Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Medicare for All, in plain English

- Why the idea keeps coming back

- First: what Medicare is today (and what it isn’t)

- So what does “Medicare for All” actually mean in policy?

- How a single-payer Medicare for All program would work

- 1) Eligibility and enrollment

- 2) Covered benefits

- 3) Premiums, deductibles, copays: what happens to cost-sharing

- 4) What happens to employer-based insurance and private plans

- 5) Networks and “keeping your doctor”

- 6) How providers get paid (and why this is the make-or-break detail)

- 7) Prescription drugs: negotiation, formularies, and the trade-offs

- 8) Administration: fewer payers, fewer rules, fewer billing gymnastics

- How would Medicare for All be financed?

- Transition: the “how do we get there from here?” problem

- Arguments for Medicare for All

- Arguments against Medicare for All (and the trade-offs supporters still have to solve)

- Medicare for All vs. a public option: why the difference matters

- What would Medicare for All change for real people?

- Bottom line

- Experiences: What the Medicare for All debate feels like on the ground (and why people get so passionate)

“Medicare for All” sounds wonderfully simplelike a Costco membership, but for doctor visits. One card. One system.

Fewer forms that ask you to confirm you are, in fact, still you. But the phrase is also famously slippery: people use it

to mean everything from “expand Medicare a bit” to “replace most private insurance with a national single-payer plan.”

This guide breaks down what Medicare for All usually refers to in U.S. policy debates, how a single-payer version would

operate, how it could be funded, and what the real trade-offs look like. We’ll keep it factual, practical, and (as much as

health financing allows) mildly entertaining.

Medicare for All, in plain English

At its core, Medicare for All is the idea that everyone in the United States would be covered by a government-run health insurance program

with a standardized set of benefits. In its most discussed formsingle payerthat public program becomes the primary insurer for medical care, and

most private health insurance for the same basic benefits largely goes away.

Why the idea keeps coming back

The U.S. health system has a few recurring features that make people look for a reset button:

- Coverage gaps (people uninsured, underinsured, or losing coverage when they change jobs).

- Complexity (networks, prior authorizations, surprise bills, and paperwork that could qualify as a minor in accounting).

- Cost pressure (rising premiums, deductibles, and unpredictable out-of-pocket spending).

- Administrative friction (providers billing many payers with different rules, and patients acting as messengers between them).

Medicare for All is often pitched as a way to trade that patchwork for one consistent set of rules and broad coverage.

Whether it succeeds depends on the detailsespecially payment rates, benefit design, and how the country manages the transition.

First: what Medicare is today (and what it isn’t)

Current Medicare is a federal health insurance program mainly for people age 65+ and some younger people with disabilities.

It’s not one single thing; it’s a family of parts and options:

Original Medicare: Parts A and B

- Part A helps cover inpatient hospital care and related services.

- Part B helps cover outpatient care, physician services, and preventive services.

Original Medicare generally involves cost-sharing (deductibles and coinsurance), andcruciallythere’s typically no annual out-of-pocket maximum

unless you have supplemental coverage.

Part D and Medicare Advantage

- Part D adds prescription drug coverage through private plans.

- Medicare Advantage (Part C) lets beneficiaries receive Medicare-covered benefits through private plans instead of traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

So when politicians say “Medicare for All,” they usually mean “a Medicare-like public insurance program for everyone,” not simply “take today’s Medicare,

stretch it like a rubber band, and hope it fits 330+ million people.”

So what does “Medicare for All” actually mean in policy?

In U.S. debates, Medicare for All can refer to:

- A true single-payer plan: one public insurer covers nearly everyone, and duplicates of core benefits aren’t sold as standard private insurance.

- A Medicare buy-in: people can choose to purchase Medicare coverage (often alongside employer coverage and ACA plans).

- A public option: a government-run plan competes with private plans, but does not necessarily replace them.

This article focuses on the version most people picture when they hear the phrase: a national single-payer Medicare for All program.

How a single-payer Medicare for All program would work

1) Eligibility and enrollment

The simplest design is automatic enrollment: if you live in the U.S. (citizen, lawful resident, or defined resident category depending on the bill),

you’re covered. No employer forms. No “open enrollment season” panic. No losing coverage because you changed jobs, started school, divorced,

moved states, or blinked at the wrong time.

2) Covered benefits

Most Medicare for All proposals aim for a broad benefit package. While designs differ, you commonly see coverage for:

- Hospital and physician services

- Preventive care and chronic disease management

- Mental health and substance use treatment

- Prescription drugs

- Dental, vision, and hearing

- Rehabilitative services and sometimes long-term services and supports (LTSS)

The “how” matters as much as the “what.” Covering a service on paper is one thing; having enough clinicians, clinics, and community providers to deliver it is another.

3) Premiums, deductibles, copays: what happens to cost-sharing

A hallmark of many Medicare for All proposals is little to no point-of-care cost-sharingmeaning no premiums, deductibles, or copays for most medically necessary care.

Some designs allow modest cost-sharing for selected items (for example, certain brand-name drugs) to discourage price-insensitive overuse, but this is politically and ethically contested:

cost-sharing can reduce unnecessary care, but it can also reduce necessary care, especially for low-income patients.

4) What happens to employer-based insurance and private plans

Under a true single-payer approach, employer-based insurance would largely be replaced for core medical benefits. Employers wouldn’t be “the place you get your insurance” anymore.

Instead, they’d likely pay some form of tax or payroll contribution that helps finance the system.

Private insurers could still exist, but mainly for supplemental coveragebenefits not included in the public plan (think extra amenities or elective services, depending on program rules).

That’s similar to how some countries with universal coverage still have private add-on insurance markets.

5) Networks and “keeping your doctor”

One of the big selling points is: no narrow networks. In many single-payer designs, you can see any licensed provider that participates in the program.

In theory, that means more choice and less “Sorry, your dermatologist is now out-of-network because your plan had a meeting.”

In practice, provider participation depends on payment levels, administrative rules, and capacity. If a plan pays significantly less than private insurance does today,

some providers may limit the number of program patients they seeespecially in specialties already facing high demand.

6) How providers get paid (and why this is the make-or-break detail)

Single-payer Medicare for All proposals typically rely on a few payment tools:

- Standardized fee schedules for clinicians (often related to Medicare fee-for-service methods).

- Global budgets for hospitals (a yearly budget rather than per-service billing), designed to reduce incentives to maximize volume.

- Negotiated prices for prescription drugs and some services.

The goal is to rein in prices and administrative overhead. The risk is that paying less without planning capacity can create access problems.

A workable design has to balance affordability with maintaining a strong provider networkand build systems for updating rates, measuring quality, and investing in underserved areas.

7) Prescription drugs: negotiation, formularies, and the trade-offs

Medicare for All proposals often assume the public plan can negotiate drug prices more aggressively than the fragmented U.S. payer mix does today.

That can lower spendingbut it may involve tougher formulary decisions, meaning not every drug is covered at any price.

Countries with national systems often pair negotiation power with structured coverage rules and appeals processes.

8) Administration: fewer payers, fewer rules, fewer billing gymnastics

A single national insurer could reduce the complexity providers face when billing dozens of plans with different requirements.

That’s one reason many analyses project potential administrative savings. But “single payer” doesn’t automatically mean “simple.”

The system still needs eligibility systems, claims processing (or budgeting), anti-fraud tools, quality measurement, and pathways for innovation and new treatments.

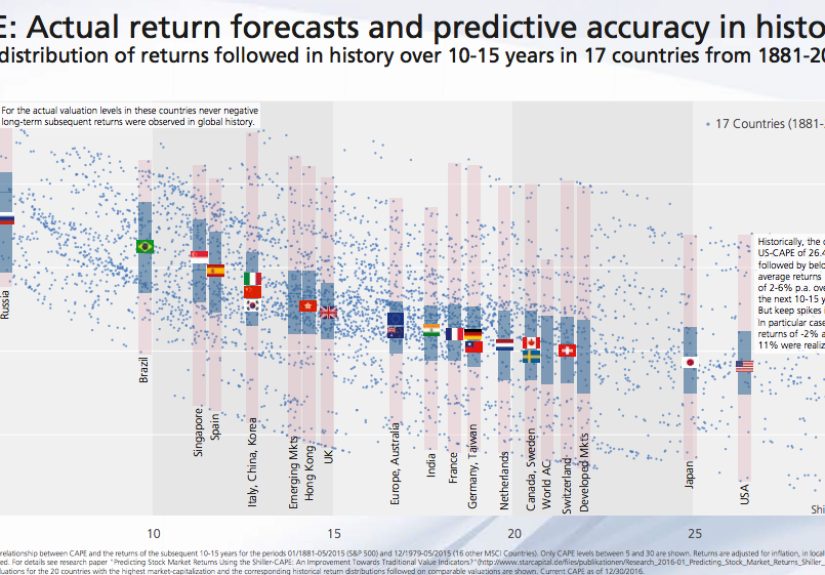

How would Medicare for All be financed?

This is where the conversation often gets dramaticbecause Medicare for All usually means a big shift in who writes the check.

Under a single-payer model, federal spending would rise because the federal government would pay for services currently funded by employers,

households, and state governments. But that does not automatically mean total national health spending rises by the same amountbecause existing spending

(premiums, out-of-pocket costs, employer contributions, and state Medicaid spending) would be replaced by taxes or other public revenue.

Common financing approaches in Medicare for All proposals

- Payroll taxes (paid by employers and/or employees)

- Income-based taxes (more progressive at higher incomes)

- Taxes on capital gains, high-net-worth households, or certain financial transactions (varies by plan)

- Redirecting existing federal and state health spending into the new program

A concrete example: “higher taxes” vs “lower bills”

Imagine a household currently paying $6,000 a year in premiums and another $4,000 in deductibles and copays in a rough year.

Under Medicare for All, that family might pay more in taxesbut far less (or nothing) at the point of care.

The net effect depends on the exact tax design, wages, employer behavior, and the family’s typical health needs.

That’s why cost estimates vary so widely: different analysts make different assumptions about utilization (people using more care once it’s easier to access),

provider payment cuts, administrative savings, and drug pricing. It’s not that math is broken; it’s that the policy choices change the math.

Transition: the “how do we get there from here?” problem

Even supporters agree the transition is the hardest part. Moving from today’s multi-payer system to single payer involves:

- Phasing in coverage (often over several years)

- Shifting millions of people from employer plans, Medicaid, and ACA plans into one program

- Replacing premiums with taxes while preventing gaps in coverage

- Helping workers in insurance-related jobs transition to new roles (administration doesn’t vanish; it changes shape)

- Aligning state budgets if Medicaid funding flows are redesigned

Some legislative proposals include a “buy-in” period or staged eligibility expansion so the system can build capacity before everyone arrives at once.

Think of it as upgrading the plane’s engine while the plane is flyingexcept the passengers are 330 million people and everyone has opinions on the snacks.

Arguments for Medicare for All

Universal coverage and simpler access

The biggest promise is straightforward: everyone is covered, and coverage doesn’t depend on employment, income fluctuations, or state eligibility rules.

That’s a major shift for people who experience coverage churn.

Potential administrative savings

Fewer insurers and standardized rules could reduce billing complexity for providers and reduce time spent fighting denials and navigating plan differences.

Patients may also spend less time sorting out what’s covered and which card to show at which counter.

More bargaining power on prices

A single national insurer could have greater leverage to negotiate drug prices and potentially influence provider pricesespecially in markets dominated by large hospital systems.

Better financial protection

If cost-sharing is minimal, people may face fewer medical debt surprises. That’s not just a household benefit; it can affect labor mobility and entrepreneurship

(people staying in jobs mainly for benefits is a real phenomenon, even if it’s hard to measure cleanly).

Arguments against Medicare for All (and the trade-offs supporters still have to solve)

Taxes would rise, even if total costs don’t

A single-payer plan concentrates spending in the federal budget. Even if households and employers spend less overall on premiums and out-of-pocket costs,

people may experience the change as “higher taxes,” which is politically and psychologically potent.

Provider payment cuts could affect access

Many proposals assume payment rates closer to Medicare’s current levels. That might lower spending, but if rates fall too fastor without targeted investments in workforce and primary care

it can strain access, especially in rural areas or high-cost regions.

Utilization could rise (some of it good, some of it costly)

When coverage becomes universal and point-of-care costs drop, people often use more services. That can be a win if it means earlier treatment and better chronic care.

It can also raise total spending unless offset by price reductions or strong care management.

Implementation is hard, and politics is harder

Medicare for All is a massive redesign touching hospitals, employers, unions, state budgets, and the insurance industry.

Even if a bill passes, the details of regulations, payment updates, and capacity building determine whether real-world performance matches the promise.

Medicare for All vs. a public option: why the difference matters

If Medicare for All is the “replace the plumbing” plan, a public option is the “add another sink” plan.

A public option keeps private insurance but adds a government-run plan on marketplaces (and sometimes for employers), aiming to compete on price and simplicity.

In general:

- Single payer offers maximum standardization and universal coveragebut creates bigger disruption and a larger shift into taxes.

- Public option / buy-in can expand coverage with less disruptionbut may preserve complexity and leave some affordability problems in place.

What would Medicare for All change for real people?

If you have employer insurance

You’d likely stop paying premiums and dealing with plan changes, but you might pay new taxes instead. Your coverage would be portable, not tied to a job.

If you buy coverage on the ACA marketplaces

You’d likely move into a unified plan with standardized benefits and less shopping every year. Subsidy structures would be replaced by the program’s tax financing.

If you’re on Medicaid

You’d likely shift into the national program and avoid state-by-state eligibility differences. That could reduce coverage churn, though benefits and provider access would depend on program design.

If you’re on Medicare today

Your coverage might become richer (for example, adding dental/vision/hearing in some proposals) and your out-of-pocket exposure could change.

Medicare Advantage’s role would likely shrink dramatically in a true single-payer model.

If you’re a clinician or hospital administrator

You might deal with fewer payers and fewer billing rulebooksbut also new budget constraints and different performance measures.

“Less paperwork” is possible, but “different paperwork” is guaranteed.

Bottom line

Medicare for All is not one single blueprintit’s a family of proposals. The single-payer version is the boldest: it aims to cover everyone with a standardized, government-run insurance program,

shift financing from premiums to taxes, and use public bargaining power to lower prices and simplify administration.

Whether it “works” depends on choices that sound technical but shape everyday life: payment rates, benefits, cost-sharing rules, drug negotiation strategy,

provider participation, and the transition plan. It’s a policy argument, yesbut it’s also an operational one. A universal card is the easy part. The system behind it is the real work.

Experiences: What the Medicare for All debate feels like on the ground (and why people get so passionate)

Policy discussions love spreadsheets. Real life loves ambushing you with a broken wrist on a Tuesday. To make Medicare for All feel less like an abstract seminar

and more like something that touches actual humans, here are a few experiencesbased on common, widely reported realities of the U.S. systemshowing why the idea attracts supporters

and why it makes others nervous.

1) The “I have insurance… why am I still scared?” experience

A lot of Americans technically have coverage and still feel one bad medical year away from financial chaos. The stress isn’t just the bill you seeit’s the bill you might see.

You don’t know if a facility fee will appear like a surprise sequel. You don’t know if the anesthesiologist is “in network” even when the hospital is. You don’t know if your plan will

decide that the MRI was “not medically necessary” after your doctor already ordered it and your knee already voted “yes, necessary.”

For people in this situation, Medicare for All is appealing because it offers a different emotional baseline: coverage that doesn’t change when your job changes and

rules that don’t depend on which logo is on your insurance card this year. If cost-sharing is low, it also reduces the “Should I wait and hope this goes away?” habit

which can be tragically expensive in both health and dollars.

2) The small business owner who’s tired of playing HR roulette

Small employers often want to do right by their teams, but offering health benefits can feel like negotiating with a mystery box. Premium renewals arrive, the numbers jump,

and suddenly you’re choosing between raising employee contributions, shrinking benefits, or cutting elsewhere. It’s not that the owner dislikes health careit’s that they didn’t open a bakery

to become an amateur health insurance broker.

A Medicare for All system could change that by moving health coverage out of the employer role entirely: instead of picking plans, managing enrollments, and explaining deductibles,

the business pays a predictable tax contribution (depending on the proposal). That simplicity is a genuine draw. The concern? If the tax is higher than what the business currently pays

(especially for firms that offer lean coverage or none at all), it feels like a new costeven if it’s part of a broader shift that benefits workers and the economy.

3) The clinician who wants to practice medicine, not fax combat

Ask many clinicians what they’d like to do less of, and “fighting with insurance” ranks somewhere between “paper cuts” and “stepping on a LEGO.”

Prior authorizations, claim denials, and different billing rules across plans eat time that could go to patient care. The idea of one payer with standardized rules sounds,

to many providers, like fewer battles and less administrative overhead.

But there’s a second half of that story: payment. Clinicians also worry about a world where one payer sets rates too low, or updates them too slowly, or adds

heavy compliance burdens. In other words, providers may love the idea of fewer payers while fearing the reality of a single payer that’s hard to negotiate with.

A functional Medicare for All design has to make participation worthwhile and keep the care workforce from burning out or shrinking.

4) The chronic condition “full-time patient” perspective

If you manage a chronic illness, you live inside the system year-round. You’re tracking formularies, scheduling specialist visits, and praying your medication stays covered.

Switching insurance can mean rebuilding your care team from scratchnew referrals, new approvals, new “history” that you have to re-tell like a greatest-hits album you didn’t want to record.

Medicare for All is attractive here because it can promise continuity: stable coverage, stable benefits, and a clearer pathway to care. The worry is access constraints:

if demand rises and capacity doesn’t, “covered” doesn’t always mean “available next week.” That’s why serious proposals can’t only focus on financing; they also have to invest in

primary care, mental health providers, rural clinics, and the overall workforce pipeline.

5) The “I don’t trust big systems” gut reaction

Not all hesitation is about math. Some people simply do not want the federal government to be the central organizer of health coverage, even if they dislike the current system too.

They worry about political swings changing benefits, budgets tightening during recessions, or bureaucratic delays. That skepticism is not automatically irrational:

every large systempublic or privateneeds accountability and transparency.

The honest takeaway from these experiences is this: Medicare for All isn’t a magic wand, but it’s also not a fantasy. It’s a trade. It trades the complexity of many payers

for the power (and risk) of one. It trades premiums for taxes. It trades today’s fragmentation for a unified set of rulesthen asks whether we can design those rules well,

fund them fairly, and run the transition without breaking access along the way.