Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Dependable” Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

- The Many Cycles Hiding Inside “The Cycle”

- 1) The Business Cycle (the economy’s breathing pattern)

- 2) The Earnings Cycle (companies’ profit seasons)

- 3) The Credit Cycle (when lending gets easy… until it isn’t)

- 4) The Valuation Cycle (how much investors are willing to pay)

- 5) The Sentiment Cycle (feelings, but with Bloomberg terminals)

- 6) The Leadership Cycle (what’s hot changes)

- Why Cycles Keep Happening (Spoiler: It’s Us)

- The Big Mistake: Treating Cycles Like Clocks

- How to Use Cycles Without Becoming a Market Fortune Teller

- A Practical Cycle-Resistant Checklist

- Specific Examples: How Cycles “Rhymed” Without Repeating

- The Dependability of Cycles Is Actually Good News

- Experiences Related to the Dependability of Cycles (Real-World Patterns Investors Live Through)

- Experience #1: “I checked my account and became a philosopher.”

- Experience #2: The performance-chasing loop

- Experience #3: The rebalancer who felt silly (until they didn’t)

- Experience #4: The “cash forever” friend

- Experience #5: The steady contributor who “accidentally” did it right

- Experience #6: The business owner’s cycle lesson

- Conclusion: Plan for the Cycle, Not the Headline

Markets don’t come with a calendar invite. There’s no push notification that says, “Reminder: the next recession starts Tuesday at 2:00 PMbring snacks.”

But there is one thing you can count on: cycles. Not the “everything repeats perfectly” kind (that’s astrology for spreadsheets), but the

“human beings + money + uncertainty = patterns” kind.

If you’ve ever watched a hot investment theme turn into a lukewarm leftoveror felt the emotional whiplash from “to the moon” to “sell everything, move

to a cabin”you already understand the core idea behind The Dependability of Cycles: change is the constant. And if you plan for it,

you don’t have to fear it.

What “Dependable” Really Means (and What It Doesn’t)

Calling cycles “dependable” can sound like a promise: “Don’t worry, the market will do this next.” That’s not the point. Cycles are dependable

in the same way weather is dependable. You don’t know the exact day it’ll rain, but you’d be a little bold to throw away your umbrella forever.

In investing, “dependable cycles” means you should expect:

- Periods of expansion (good times, improving data, rising confidence)

- Periods of contraction (slower growth, tighter conditions, nervous headlines)

- Leadership changes (yesterday’s winners don’t always stay winners)

- Emotional swings (fear and greed take turns driving the bus)

What it does not mean: you can precisely time tops and bottoms, rotate flawlessly between asset classes, or predict next quarter’s GDP with the

accuracy of a Swiss watch. Cycles are reliabletiming them is not.

The Many Cycles Hiding Inside “The Cycle”

People say “the market is cyclical” like it’s one big loop. In reality, it’s more like a messy family reunion of cycles happening at the same time,

occasionally arguing in the driveway.

1) The Business Cycle (the economy’s breathing pattern)

The classic storyline: expansion, peak, recession, trough, repeat. But in real life, it’s less “smooth four-act play” and more “improvised theater with

surprise plot twists.”

Businesses hire, consumers spend, credit flows, and optimism risesuntil constraints show up (inflation, higher rates, overcapacity, falling margins,

layoffs, tighter lending). Then the economy slows, resets, and eventually rebuilds.

2) The Earnings Cycle (companies’ profit seasons)

Corporate profits tend to rise and fall with demand, costs, pricing power, and financing conditions. Even great businesses aren’t immune to margins

compressing when input costs spike or customers pull back.

3) The Credit Cycle (when lending gets easy… until it isn’t)

Credit is the market’s oxygen. When it’s plentiful, it fuels growth, risk-taking, and deal-making. When it tightens, leverage becomes a headache, and

“creative financing” suddenly stops sounding creative.

4) The Valuation Cycle (how much investors are willing to pay)

Sometimes markets don’t move because earnings changedthey move because the price multiple investors will pay changes. Optimism expands

valuations; pessimism compresses them. The same company can look “cheap” or “expensive” depending on whether investors are wearing rose-colored glasses

or doom goggles.

5) The Sentiment Cycle (feelings, but with Bloomberg terminals)

Investor psychology is not a straight line. Confidence builds, narratives harden, and eventually everyone starts believing the same thing at the same

timeright before reality reminds us that certainty is overrated.

6) The Leadership Cycle (what’s hot changes)

Sectors and styles rotate. Growth leads, then value leads. Big companies dominate, then smaller ones catch up. U.S. leads, then international leads.

Sometimes the rotation is slow. Sometimes it feels like musical chairs with a fog machine.

Why Cycles Keep Happening (Spoiler: It’s Us)

If cycles were caused by a single villain, we’d just remove the villain. But cycles persist because they come from normal forces:

- Human behavior: Overconfidence in booms, overreaction in busts, and lots of “this time is different” energy.

- Incentives: When things work, people copy them. That crowding can sow the seeds of the next reversal.

- Constraints: Inflation, capacity limits, wage pressure, and policy responses eventually matter.

- Mean reversion: Extreme conditions tend to pull forward future outcomesgood or bad.

- Uncertainty: The future is unknowable, so narratives compete to explain it. Narratives are… not always stable.

The punchline: cycles don’t require bad people or dumb investors. They can happen in a world full of smart professionals, advanced math, and high-speed

tradingbecause the system is complex and humans are human.

The Big Mistake: Treating Cycles Like Clocks

Most investing pain doesn’t come from cycles existing. It comes from pretending we can predict them with precision. Investors often do one of these:

- Sell after the drop because “it feels safer now” (translation: fear is driving the decision).

- Buy after the run-up because “it’s working” (translation: greed is driving the decision).

- Switch strategies constantly because patience is hard and FOMO is loud.

The cruel irony is that the best investment decisions often feel uncomfortable in the moment. Buying when prices are down feels like catching a falling

knife. Selling a winner to rebalance feels like leaving a party when the music is good. But discipline is basically “doing the reasonable thing while your

feelings file a formal complaint.”

How to Use Cycles Without Becoming a Market Fortune Teller

You don’t need a crystal ball. You need a process. The goal isn’t to outguess every turning point; it’s to make your plan resilient across the whole loop.

Build a portfolio that assumes bad years will happen

A portfolio that only works in perfect conditions is not a portfolioit’s a wish. Start with an allocation you can stick with through volatility.

If a normal drawdown would make you abandon the plan, the plan is too aggressive.

Diversify like you mean it

Diversification isn’t exciting. It’s rarely the hero in a bull market. But it’s often the reason you survive long enough to enjoy the next one.

Owning assets that don’t all suffer at the same time can reduce the odds you panic at the worst possible moment.

Rebalance: the polite way to “buy low, sell high”

Rebalancing is a rules-based way to trim what grew and add to what laggedwithout pretending you know what happens next. It’s not magic, and it doesn’t

guarantee higher returns. But it can help manage risk and reduce emotional decision-making.

If you want rebalancing to actually happen, consider automating it (through target-date funds, balanced funds, or a set schedule). The best rebalancing

plan is the one you’ll do when it’s awkward.

Use contributions as your superpower

Regular investing (like retirement contributions) turns volatility from an enemy into a weird coworker you tolerate because they’re occasionally useful.

When prices drop, your ongoing contributions buy more shares. That’s not a slogan; it’s mechanics.

Keep a “don’t panic” buffer

A modest cash reserve for near-term needs can reduce the pressure to sell investments during downturns. Think of it as emotional insurance:

you’re buying the ability to wait.

Write a one-page investing policy for Future You

Future Youunder stress, doom-scrolling, convinced the world is endingshould not be inventing a plan on the spot. Write down:

- Your target allocation

- When you’ll rebalance (calendar-based, threshold-based, or both)

- What would justify a real change (not “vibes,” not “headlines”)

- What you will not do (like selling everything because your group chat is panicking)

A Practical Cycle-Resistant Checklist

When things feel amazing

- Check your risk. If your portfolio quietly became “all the hottest stuff,” rebalance.

- Assume good news is already priced in more than you think.

- Don’t confuse a great market with personal genius.

- Keep saving. The goal is progress, not bragging rights.

When things feel terrible

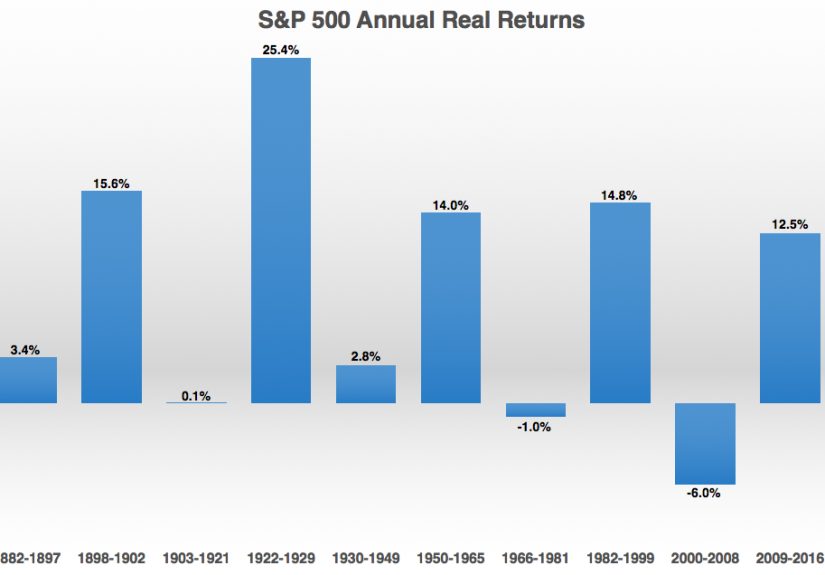

- Zoom out. Markets have lived through wars, inflation, bubbles, and bad hair decades.

- Review your time horizon. If you don’t need the money soon, you may not need to act soon.

- Rebalance if it’s part of the plan (and only if you can stick with it).

- Reduce inputs that amplify panic (constant checking, rage headlines, “doom influencer” accounts).

Specific Examples: How Cycles “Rhymed” Without Repeating

The details of each market episode are unique, but the pattern of emotions and re-pricing shows up again and again.

The tech boom and bust (late 1990s into the early 2000s)

A powerful story (“the internet changes everything”) was true in a broad sense, but markets often overpay for true things. When valuations get stretched,

the future has to be perfect for prices to make sense. When reality is merely “pretty good,” expectations resetsometimes violently.

The global financial crisis (2007–2009)

Leverage and fragile funding structures turned a housing downturn into a system-wide stress test. The lesson wasn’t “never own stocks.” It was:

understand risk, avoid concentrated bets you can’t endure, and recognize that credit cycles matter.

The pandemic shock and recovery (2020 and after)

Fast drops can be followed by fast rebounds. Many investors who sold during panic missed the recovery because the market tends to move ahead of the news.

Cycles can turn before the headlines feel safe.

The inflation-and-rates era (early 2020s)

When inflation rises and rates move up, leadership can shift. What worked under low rates may struggle under higher rates, and diversification suddenly looks

less like “boring” and more like “useful.”

The big takeaway across eras: you don’t have to predict the next cycle to benefit from it. You have to avoid self-sabotage inside it.

The Dependability of Cycles Is Actually Good News

“Cycles happen” sounds scary until you realize the alternative is worse. If markets never had downturns, they also wouldn’t offer meaningful long-term

rewards. Risk and cycles are the admission price.

The dependable part is not the scheduleit’s the existence of change. And once you accept that, you can design a plan that doesn’t require you to

be right all the time. Just consistent.

Experiences Related to the Dependability of Cycles (Real-World Patterns Investors Live Through)

The concept of cycles lands differently when it’s not a chartit’s your actual money. Below are common experiences investors report living through across

bull and bear markets. These aren’t meant to be dramatic morality plays; they’re everyday examples of how cycles feel from the inside.

Experience #1: “I checked my account and became a philosopher.”

In a rising market, investors often feel calm, rational, and oddly qualified to give financial advice at barbecues. Then a drawdown arrives and the same

people suddenly discover stoicism, minimalism, and the emotional range of a shaken soda can. The cycle doesn’t just change pricesit changes how confident

we feel about our own decisions. Many investors learn the hard way that an aggressive portfolio is only “appropriate” until it stops going up.

Experience #2: The performance-chasing loop

A classic cycle goes like this: an investor notices a fund or sector that has crushed it for two or three years. Friends are talking about it. Social

media is full of victory laps. The investor buys near the moment the story becomes mainstreamright as expectations peak. Then leadership rotates, returns

cool off, and frustration sets in. They sell… and later repeat the process with the next hot thing. This is how cycles turn normal volatility into personal

underperformance: buying late, selling early, and paying an “emotion tax” along the way.

Experience #3: The rebalancer who felt silly (until they didn’t)

Some investors rebalance on schedule. In good times, that means trimming winners, which feels like leaving money on the table. In bad times, it means

adding to losers, which feels like throwing good money after bad. The emotional experience is mostly discomfortright up until the cycle turns and the

disciplined behavior starts looking wise. Rebalancing won’t win every year, but many investors find it helps them stay aligned with their risk level and

prevents the portfolio from turning into a concentrated bet without their permission.

Experience #4: The “cash forever” friend

Every cycle creates at least one person who vows never to invest again. After a scary downturn, holding cash feels safe and virtuouslike wearing a helmet

indoors. The problem is that markets can recover while fear lingers. If someone stays in cash waiting for “certainty,” they may miss a meaningful portion

of the rebound. Over time, the cycle teaches a subtle lesson: the feeling of safety can be expensive if it keeps you from participating in long-term

growth.

Experience #5: The steady contributor who “accidentally” did it right

Not everyone needs a sophisticated strategy. Many long-term investors do well simply by contributing regularly to diversified investments, keeping costs

reasonable, and not changing plans every time the world gets loud. During downturns, they keep buying because the contributions are automatic. In bull

markets, they keep buying because the habit is intact. It doesn’t look heroic in the moment, but across cycles it can be powerful: the plan keeps working

while emotions cycle in and out.

Experience #6: The business owner’s cycle lesson

Investors who also run businesses often recognize cycles fasternot because they predict markets, but because they feel real-world demand, hiring changes,

and financing conditions. In good times, expansion feels natural. In tighter times, preserving cash and flexibility becomes the focus. This experience can

translate well into investing: you don’t need to “win” every quarter. You need to stay solvent, stay flexible, and be positioned to take advantage of the

next upswing when it arrives.

These experiences share a common theme: cycles are inevitable, but outcomes vary based on behavior. The most durable advantage isn’t forecasting; it’s

having a plan you can follow when you least feel like following it.