Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Reading Motivation Drops in Middle School

- Core Principles for Motivating Middle School Readers

- 1. Lead with Choice and Voice

- 2. Build a Culture of Reading, Not Just an Assignment

- 3. Make Reading Social and Authentic

- 4. Provide Structure, Goals, and Gentle Accountability

- 5. Harness Gamification and Technology (Without Letting Them Take Over)

- 6. Support Struggling Readers with Scaffolds, Not Shame

- A Sample One-Week Plan to Jump-Start Reading Motivation

- Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Real-World Experiences: What This Looks Like in Classrooms

- Final Thoughts

If you teach middle school, you’ve probably seen it: a student who can spend

45 minutes perfecting a Minecraft world or scrolling TikTok, but “can’t possibly”

read for 10 minutes. Meanwhile, national data show that a growing number of U.S.

students are reading below basic levels in middle grades, with recent reports

highlighting record-low reading scores for eighth graders.

That’s not just a test-score problemit’s a life problem. Reading volume and

reading joy are tightly linked to academic success, future income,

and even long-term health.

The good news: motivation is not fixed. Research on adolescent literacy, classroom

libraries, and public library programs consistently finds that when students

have access to the right books, meaningful choice, positive relationships with

adults, and authentic reading experiences, their desire to read can grow

dramatically.

In other words, middle school doesn’t have to be the place where reading

enthusiasm goes to die.

This guide pulls together classroom-tested strategies and current researchmuch

of it highlighted on Edutopia and similar U.S. education sitesto help you

motivate middle school students to read more, read better, and (yes) actually

enjoy it.

Why Reading Motivation Drops in Middle School

Before we talk solutions, it helps to understand why so many middle schoolers

disengage from reading. Studies of adolescent readers show a pattern: motivation

often declines sharply as students move from elementary to secondary grades.

Identity Is in Flux

Middle school is prime “Who am I?” territory. Students are sorting out their

identities, friendships, and interests. If they don’t see themselvesculturally,

emotionally, or linguisticallyin the texts you provide, reading feels like

someone else’s hobby. Research on classroom libraries and reading engagement

shows that access to diverse, high-interest titles significantly increases

voluntary reading.

Skill Gaps Undermine Confidence

Many students hit middle school with unfinished foundational skills. Recent

literacy reports indicate that a substantial percentage of students are reading

below grade level, and those gaps were widened by pandemic-era disruptions.

When reading feels consistently hard or embarrassing, it’s no surprise that

students avoid it. Motivation and self-efficacy (the belief “I can do this”)

are tightly linkedif students don’t think they can succeed, they won’t try.

Competition from Screens and Short Texts

Middle schoolers live in a world of constant notifications, video feeds, and

10-second clips. Long-form reading has to compete with highly engineered digital

rewards. Research on reading habits notes that many teens spend far more time

on passive media than on extended reading for pleasure, which can gradually thin

their attention span for sustained text.

None of this is an excuseit’s a design challenge. If we want middle school

students to read, we must build classrooms, routines, and communities that make

reading feel meaningful, doable, and worth their time.

Core Principles for Motivating Middle School Readers

Across research and practice, several themes show up again and again. Edutopia

articles on adolescent reading motivation, along with recent studies on

classroom libraries and student choice, emphasize that motivation grows where

students experience autonomy, competence, and connection.

1. Lead with Choice and Voice

One of the strongest findings in the literature: when students have real

choice in what they read, their motivation and time-on-task increase. Research

on independent reading shows that student choice is associated with higher

engagement, persistence, and willingness to tackle challenging texts.

-

Offer wide, inclusive classroom libraries. Stock fiction,

nonfiction, graphic novels, poetry, magazines, and audiobooks. Classroom

library studies find that when students have immediate access to varied,

high-interest books, they read more frequently and for longer periods. -

Normalize “just right for now” books. Teach students that

reading “below level” to rebuild stamina or explore a new genre is not a

downgrade; it’s smart training. -

Use low-stakes book “speed dating.” Give each student a small

stack of books to sample for 2–3 minutes before passing them onan approach

many teachers use to increase exposure and curiosity.

The key is that choice is genuine. “You can read this worksheet or

that worksheet” doesn’t count.

2. Build a Culture of Reading, Not Just an Assignment

Motivation is contagious. When students see classmates, teachers, and librarians

talking about books, making recommendations, and celebrating reading, it becomes

part of the social fabric rather than a solo chore.

-

Make your classroom library a lived-in space. Research on

school and classroom libraries shows that thoughtfully curated, well-used

libraries correlate with higher reading motivation and achievement. -

Partner with your school and public librarians. National

reviews of library programs highlight their role in providing access,

programming, and community that sustain lifelong reading habits. -

Celebrate reading publicly. Think reading walls, student

recommendation displays, book trailers, or “book award” bulletin boards where

students nominate favorites.

3. Make Reading Social and Authentic

Edutopia’s coverage of middle and secondary literacy repeatedly emphasizes

that older students are more engaged when reading leads to authentic talk and

meaningful tasks, not just quizzes.

-

Give time for real book talk. Short, structured conversations

(like partner “book buzzes” or small-group chats) let students process their

reading and borrow ideas from peers. -

Use creative response options. Character monologues, podcast

episodes, digital posters, or mini-comics can showcase comprehension while

tapping students’ strengths. -

Connect reading to life. Invite students to link texts to

current issues, personal experiences, or social media discussions. When a

book feels relevant, motivation rises.

4. Provide Structure, Goals, and Gentle Accountability

Motivation doesn’t mean zero structure. Middle schoolers often benefit from

clear routines and visible progress. Recent Edutopia work on student ownership

of learning highlights how tracking goals can increase engagement and

responsibility.

-

Set personal reading goals, not just class requirements.

Students might track minutes, pages, or completed texts, then reflect on

patterns over time. -

Hold brief reading conferences. Five-minute one-on-one check-ins

allow you to gauge comprehension, suggest next reads, and affirm effort. -

Use simple, flexible reading logs. Skip the “write a paragraph

for every chapter” approach. Instead, try quick jots: date, pages, one

sentence or emoji about how it felt.

5. Harness Gamification and Technology (Without Letting Them Take Over)

Gamification research suggests that leaderboards, badges, and challenges can

boost engagement when used thoughtfully and tied to meaningful learning.

Reading platforms and school or library challenges can transform reading into a

shared game rather than a solitary grind.

-

Run seasonal reading challenges. Think “Mystery March” or

“Graphic Novel November,” with class goals and small celebrations. -

Offer badges for behaviors, not just speed. Honor students

for trying a new genre, finishing a long book, or recommending a title to

someone else. -

Try digital reading and audiobooks for reluctant readers.

Studies of reluctant readers using e-books show improved attitudes and

willingness to engage, especially when devices feel familiar and less

stigmatizing.

6. Support Struggling Readers with Scaffolds, Not Shame

Many middle schoolers who “hate reading” actually hate feeling lost.

Edutopia and other literacy resources emphasize providing multiple entry points:

scaffolded texts, explicit vocabulary support, and targeted small-group work

for students reading below grade level.

-

Offer text sets at various levels so students can access the

same topic or theme with appropriate support. -

Pair print with audio. Listening while following along can

reduce cognitive load and build fluency without watering down content. -

Teach “how to be a reader.” Model thinking aloud, annotating,

and managing confusion. Many students have never seen an adult struggle

productively with a text.

A Sample One-Week Plan to Jump-Start Reading Motivation

To make this concrete, here’s how one week in a middle school English or advisory

class might look if you’re trying to reboot reading motivation:

Monday: Book Tasting and Goal Setting

- Set up “tasting tables” with different genres and formats.

- Give students 3–4 rounds of quick browsing and note-taking.

- Ask each student to choose 1–2 “maybe” books and set a personal reading goal for the week.

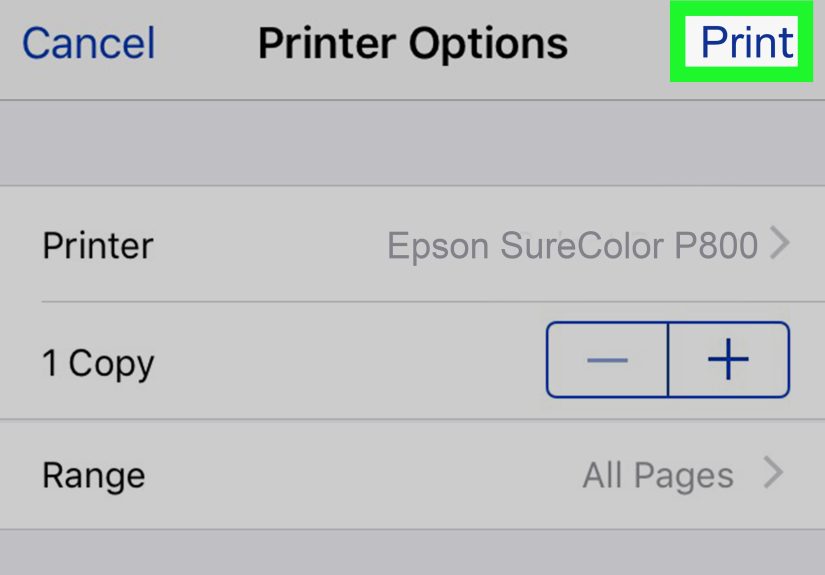

Tuesday: Quiet Reading + Quick Conferences

- Dedicate 15–20 minutes to independent reading.

- Hold short conferences with 4–5 students about their choices and goals.

- Have students record a one-sentence reflection about how their reading went.

Wednesday: Social Book Talk

- Run a “pair and share” where students explain what they’re reading and why.

- Invite a librarian, another teacher, or an administrator to share their current read.

- End with a quick whole-class “book wish list” brainstorm for future purchases.

Thursday: Creative Response

- Ask students to create a mini-book cover redesign, character playlist, or 6-word summary.

- Display the results and allow a short gallery walk.

- Use this work to spotlight diverse titles and voices.

Friday: Gamified Challenge and Reflection

- Celebrate milestonespages read, genres tried, new authors discovered.

- Offer badges or certificates that honor persistence and risk-taking, not just speed.

- Have students reflect: “What helped me read more this week? What should we try next?”

Repeat a version of this structure regularly (weekly or biweekly), rotating

genres and challenges so reading never feels like the same old chore.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Even well-intentioned teachers can accidentally shut down motivation. Watch

out for these traps:

-

Over-policing reading levels. Leveling systems can be useful

tools, but if students are constantly told a book is “too easy” or “too hard,”

they may feel labeled rather than supported. -

Assigning only tests and essays as responses. If every book

leads to a lengthy written assessment, students quickly associate reading

with stress, not curiosity. -

Publicly shaming reading performance. Practices like whole-class

“round robin” reading or posting reading scores on the wall can trigger

anxiety and avoidance, especially for struggling readers. -

Ignoring student feedback. If students say they’re bored with

the available texts or overwhelmed by the workload, that’s data, not defiance.

Real-World Experiences: What This Looks Like in Classrooms

It’s one thing to list strategies; it’s another to watch them play out with

actual middle schoolers. Here are some composite experiences, drawn from

classroom practices and educator reflections, that show what motivating

middle school readers can look like day to day.

In one sixth-grade classroom, the teacher noticed a familiar pattern during

independent reading time: a handful of students buried in their books, a

handful pretending to read, and a sizable group perfecting their “I’m staring

at the page; please don’t notice I haven’t turned it in 12 minutes” face.

Instead of doubling down on reading logs, she started with a simple survey:

“When was the last time you liked something you read?” The answers ranged from

“a soccer article online” to “a horror manga” to “the last time an elementary

teacher read out loud to us.”

She used those responses to overhaul her classroom library, adding more sports

nonfiction, graphic novels, and short, high-interest texts. She also created

a “Not My Thing (Yet)” shelfa home for books students abandoned without being

judged. Within a few weeks, the same students who had resisted reading were

sneaking peeks at books during transitions. The content hadn’t magically

become easier; the environment had become more forgiving and more aligned with

who they were.

Another teacher, working with seventh graders reading below grade level, built

a routine that blended structure and autonomy. Mondays and Wednesdays were

for independent reading with short conferences; Tuesdays were reserved for

guided reading groups on carefully chosen text sets; Thursdays featured

“reading labs” where students rotated through vocabulary games, fluency

practice, and digital reading on tablets with audio support. Fridays became

“Show What You’re Loving” daysstudents could share a quote, a sketch, a

playlist, or even a meme related to their texts.

Over the semester, students’ reading stamina increased, but so did their sense

of ownership. One student, who had loudly announced on day one that he “only

reads subtitles on Netflix,” ended up leading a small group discussion about

a sports biography. When asked what changed, he shrugged and said, “You let

me pick it, and you didn’t make me write an essay after every chapter.”

A different school took a whole-community approach. The middle school librarian

partnered with English, social studies, and science teachers to create a

yearlong “Reading Lives” project. Students kept digital portfolios documenting

what they read inside and outside of schoolnovels, fan fiction, social media

threads, articles, manuals, even game lore. Several times a year, families

were invited to evening “reading showcases” where students shared favorite

texts and recommendations.

Teachers reported that once reading was recognized as something that could

happen in many formats and places, the energy shifted. Students who had never

identified as “readers” suddenly had something to contribute: the graphic

novel expert, the news article hunter, the how-to-manual enthusiast. The goal

wasn’t to convince every student to fall in love with 400-page classicsit was

to show them that reading is already woven into their lives and can be expanded

in powerful ways.

These experiences share a few common threads. Adults listened to students

before redesigning routines. Choice and access were treated as non-negotiables,

not bonuses. Reading was made visible, social, and celebratory. And progress

was measured not only by test scores, but by quieter indicators: students

arguing over who gets a book next, recommending titles to friends, or asking,

“Can I keep reading?” when the period ends. Those small moments are where

motivation takes root.

Final Thoughts

Motivating middle school students to read isn’t about the perfect program or

the trendiest app. It’s about building ecosystemsclassrooms, libraries, and

communitieswhere reading is accessible, affirming, and actually enjoyable.

The research is clear that when students have choice, strong relationships,

rich access to texts, and opportunities to see themselves as capable readers,

motivation can grow even in challenging times.

Start small. Add a few high-interest titles. Carve out 10 more minutes for

genuine reading. Host one low-stress book talk. Ask students what would make

reading feel worth their timeand believe them when they tell you. Those

incremental moves can add up to something powerful: a middle school culture

where students don’t just read because they have to, but because, more and

more, they want to.