Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Pick Your Poker: Scope Is a Feature

- Cards, Decks, and the Art of Not Cheating Accidentally

- Poker Hands in Code: Rankings, Tie-Breakers, and Tiny Technicalities

- Using GPT Help Without Getting “Confidently Incorrect” Code

- Testing Poker Logic: Because “Seems Right” Is Not a Strategy

- Odds, Bots, and Monte Carlo: Let the Computer Sweat

- Multiplayer and Fairness: Where Poker Turns Into Security Engineering

- Common Pitfalls (AKA “How to Invent a Scam by Accident”)

- Conclusion: Build It Like a Dealer, Test It Like a Skeptic

- Bonus: of “I’ve Seen This Movie” Experiences (So You Don’t Star in the Sequel)

Building a poker game is a little like hosting a dinner party for very opinionated mathematicians:

everyone argues about the rules, someone’s always convinced the shuffle is “rigged,” and your app will be blamed

for a bad beat it didn’t cause. The fun part? You get to turn all that chaos into clean, testable code.

The even funner part (yes, funner): using GPT as your co-pilot so you spend less time googling “ace-low straight”

at 2 a.m. and more time shipping.

This guide walks through poker game development from the inside out: modeling cards and a deck, shuffling fairly,

evaluating hands correctly (the part that makes grown engineers cry), testing the logic, and even running Monte Carlo

simulations for odds. Along the way, you’ll see how to ask GPT for help in a way that produces reliable code instead

of “sure, here’s a function that… doesn’t compile.”

Pick Your Poker: Scope Is a Feature

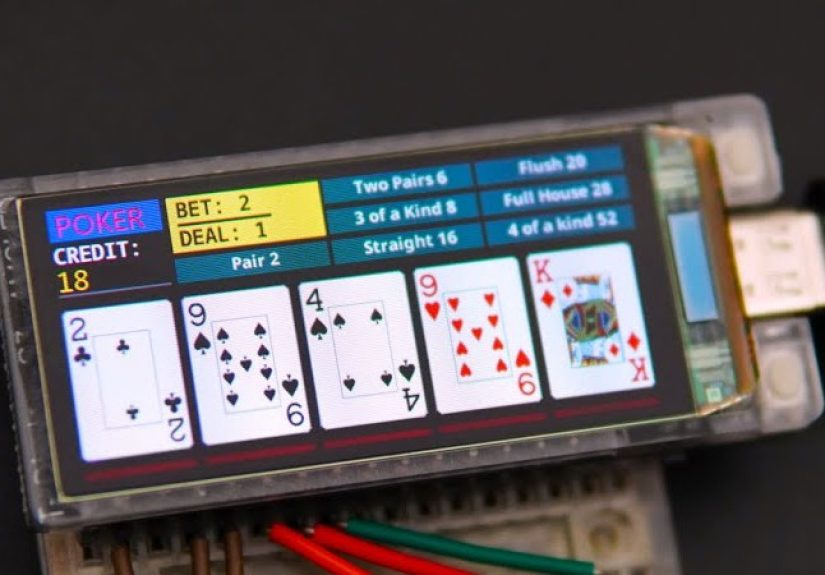

“Poker game” can mean wildly different things. A simple single-player 5-card draw is a great starter:

deal five, allow discards, re-deal, evaluate hand, declare winner. Texas Hold’em adds community cards, betting rounds,

side pots, and the emotional damage of watching your two pair lose to a rivered straight.

A practical MVP (Minimum Viable Poker) usually includes:

- Rules engine: dealing, turn order, betting flow.

- Hand evaluator: “what beats what,” including tie-breakers and kickers.

- RNG + shuffle: unbiased shuffling and predictable behavior in tests.

- State management: table state, player stacks, pot(s), action history.

- UI: even a console UI counts. Poker is surprisingly fun in a terminal.

Cards, Decks, and the Art of Not Cheating Accidentally

Modeling Cards Without Overengineering (Yet)

Keep the data model boring. Boring is good. Boring ships.

A card is a rank and a suit. A deck is 52 unique cards. Your “fancy” starts laterlike when you optimize hand

evaluation or add animations that make players feel like they’re in a heist movie.

Shuffling: Use the Right Algorithm, Not “Random-ish Vibes”

A fair shuffle means every permutation is equally likely. That’s the whole point. The standard approach in software

is the Fisher–Yates (aka Knuth/Durstenfeld) shuffle: iterate from the end and swap each position with a random earlier

position. It’s fast (O(n)) and unbiased when implemented correctly.

If you’re building a local casual game, a standard PRNG is fine. If you’re building anything that resembles

real-money playor even competitive online playuse a cryptographically strong RNG so nobody can predict future cards.

In Python, that typically means secrets or random.SystemRandom.

GPT is great at generating this, but you still need to verify two things:

(1) the range is correct (0..i, not 0..n), and

(2) you’re not introducing bias with something like rand() % (i+1) in languages where modulo bias matters.

Poker Hands in Code: Rankings, Tie-Breakers, and Tiny Technicalities

Every poker variant rides on hand rankings: royal flush down to high card. Texas Hold’em uses seven cards total

(two hole cards + five community cards), but the best hand is still the best five-card combination.

That detail shapes your entire evaluator design.

Two Common Evaluation Strategies

-

Brute-force combinations (simple, correct):

For 7 cards, compute all 21 five-card combinations, rank each, take the best.

This is usually fast enough for hobby games and even many production apps. -

Lookup-table / bit tricks (fast, complex):

Algorithms like the classic “Cactus Kev” approach use precomputed tables and clever encodings to evaluate hands

extremely quickly. Great for simulators and botsbut more work to implement and validate.

For most developers, start with combinations. When you later need speed, optimize with confidence because you’ll

already have a test suite that proves what “correct” means.

A Practical “Rank Tuple” Approach

A clean trick is to have your evaluator return a comparable tuple:

(category, primaryRanks..., kickerRanks...).

The category is an integer where higher means better (e.g., 9 = straight flush, 0 = high card).

The remaining fields break ties in the exact order poker rules require.

The point isn’t that this snippet is “perfect.” The point is the shape: a deterministic ranking output that’s easy

to compare and easy to test. GPT can help you fill in missing cases, but you should treat it like a junior developer:

helpful, fast, and occasionally convinced that a flush beats a full house.

Using GPT Help Without Getting “Confidently Incorrect” Code

GPT shines in poker projects because the domain is rule-based: fixed hand rankings, standard dealing patterns,

predictable state machines. But you’ll get the best results when you prompt like an engineer, not like you’re asking

a magic eight ball.

Three Prompts That Usually Work

-

Make it specify outputs:

“Write a function that evaluates a 5-card poker hand and returns a tuple suitable for comparisons.

Include ace-low straight handling and kicker logic. Provide 10 unit tests.” -

Give constraints:

“No external libraries. Must be deterministic. Must not allocate large tables. Focus on clarity.” -

Use test-first collaboration:

“Here are failing tests. Fix the implementation to pass them without changing the tests.”

Also: ask GPT to explain edge cases in plain English before it writes code. If it can’t describe how it will handle

A-2-3-4-5, ties, and duplicate ranks, you probably don’t want it writing your evaluator yet.

Testing Poker Logic: Because “Seems Right” Is Not a Strategy

Poker is a bug magnet. A single mis-ranked hand can break your game economy, your bot behavior, and your friendships.

Automated tests are non-negotiable.

Parametrized Tests: One Pattern, Many Hands

The best test suites include nasty little realities: duplicated suits, wheel straights, tie scenarios where the

“kicker” decides everything, and Hold’em boards where everyone shares the same best five cards (split pot city).

Odds, Bots, and Monte Carlo: Let the Computer Sweat

Once your evaluator works, you unlock the “fun math” layer: calculating win probabilities. This is where Monte Carlo

simulation earns its keep. Instead of deriving exact combinatorics for every scenario, you simulate thousands (or

millions) of random runouts and measure outcomes. For poker toolslike an odds calculator or a bot’s decision engine

Monte Carlo is often the easiest path to surprisingly strong results.

GPT can help you optimize this (caching, faster card encoding, avoiding object churn), but start with correctness.

“Fast wrong” is just a fancy way to lose money quicklyeven if it’s play chips.

Multiplayer and Fairness: Where Poker Turns Into Security Engineering

Local poker is easy. Online poker is where you discover that “game dev” sometimes means “adversarial systems.”

If players can see or influence the shuffle, you’ve built a magic trick with a suspiciously profitable magician.

- Server-authoritative dealing: clients request actions; the server owns the deck and validates moves.

- Audit logs: keep an action history so disputes can be reviewed (and rage quits can be quantified).

- Stronger randomness: use system entropy sources, and never reuse predictable seeds.

- Cheat resistance: don’t trust the client for anything that matters.

If you’re doing real-money play, you’re in a different universe: compliance, certification, and regulation.

Even for social poker, you’ll borrow the same mindsettransparency, testability, and a paper trail of decisions.

Common Pitfalls (AKA “How to Invent a Scam by Accident”)

1) Biased Shuffles

If your shuffle is wrong, your whole game is wrong. Watch for off-by-one ranges, bad RNG usage, or naive swap loops

that don’t generate uniform permutations.

2) Straight Logic (Ace Is a Drama Queen)

Aces can be high or low, but not both at once. The A-2-3-4-5 “wheel” is the classic bug.

Write tests for it. Write more tests for it. Name one test “please don’t break the wheel again.”

3) Tie-Breakers and Kickers

Two hands can share a category but differ by kicker. If you don’t encode kickers correctly in your ranking output,

your winner logic will be haunted forever.

4) Betting State Machines

Hand evaluation is math. Betting is psychology translated into finite states.

Keep betting logic explicit: states, transitions, and validation. GPT can help draft a state machine, but you must

own the rules.

Conclusion: Build It Like a Dealer, Test It Like a Skeptic

Programming a poker game is a perfect blend of rules, probability, and software design. The deck model and shuffle

get you fairness, the hand evaluator gets you correctness, and the tests keep you honest when you refactor at midnight.

Add GPT help the right wayclear prompts, constraints, and test-driven collaborationand you’ll move faster without

sacrificing reliability.

Start small. Ship a working 5-card evaluator. Then add Hold’em board logic. Then betting rounds. Then odds.

And when your first user complains the shuffle is rigged, smile warmly and point to your test suite like it’s

a security blanket… because it is.

Bonus: of “I’ve Seen This Movie” Experiences (So You Don’t Star in the Sequel)

If you build poker long enough, you collect a greatest-hits album of bugs and facepalms. Not “my personal life”

storiesmore like the universal folklore developers swap over coffee, the kind that starts with “so I thought the

evaluator was done…” and ends with someone rewriting half the codebase.

The most common plot twist is the wheel straight. Everyone remembers that A-K-Q-J-10 is a big deal,

but A-2-3-4-5 is where logic goes to die. A dev will implement “straight = maxRank – minRank == 4” and celebrate.

Then a player shows up with A-2-3-4-5 and your game declares “high card: ace.” Suddenly your app is trending on the

unofficial bug bounty program known as “group chat.” The fix is simple, but the lesson sticks: write the weird tests

first, because the weird hands arrive early and often.

Next comes two-pair tie-breaking. The code “sort pairs descending and compare” sounds obvious until

you realize your data structure is sorting by suit somewhere (why? because humans), or you accidentally compare the

lower pair before the higher pair. Players don’t just notice this. They notice it immediately, loudly, and with

screenshots. Poker players are basically QA engineers with better hoodies.

Then there’s the shuffle conspiracy. Even with a perfect Fisher–Yates implementation, someone will

swear the RNG “feels streaky.” That’s because randomness is streakyclumps happen. The best defense is to

make your shuffle reproducible in tests (seeded RNG) while staying unpredictable in production (system entropy).

Bonus points if you log shuffle seeds server-side for auditsjust don’t leak them to clients unless you enjoy

speedrunning chaos.

GPT-related war story: the “helpful refactor” that subtly changes behavior. You ask GPT to “clean up the evaluator,”

it rewrites three functions, everything looks nicer, and you merge it. Later you discover it “simplified” a rule by

removing kicker comparisons in one edge case. Moral: GPT is an amazing teammate for drafting, but your tests

are the real adult in the room. When you use GPT, ask it to also generate targeted tests, and never accept a refactor

unless it proves equivalence.

Finally: performance. Someone will try to run 2 million simulations and wonder why their laptop sounds like it’s

preparing for liftoff. The fix is almost always boring: encode cards as integers, reduce allocations, precompute what

you can, and profile before optimizing. If you eventually move to a lookup-table evaluator, your existing tests are

what let you do it safelyotherwise you’re just trading one set of mysteries for another.