Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Batteries Fail (And Why It’s So Hard to Catch in the Act)

- The Breakthrough: Freeze-Frame Microscopy Goes Atomic

- What the Atomic Photos Actually Revealed

- How These Images Help Engineers Prevent Failure

- Zooming Out: Atomic Photos Meet X-Rays, AI, and Supercomputers

- So… Are We Now Safe From Battery Failure?

- of Experiences Related to “Atomic Photos of a Failing Battery”

- Conclusion

Batteries are basically tiny apartment buildings for ions. When everything’s going well, lithium checks in, checks out,

and nobody leaves their stuff in the hallway. When things go wrong, the building develops mysterious “spikes,” the walls

start cracking, and suddenly your phone goes from “100%” to “I’m going to take a nap forever” in the time it takes to open TikTok.

For decades, the hardest part of fixing battery failure has been the same problem every mechanic hates: you can’t repair

what you can’t actually see. You could measure voltage drop, track heat, and dissect dead cells afterwardbut the

real drama was happening at a scale smaller than dust, smaller than germs… down at the level where atoms line up like

bricks in a microscopic wall.

That’s why “first atomic photos of a failing battery” isn’t just a flashy headline. It’s a genuine turning point:

researchers finally captured atomic-level images of the structures that can trigger catastrophic failure in next-generation

lithium metal batteriesrevealing what battery breakdown looks like in its original, undisturbed state.

Why Batteries Fail (And Why It’s So Hard to Catch in the Act)

Failure isn’t one problemit’s a messy group chat of problems

A modern rechargeable battery isn’t a single material. It’s a carefully balanced ecosystem:

an anode, a cathode, a separator (a thin barrier that keeps them from touching), and an electrolyte that moves ions back and forth.

During charging and discharging, atoms shift positions, surfaces react, and microscopic layers form and reform.

Over time, tiny changes snowball into big ones: capacity fades, resistance rises, charging slows, and heat becomes harder to manage.

Sometimes the failure is boring (your battery just ages like milk in the sun). Other times it’s exciting in the worst way:

internal short circuits can occur when structures inside the cell bridge the gap between electrodes.

The “invisible villains”: dendrites and the SEI

Two of the most infamous battery troublemakers are:

-

Lithium dendrites thin, finger-like growths that can form during lithium plating. If they reach across the separator,

they can create internal shorts. -

The SEI (solid electrolyte interphase) a thin layer that forms because electrolyte chemistry reacts with the anode surface.

The SEI can protect the electrode… until it cracks, grows unevenly, or becomes unstable.

The tragedy is that these two problems feed each other. An unstable SEI can promote uneven lithium deposition. Uneven deposition

encourages dendrites. Dendrites can rupture the SEI and expose fresh lithium, which triggers more electrolyte breakdown and even more SEI growth.

It’s like trying to patch a pothole while someone keeps inventing new potholes.

The Breakthrough: Freeze-Frame Microscopy Goes Atomic

Why traditional electron microscopy struggled

Electron microscopes are powerful enough to image atomic arrangementsbut batteries are awkward subjects. Lithium metal is highly reactive.

Many battery interfaces are sensitive to air exposure. And worst of all: the electron beam itself can damage or melt delicate battery structures.

So by the time you “look,” the thing you’re trying to study may already be altered.

That’s where cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) changes everything. Cryo-EM flash-freezes a sample so rapidly that

liquids form a glassy, preserved state. The structures don’t have time to rearrange. Reactions slow way down. Beam damage is reduced.

You aren’t studying a battery crime scene after the factyou’re catching the suspect mid-motion.

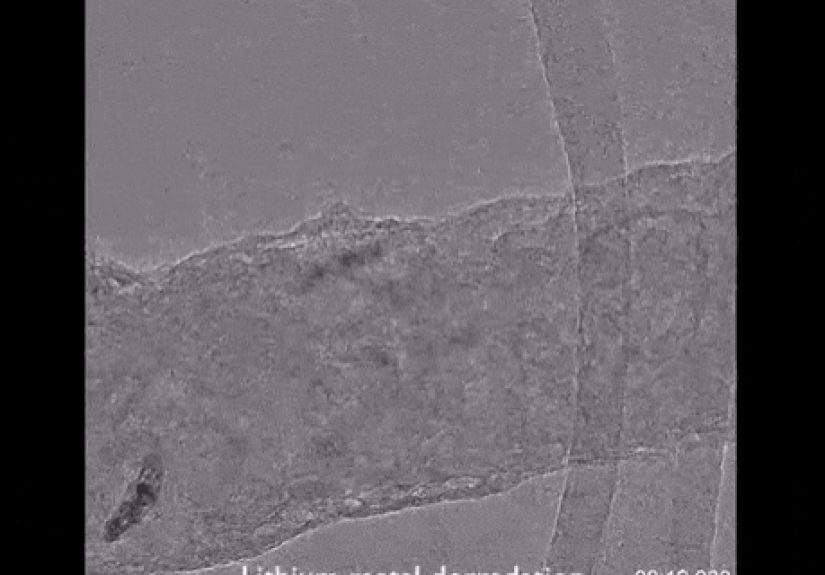

The headline moment: atomic-level images of a failing battery structure

In a landmark study, researchers from Stanford University and the U.S. Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

captured the first atomic-level images of lithium metal dendritesthose finger-like growths that can trigger battery shorts and fires.

Using cryo-EM, they preserved dendrites in a near-native state and imaged them in astonishing detail.

Popular coverage described it simply: “first pictures of a battery failing at the atomic level.” But the science underneath is more thrilling:

atomic-scale imaging revealed that dendrites aren’t just random fuzzthey’re structured crystalline growths with specific shapes and preferred directions.

Once you know the shape and structure, you can start building real, testable strategies to prevent them.

What the Atomic Photos Actually Revealed

1) Dendrites can be crystalline nanowires (not chaotic spaghetti)

The cryo-EM images showed dendrites forming as faceted, single-crystalline nanowires. In other words, atoms weren’t arranged

in a disordered blobthey were lined up in orderly crystal lattices, like a carefully stacked tower.

Even more interesting: dendrites showed preferred growth directions (think “crystal highways”) and could kinkchanging directionwithout obvious

crystal defects. That matters because it hints dendrite growth can be influenced by conditions like current density, electrolyte chemistry,

and surface structure. If growth follows rules, then engineers can design counter-rules.

2) The SEI isn’t just a static “shield”it’s a living, shifting layer

The SEI is sometimes described as the battery’s “skin.” That’s accurate… and also kind of horrifying, because it behaves like skin under stress:

it can swell, shrink, crack, and heal incorrectly.

Later cryo-EM work pushed this even further by imaging SEI layers in a more realistic “wet” environmentcloser to how they exist inside working batteries.

In those conditions, SEI layers can absorb electrolyte and swell, and swelling behavior has been linked to poorer performance in certain systems.

That connection is gold for battery design, because it turns a vague interface mystery into something measurable: chemistry → swelling → performance.

3) “Failing battery” is often an interface story

When consumers think “battery failure,” they picture a dead phone or a car that doesn’t hold range.

But on the inside, the story is often about interfaces:

lithium meeting electrolyte, electrode meeting separator, and tiny layers forming where they touch.

Atomic-level imaging puts those interfaces under a spotlight. It can show where lithium deposits unevenly, how the SEI is structured,

and what changes when conditions shift. That’s a direct path to better materialsand better charging rules.

How These Images Help Engineers Prevent Failure

Designing electrolytes and additives that tame dendrites

Dendrites don’t form in a vacuum; they form in a chemical environment. Changing that environment can change dendrite behavior.

Researchers have explored electrolyte additives that reduce dendrite formation or stabilize the SEIbasically giving lithium fewer bad choices.

One safety-focused line of work investigates adding specific chemicals to electrolytes to suppress dendrite growth. The principle is simple:

if dendrites are fueled by unstable deposition and interface breakdown, then stabilizing that interface can reduce the risk of internal shorts.

Better separators and smarter charging strategies

Even with improved chemistry, battery design still matters. Separators can be engineered for better mechanical resistance,

thermal stability, and ion flow uniformity. Charging protocols can also be adjusted to reduce uneven platingespecially under fast charging,

when gradients inside the cell get more intense.

Atomic photos don’t replace engineeringthey inform it. They tell you whether a “fix” is actually preventing dangerous structures,

or simply pushing them somewhere else.

Zooming Out: Atomic Photos Meet X-Rays, AI, and Supercomputers

Operando X-ray tools: watching batteries while they work

Cryo-EM gives extreme detail, but it often captures snapshots. Meanwhile, large-scale research facilities use advanced X-rays to study batteries

in situ or operandomeaning while they are charging and discharging. This matters because batteries are dynamic systems:

cracks propagate, particles shift, and stress builds over cycles.

Modern X-ray facilities can probe structural changes at fine scales and do it faster than ever, creating massive datasets that show how materials evolve

under realistic conditions. This complements cryo-EM: X-rays reveal broader patterns and evolution; cryo-EM reveals the atomic-level “why.”

AI + imaging: turning pictures into predictions

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: imaging can outpace understanding. You can collect breathtaking atomic-scale data and still struggle to interpret it.

That’s why teams have begun combining machine learning with imaging to identify patterns that correlate with degradation and failure.

For example, researchers have used AI to analyze huge sets of atomic-scale images in lithium-ion materialshelping explain how microfractures form,

how particles degrade, and why certain chemistries age differently. When you combine these approaches, you get a clearer path:

understand the failure mechanism, then design materials and controls to avoid it.

So… Are We Now Safe From Battery Failure?

Not instantly. Atomic photos don’t magically make your old laptop battery immortal. But they do something arguably more important:

they turn battery failure into a problem with visible mechanisms and testable hypotheses.

Instead of guessing whether dendrites are forming, researchers can see their structure. Instead of assuming what the SEI looks like,

they can image it in conditions closer to real operation. Instead of relying only on post-mortem disassembly, they can preserve fragile interfaces

before they change. That’s how engineering leaps happen: fewer myths, more measurements.

of Experiences Related to “Atomic Photos of a Failing Battery”

If you’ve ever owned a phone for more than two years, you’ve probably had your own low-budget, real-life battery study:

the “Why is my battery at 12% already?” experiment. Real-world battery failure is usually quiet at first. You notice range dropping.

Charging takes longer. The device gets warm in situations where it never used to. Then the weird habits start: your battery percentage

falls off a cliff at 30%, like it just remembered it left the stove on and sprinted out of the room.

Those everyday experiences map surprisingly well to what researchers hunt for at the atomic scale. When a battery loses capacity,

something inside it has become less efficient at storing and moving ions. That can mean active material is no longer participating,

interfaces have thickened, or internal resistance has climbed. On the outside, it feels like “my battery got lazy.”

On the inside, it’s more like “the hallways got blocked and the doors got sticky.”

People who fast-charge constantly often report a different flavor of aging: more heat, more rapid loss of peak capacity, and more “battery anxiety”

over time. Engineers see fast charging as a stress test because higher currents can amplify uneven ion flow and surface reactionsexactly the kind of

conditions that can encourage irregular deposition. In the lab, researchers replicate these stresses on purpose: they cycle cells rapidly,

hold them at high states of charge, and push materials until degradation becomes obvious.

In research settings, the “experience” of a failing battery is less about user frustration and more about detective work.

Scientists run controlled cycling tests, track voltage curves, and watch for signatures of increasing resistance.

Then comes the moment that used to be the most disappointing: taking the cell apart and realizing the most delicate structures changed during handling.

That’s why cryo-EM feels like a superpower. Freezing preserves the evidence before it can be disturbed.

There’s also an emotional experience tied to this researchbecause it connects directly to safety. When you read about recalls or battery incidents,

it can feel random and scary. Atomic imaging helps shrink that fear into something tangible: failure often begins with specific structures,

in specific places, under specific conditions. That doesn’t guarantee perfection, but it does mean “battery safety” is no longer just about warnings

and protective circuits. It’s about designing interfaces that don’t grow needles, electrolytes that don’t self-sabotage, and materials that age

gracefully instead of dramatically.

And for everyday people, that future looks like this: fewer surprises, longer lifetimes, faster charging with less stress, and devices that don’t turn

battery ownership into a daily negotiation. It’s hard to get excited about atoms you can’t seeuntil you realize those atoms decide whether your car

goes 320 miles or 220, whether your phone lasts all day or all morning, and whether “charging” feels safe or suspicious.

Conclusion

The first atomic-level photos of battery failure weren’t just a scientific flexthey were a practical breakthrough. By using cryo-EM to preserve and

image delicate battery structures in near-native conditions, researchers revealed the true nature of lithium dendrites and the complex, shifting behavior

of the SEI layer. Those insights turn failure from a mysterious outcome into a visible mechanismsomething engineers can design against.

Combine atomic snapshots with operando X-ray tools, AI-driven image analysis, and high-powered simulation, and you get a new era of battery research:

not just “build and test,” but “see, understand, and prevent.” The end goal is simple: batteries that last longer, charge faster, and fail less

dramaticallyso your devices can stop behaving like they’re auditioning for a soap opera.