Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What is Salmonella?

- How common is Salmonella infection?

- How do people get Salmonella?

- What are the symptoms of a Salmonella infection?

- How soon do symptoms start, and how long do they last?

- Who is at higher risk for severe Salmonella illness?

- When should I see a doctor or go to the emergency room?

- How is Salmonella diagnosed?

- How is Salmonella treated?

- Can Salmonella cause long-term complications?

- How can I prevent Salmonella at home?

- Is it safe to eat raw cookie dough, runny eggs, or sushi?

- Should I worry about Salmonella outbreaks in the news?

- Key takeaways

- Real-world experiences and lessons learned about Salmonella (500-word segment)

Salmonella has a reputation for ruining picnics, summer barbecues, and the occasional batch of “totally safe” cookie dough. But beyond the horror stories, what is it really, how worried should you be, and what can you do to protect yourself and your family?

This Salmonella FAQ walks you through the essentials: what it is, how it spreads, common symptoms, when to see a doctor, and smart everyday prevention tips. It’s friendly, practical, and a little bit lightheartedbut still grounded in real guidance from major U.S. health organizations like the CDC, FDA, Mayo Clinic, and Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Important: This article is for general information only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you think you have a serious infection or feel very unwell, contact a healthcare provider or emergency services right away.

What is Salmonella?

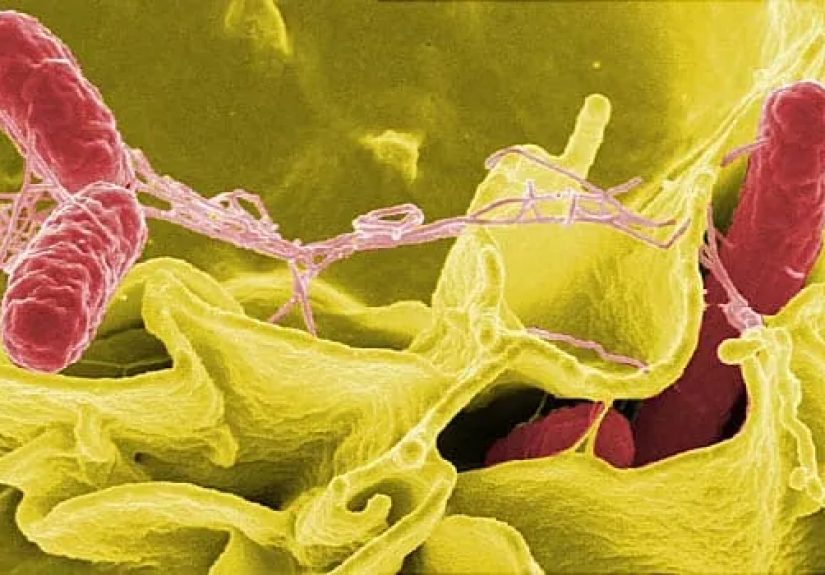

Salmonella is a group of bacteria that live in the intestines of animals and humans. When these bacteria contaminate food, water, or surfacesand then make their way into your mouththey can cause an infection called salmonellosis, a type of foodborne illness that typically affects your intestinal tract.

For most people, Salmonella infection means a few very unpleasant days of diarrhea, cramps, and fever. But in some cases, especially in vulnerable groups, it can become severe and even life-threatening if the bacteria spread beyond the intestines into the bloodstream and other organs.

How common is Salmonella infection?

Salmonella is a big player in the world of food poisoning in the United States. The CDC estimates that each year, it causes about 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and around 420 deaths. Most of these illnesses are linked to contaminated food.

In fact, Salmonella is one of the leading causes of foodborne illness and the leading cause of hospitalizations and deaths from food poisoning in the U.S.

How do people get Salmonella?

You don’t “catch” Salmonella from thin airit usually rides in on something you eat, drink, or touch. Common sources include:

- Raw or undercooked meat and poultry (like chicken, turkey, ground beef).

- Raw or undercooked eggs and foods made with them (cookie dough, homemade mayonnaise, certain desserts).

- Unpasteurized milk and dairy products.

- Raw fruits and vegetables that were contaminated somewhere along the way (in the field, during processing, or in your own kitchen).

- Contaminated water, especially when sanitation systems are poor.

- Contact with animals, especially reptiles, amphibians, backyard poultry, and petting-zoo animals.

- Person-to-person spread when someone infected doesn’t wash their hands properly after using the bathroom, changing diapers, or cleaning up after pets.

Basically, anywhere feces from an infected human or animal can touch food, water, hands, or surfaces, Salmonella can hitch a ride.

What are the symptoms of a Salmonella infection?

Most people with Salmonella develop a cluster of symptoms that look a lot like a bad stomach bug. Typical symptoms include:

- Diarrhea (sometimes watery, sometimes with mucus or even blood).

- Fever.

- Stomach cramps or abdominal pain.

- Nausea and vomiting in some people.

- Headache and general fatigue.

Some people infected with Salmonella may have very mild symptomsor even no obvious symptoms at allbut can still shed the bacteria and infect others.

How soon do symptoms start, and how long do they last?

The incubation periodthe time from swallowing the bacteria to feeling sickis typically between 6 hours and 6 days, with many people getting sick within 12–72 hours.

For most healthy people, symptoms last about 4–7 days. Diarrhea may be the last symptom to resolve and can hang on a bit longer in some cases.

Who is at higher risk for severe Salmonella illness?

While anyone can get Salmonella, certain groups are more likely to develop severe illness or complications:

- Infants and young children.

- Older adults.

- People with weakened immune systems (for example, from cancer treatment, HIV, organ transplants, or certain medications).

- People with chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, or underlying digestive diseases.

- Pregnant people, whose immune changes and pregnancy itself can raise the risk of more serious infection.

In these higher-risk groups, Salmonella is more likely to spread from the intestines into the bloodstream, which is a medical emergency.

When should I see a doctor or go to the emergency room?

Mild Salmonella infections often get better on their own. However, you should contact a healthcare provider if you or someone you care for has:

- Diarrhea lasting more than a few days without improvement.

- High fever (for example, above 102°F / 38.9°C).

- Signs of dehydration (very dry mouth, dizziness, little or no urination, dark urine).

- Bloody stools.

- Severe stomach pain that doesn’t ease.

- Symptoms in an infant, older adult, pregnant person, or someone with a weak immune system.

Seek emergency care immediately if you notice confusion, difficulty breathing, chest pain, fainting, or signs of severe dehydration.

How is Salmonella diagnosed?

Doctors don’t diagnose Salmonella just by “vibes.” They usually confirm it with a stool sample that is sent to a lab to look for the bacteria. In more serious cases, especially when a bloodstream infection is suspected, they might also take blood cultures.

Public health labs can further test these samples to identify the specific strain of Salmonella, which helps track outbreaks and figure out which foods or locations are involved.

How is Salmonella treated?

The good news: most people with Salmonella get better with rest and fluids alone. The bad news: those days may still feel very long.

Treatment usually focuses on:

- Hydration: Drinking plenty of fluidswater, oral rehydration solutions, brothsto replace what’s lost through diarrhea and vomiting.

- Gentle diet: Small, bland meals as tolerated (think toast, rice, bananas), avoiding greasy or very sugary foods while your stomach is upset.

Antibiotics are not needed for most healthy people with mild illness. In fact, using them when they’re not needed can prolong the carrier state or contribute to antibiotic resistance. However, doctors may prescribe antibiotics if:

- The infection is severe.

- The bacteria have entered the bloodstream.

- The patient belongs to a high-risk group (infants, older adults, immunocompromised, etc.).

Over-the-counter anti-diarrheal medications may be used cautiously in some adults, but the CDC recommends calling a doctor first because some of these medicines can prolong illness in certain infections.

Can Salmonella cause long-term complications?

Most people fully recover from Salmonella without lasting problems. However, some individuals develop complications, especially if the bacteria spread beyond the intestines.

Possible complications include:

- Severe dehydration requiring IV fluids or hospitalization.

- Bloodstream infection (septicemia), which can affect the heart, bones, joints, or other organs.

- Reactive arthritis, a type of joint inflammation that can develop after infections like Salmonella, causing joint pain, swelling, and sometimes eye or urinary symptoms.

- Rarely, infection in blood vessels or other serious body sites, especially in people with underlying health problems.

If you’ve had Salmonella and later develop persistent joint pain, eye problems, or urinary symptoms, check in with your healthcare provider and mention your previous infection.

How can I prevent Salmonella at home?

Preventing Salmonella is mostly about good food handling and hygiene. Think of it as a four-part strategy: Clean, Separate, Cook, Chill.

1. Clean

- Wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before and after handling food, after using the bathroom, after changing diapers, and after touching animals or their environments.

- Wash cutting boards, utensils, and countertops with hot, soapy water after they’ve touched raw meat, poultry, eggs, or unwashed produce.

2. Separate

- Use separate cutting boards for raw meats and ready-to-eat foods like salads and bread.

- Keep raw meat, poultry, and seafood away from other groceries in your shopping cart and refrigerator.

3. Cook

- Use a food thermometer to cook foods to safe internal temperatures (for example, poultry to 165°F).

- Avoid runny eggs, undercooked poultry, and burgers that are still pink in the center if you want to minimize your risk.

4. Chill

- Refrigerate leftovers within two hours (one hour if it’s very hot outside).

- Don’t leave perishable foods out on the counter all afternoon during parties or picnics.

On top of this, be especially careful around backyard poultry, reptiles, and amphibians, which can carry Salmonella even when they look healthy. Wash hands thoroughly after handling these animals, and keep them away from kitchens and areas where young children crawl or play.

Is it safe to eat raw cookie dough, runny eggs, or sushi?

Let’s address the heartbreak first: yes, raw cookie dough with eggs can carry Salmonella. So can runny eggs, unpasteurized milk products, and other undercooked animal foods.

To reduce your risk:

- Choose heat-treated flour and doughs that are made without raw eggs if you really love eating dough by the spoonful.

- Use pasteurized eggs or egg products for recipes that stay raw or lightly cooked (like some sauces or desserts).

- Make sure animal-based sushi and other raw foods come from reputable sources that follow strict food safety standards (note that raw seafood has its own set of risks, separate from Salmonella).

Everyone has a different level of risk tolerance, but people in high-risk groups (young children, older adults, pregnant people, and immunocompromised individuals) are generally advised to avoid raw or undercooked animal products.

Should I worry about Salmonella outbreaks in the news?

You’ll often hear about Salmonella outbreaks linked to particular foodsanything from leafy greens to peanut butter to frozen meals. When public health officials spot a pattern of illness, they investigate, identify the food involved, and issue alerts or recalls.

The FDA and CDC maintain online lists of ongoing and past outbreaks. If a product you have at home is recalled because of Salmonella:

- Stop eating or serving it right away.

- Follow instructions in the recall (often to throw it away or return it).

- Clean any surfaces, containers, or utensils that may have touched the product.

Outbreak news can be unsettling, but they’re also a sign that public health systems are actively monitoring food safety and working to protect consumers.

Key takeaways

- Salmonella is a common cause of foodborne illness that usually causes diarrhea, cramps, and fever but can sometimes be severe.

- Most healthy people recover without antibiotics, but dehydration and complications are possible.

- Good hygiene and safe food handlingclean, separate, cook, chillgo a long way in preventing infection.

- Higher-risk groups should be especially careful with raw or undercooked animal products and seek medical care promptly if they get sick.

Think of Salmonella as that uninvited guest who shows up whenever food safety slips. If you keep your kitchen clean, cook foods thoroughly, and wash your hands like you mean it, you dramatically lower the odds of it dropping by.

Real-world experiences and lessons learned about Salmonella (500-word segment)

Statistics and guidelines are helpful, but sometimes what really sticks are the storiesthe “I’ll never do that again” moments that turn into lifelong food safety habits. Here are a few composite experiences (inspired by real-world patterns described by health organizations) that show how Salmonella infections often happen and what people learn from them.

The backyard barbecue wake-up call. Imagine a summer cookout: burgers on the grill, potato salad on the picnic table, kids running around. The grill master is juggling conversation, music, and flipping patties. In the rush, he uses the same plate for the cooked burgers that he used for the raw ones“just for a second.” The burgers move from that plate to everyone’s buns, and by the next day several guests are dealing with diarrhea, cramps, and fever.

When the doctor orders a stool test and confirms Salmonella, everyone is surprised. The cookout “felt” safefood looked done, nobody noticed anything weird. The lesson that sticks: it’s not only about how food looks; it’s about cross-contamination. After that, the host buys color-coded cutting boards, keeps a separate clean plate for cooked foods, and starts using a thermometer instead of guessing doneness from color. That one miserable long weekend permanently upgrades his food safety game.

The “healthy” raw-milk experiment. Another story starts with someone trying to “eat cleaner” and “get back to nature.” A friend raves about raw (unpasteurized) milk from a local farm, saying it’s more natural and full of beneficial nutrients. Curious, they switch to raw milk and use it in smoothies. A week later, they’re knocked flat with severe diarrhea and fever. Diagnostic testing reveals Salmonella, and they end up needing IV fluids in the hospital.

They later learn that unpasteurized dairy products are well-known sources of bacteria like Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria, and that pasteurization is precisely what makes milk much safer without significantly changing its nutritional profile. The big takeaway: “natural” doesn’t always mean “safe,” and food safety regulations are often written in response to very real outbreaks and tragedies.

The adorable-but-germy pet. Picture a family that adopts a small turtle for their child. The turtle quickly becomes the star of the househandled, kissed, and occasionally allowed to roam on the kitchen counter “just for a moment.” Weeks later, the child develops diarrhea and fever and is eventually diagnosed with Salmonella. The public health team asks about pets, and when they hear “small turtle,” alarms go off.

The family learns that reptiles and amphibians commonly carry Salmonella, even when they look perfectly healthy. They also find out that young children are at higher risk for severe illness from these infections. The turtle isn’t necessarily “bad,” but it requires careful handling: washing hands after touching it, keeping it away from food areas, and limiting contact with young children. The family keeps the pet but changes how they interact with itand they become vocal advocates for pet hygiene among friends.

The “mystery salad” at the office. Finally, consider a group of coworkers who all get sick after eating at the same restaurant. The culprit turns out to be a salad mix contaminated before it even got to the kitchen. The restaurant was following basic hygiene, but the contamination happened earlier in the supply chain. An outbreak investigation helps identify the product, and a recall is issued.

For the diners, it’s a reminder that even when they personally do everything “right,” there’s always some residual risk in a complex food system. That said, the experience also highlights why reporting illnesses and cooperating with public health investigations matters. Their willingness to answer detailed questions about what they ate helps stop more people from getting sick.

Across all of these experiences, a pattern emerges: nobody planned to get Salmonella. In each case, people made decisions that seemed harmless or reasonable at the time. The silver lining is that once someone goes through a Salmonella infectionwhether mild or severethey almost always emerge with a much sharper sense of how food safety, animal contact, and hygiene really work in everyday life. And those lessons, shared with family and friends, prevent more cases than any single pamphlet ever could.