes the Amazon Story

- The Upano Valley: Where Volcanoes, Rivers, and People Collide

- How Do You Date a “City” Made of Dirt?

- The Bigger Pattern: Other “Hidden Cities” Across the Amazon

- What “Lost” Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

- Why This Matters Now: Conservation, Ethics, and Urgency

- FAQ: Quick Answers About the “Lost Amazon City”

- Experience: Imagining the Amazon’s “Invisible City” Up Close

- Conclusion: The Amazon Was Never “Empty”We Just Needed Better Eyes

If your mental picture of an “ancient city” includes stone temples, dramatic staircases, and at least one cinematic sunset shotwelcome to the Amazon, where the ruins are mostly dirt, and the drama is hidden under 100 feet of greenery.

The newest headline-grabber isn’t a single crumbling metropolis, but a planned network of ancient settlementscomplete with wide roads, plazas, and thousands of earthen platformsmapped in Ecuador’s Amazon region using LiDAR, a laser-based scanning technology that can “see” the ground through forest canopy.

The result is a discovery that’s both thrilling and oddly humbling: the rainforest isn’t just a wild place people passed through. In many areas, it’s a human-shaped landscapeengineered, managed, and lived in at a scale that surprised even seasoned archaeologists.

What Was Actually Found: Not One City, but a City System

When people say “lost ancient city discovered in the Amazon,” it’s tempting to imagine one lonely, swallowed-by-the-jungle capital. What researchers mapped in Ecuador’s Upano Valley is more like an interconnected urban landscape: multiple population centers linked by straight roads, organized around plazas, and surrounded by intensively used farmland.

The Upano Valley network in plain English

- Thousands of built features (earthen mounds and platforms used for residential and ceremonial structures).

- Plazas and planned layoutsnot random huts, but communities arranged with deliberate geometry.

- Wide, straight roadssome about 10 meters (33 feet) across, extending roughly 10–20 kilometers (6–12 miles).

- A long timeline: occupation associated with the Upano people from around 500 BCE to roughly 300–600 CE.

- Real population scale: estimates suggest at least 10,000 inhabitants, with some scenarios running higher depending on how densely the region was used.

That matters because it pushes back against an old, stubborn story: that Amazonian societies were necessarily small, scattered, and limited by poor soils. What the LiDAR map shows is not “a village.” It’s infrastructure. It’s planning. It’s landscape engineering.

How LiDAR Finds Cities Under a Rainforest

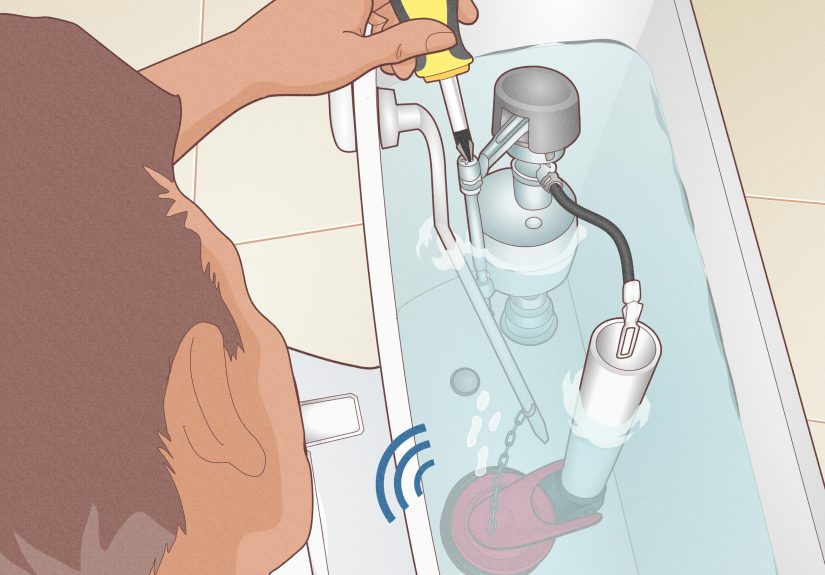

LiDAR (short for “light detection and ranging”) is basically the archaeological version of turning on the lights in a dark roomexcept the “room” is a rainforest the size of a continent.

An aircraft or drone sends out hundreds of thousands (sometimes millions) of laser pulses per second. Some bounce off leaves and branches. A fraction make it through gaps in the canopy and return from the ground.

Why that’s a big deal in the Amazon

In many tropical regions, the hard part isn’t that ruins don’t existit’s that they’re invisible. Forests erase straight lines. Roots blur edges. Time turns platforms into “slightly higher dirt.”

LiDAR lets researchers “digitally deforest” an area and produce a detailed 3D model of the ground surface. That’s how you spot:

- Rectangular platforms that look “too straight” to be natural.

- Raised roadways and causeways that cut across terrain like intentional corridors.

- Plazas and open areas that repeat in a human pattern.

- Drainage canals and agricultural grids that make no sense as random geology.

Important reality check: LiDAR doesn’t “prove” who built something or exactly when. It reveals shapes. Archaeology still needs ground workexcavations, soil studies, radiocarbon dating, and artifact analysisto turn those shapes into history.

Why This Discovery Changes the Amazon Story

1) It challenges the “empty Amazon” myth

For a long time, many textbooks leaned on a convenient assumption: rainforest soils are poor, so large, complex societies couldn’t thrive there. But the Amazon is not one uniform environment, and ancient people were not passive victims of geography.

Discoveries like the Upano Valley network suggest the Amazon contained places where people built long-lasting, organized settlementsand did so in ways that fit local ecology.

2) It upgrades our definition of “a city”

If your only measuring stick is “stone skyscrapers or it doesn’t count,” you’ll miss an entire category of human achievement.

Many Amazonian settlements appear to fit what researchers call low-density urbanism (sometimes framed as “garden” or “agrarian” urbanism): population centers spread out across a managed landscape, with farming integrated into the urban pattern rather than pushed far outside it.

Think of it less like downtown Manhattan and more like a region of neighborhoods, farms, roads, and public spacesplanned, connected, and busywhere the “city” is a system, not a single cluster of buildings.

3) It highlights Indigenous engineering (and yes, it’s engineering)

Roads and plazas are obvious. But the deeper insight is that many Amazonian societies shaped forests and soils over centuries:

managing water, encouraging useful tree species, and creating more productive land without turning the entire region into a moonscape.

The Upano Valley: Where Volcanoes, Rivers, and People Collide

The Upano Valley sits in Ecuador’s Amazon region near the foothills of the Andesa landscape influenced by rivers, slopes, and volcanic activity.

This is not a flat, easy building site. Which makes the scale of human planning even more impressive.

LiDAR mapping revealed complexes of earthen platforms arranged around low squares and plazas, often aligned along broad streets.

The pattern suggests intentional designpublic space, movement corridors, and zones that likely mixed everyday life (homes, craft activity) with communal or ceremonial functions.

And because many structures were built as earthen platforms, they may have served a practical purpose too: elevating living and activity spaces above wet ground, improving drainage, and creating durable foundations in a rainforest environment that loves turning everything into mud.

How Do You Date a “City” Made of Dirt?

Archaeologists don’t date the dirt itself; they date what’s in it and what’s under it.

Common methods used in Amazonian archaeology include:

- Radiocarbon dating of charcoal or organic remains from occupation layers.

- Ceramic analysis: pottery styles change over time, and those changes can be tracked across regions.

- Stratigraphy: reading the sequence of layers to understand building phases and abandonment.

- Soil chemistry to identify long-term human activity (for example, nutrient enrichment).

In the Upano Valley case, the dated occupation range places these settlements across roughly a millenniumlong enough for road systems to be built, maintained, modified, and culturally “normal,” not just a short-lived experiment.

The Bigger Pattern: Other “Hidden Cities” Across the Amazon

The Upano Valley discovery is dramatic, but it isn’t alone. Across the broader Amazon region, LiDAR and satellite imagery have been flipping “unknown” into “mapped” at a rapid pace.

Here are a few examples that help put the newest discovery in context.

Bolivia’s Casarabe culture: pyramids, causeways, and canals

In the Bolivian Amazon (Llanos de Mojos), LiDAR mapping revealed large settlement centers linked to smaller sites by causeways and canals.

Some sites include monumental features such as stepped platforms, U-shaped structures, and conical pyramids reported to reach around 20+ meters in height.

The key concept here mirrors the Upano story: low-density urbanisma built environment spread across a managed landscape, connected by infrastructure, and designed for living with seasonal flooding rather than pretending it won’t happen.

Brazil’s earthworks and “geometric archaeology”

In parts of the southern Amazon, geometric earthworks (often called geoglyphs) have been documentedstraight lines, squares, circles, and connected enclosures visible from above.

Many were first noticed as forests were cleared, which is both scientifically revealing and deeply unfortunate: discovery by destruction is a terrible trade.

The Xingu region: networks rather than lone capitals

Research in Brazil’s Xingu region has also highlighted regional networks of settlements with roads, plazas, and defensive ditchesagain reinforcing the idea that Amazonian complexity often shows up as connected systems, not isolated “one-and-done” cities.

Even colonial-era “lost towns” can reappear

LiDAR doesn’t only reveal ancient Indigenous landscapes. It’s also been used to rediscover remnants of later settlementssuch as colonial-era urban traces hidden by regrowthadding another layer to the Amazon’s long and complicated human history.

What “Lost” Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

Let’s be honest: the word lost is doing a lot of marketing work.

These places weren’t “lost” to the rainforest like a sock behind the dryer.

In many cases, local communities knew the landscape intimately; what was “lost” was broader outside awarenessand the ability of outsiders to recognize earth-and-forest architecture as “real” urbanism.

Also: no, this isn’t proof of a single Amazon-wide empire with one capital and matching uniforms. Amazonian societies were diverse across vast distances.

What the evidence supports is more interesting anyway: multiple complex societies, building in different ways, in different environments, over long stretches of time.

Why This Matters Now: Conservation, Ethics, and Urgency

Archaeology in the Amazon is not happening in a calm museum hallway. It’s happening in a region under pressure from deforestation, development, looting, and fire.

The tragedy is that many archaeological features are shallowroads, ditches, platformsmeaning they can be destroyed quickly by heavy machinery.

Protecting these sites isn’t only about saving the past. It’s also about respecting living communities whose histories and identities are tied to the land.

Ethical research increasingly centers:

- Partnership with Indigenous and local communities, not “parachute archaeology.”

- Site protection and controlled disclosure (because publicizing exact locations can invite looters).

- Conservation planning that treats cultural heritage and biodiversity as linked, not competing goals.

FAQ: Quick Answers About the “Lost Amazon City”

Is it really a city?

It depends on how you define “city.” If you mean planned settlements with roads, plazas, public spaces, and region-wide infrastructure supporting thousands of peoplethen yes, it fits many scholarly definitions of urbanism, especially low-density forms.

How old is it?

The Upano Valley settlement network is associated with occupation from around 500 BCE into the first centuries CE (roughly 300–600 CE for later phases, depending on the area).

Why didn’t anyone see it before?

Dense canopy hides ground features, and earthen architecture weathers into subtle shapes. LiDAR makes those subtle shapes readable at landscape scale.

Does this mean the whole Amazon was densely populated?

Not uniformly. The Amazon includes many environments and histories. The evidence points to pockets of significant population and landscape management, not one single pattern everywhere.

Experience: Imagining the Amazon’s “Invisible City” Up Close

Reading about a “lost city” is fun. Seeing how a “lost city” actually appears in the Amazon is even betterbecause the experience is less like stumbling onto a stone temple and more like learning to read a landscape that’s been whispering history the whole time.

Start with the setting: the Amazon doesn’t greet you with ruins. It greets you with heat, humidity, and an orchestra of soundsbirds calling from somewhere you can’t see, insects that take their job seriously, and wind moving through layers of leaves like a giant, slow exhale.

You could walk past an ancient platform and think it’s just a natural rise in the terrain. That’s the trick. In the rainforest, “obvious” is not a reliable category.

Now picture the LiDAR momentthe part archaeologists often describe with a mix of excitement and disbelief. On a computer screen, the jungle canopy disappears. Not in real life (sadly, you don’t get superpowers), but in data.

The ground surface turns into a clean 3D model. Suddenly, the forest floor isn’t a random green blur. It’s geometry: straight lines, rectangles, wide corridors, repeated shapes that line up like someone planned them with intention.

That’s when the “lost city” stops being a headline and starts being a place with structure.

If you were visiting a research area with guides and local expertise, the experience on foot would be subtle but powerful. A “road” might show up as a long, gently raised band, almost like a natural bermuntil you notice how straight it runs and how it connects to other features.

A “plaza” might feel like an open space where the trees are younger or the ground is flatter than expected.

An “earthen platform” might be a broad, stable rise that makes you think, “Huhif I wanted to stay dry here, this is exactly where I’d build.”

The most meaningful part, though, isn’t the Indiana Jones vibe (which, to be clear, is mostly just sweat and bug spray anyway). It’s the realization that the Amazon holds layered human stories.

The forest can be ancient, and the human presence can be ancient, tooand the two are not automatically enemies.

Many Amazonian societies appear to have managed forests by encouraging useful plants, shaping water flow, and building soils that supported food production.

That reframes the Amazon from “untouched wilderness” to something closer to a cultural landscapealive, biodiverse, and historically inhabited.

There’s also a museum-and-map side of this experience that’s surprisingly emotional. Seeing artifacts like pottery fragments, tools, and soil layers can make the timeline feel real.

A scatter of ceramics isn’t glamorous, but it’s personalevidence of meals, storage, craft, daily life.

And when you pair that with LiDAR imagesroads stretching for miles, mounds in the thousandsyou get a rare combination: the intimacy of human life and the scale of human planning, together in one story.

Finally, there’s the respect piece, which is non-negotiable. These places aren’t treasure boxes; they’re heritage.

A responsible “experience” doesn’t mean grabbing a shovel or hunting for souvenirs (please don’t). It means listening to the people who live in and near these landscapes today, supporting conservation, and understanding why some site details are kept quiet.

In a world where deforestation can erase centuries in a season, the most awe-inspiring part of the “lost city” story might be this: it’s not just being discoveredit’s being recognized, documented, and (hopefully) protected in time.

Conclusion: The Amazon Was Never “Empty”We Just Needed Better Eyes

The “lost ancient city discovered in the Amazon” isn’t one dramatic ruin waiting for a movie poster. It’s something bigger and more important: proof that complex, organized societies lived and built in Amazonia at large scales, designing road networks, public spaces, and productive landscapes that lasted for centuries.

LiDAR didn’t invent that historyit revealed it. And now that we can see these patterns, the challenge shifts from discovery to responsibility: learning the story accurately, avoiding sensationalism, and protecting what remains.