Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why TD Care Shouldn’t Be a One-Person Show

- Occupational Therapy for TD: Independence, Adaptation, and “Life Logistics”

- Physical Therapy for TD: Balance, Mobility, and Keeping You Steady

- Speech Therapy for TD: Clear Communication and Safe Swallowing

- How Therapists Complement Medical Treatment (Including VMAT2 Inhibitors)

- What a Collaborative TD Care Team Looks Like

- When to Ask for OT, PT, or Speech Therapy Referrals

- How to Get the Most Out of Therapy: Practical Tips

- Common Myths About Therapy in TD (Let’s Retire Them)

- Conclusion: Add the People Who Help You Live, Not Just Treat Symptoms

- Experiences Related to Adding OT, PT, and SLP to a TD Care Team (Extended)

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) can feel like your body is running background apps you never downloadedextra movements that pop up during conversations, meals, walks, or the exact moment you’re trying to look “totally normal” in a serious meeting. While TD is often linked to certain medications (most commonly dopamine-receptor blocking drugs like many antipsychotics, and sometimes medicines used for nausea), the day-to-day impact is rarely “just movements.” It’s function. It’s confidence. It’s safety. It’s getting through a regular Tuesday without turning every task into a mini obstacle course.

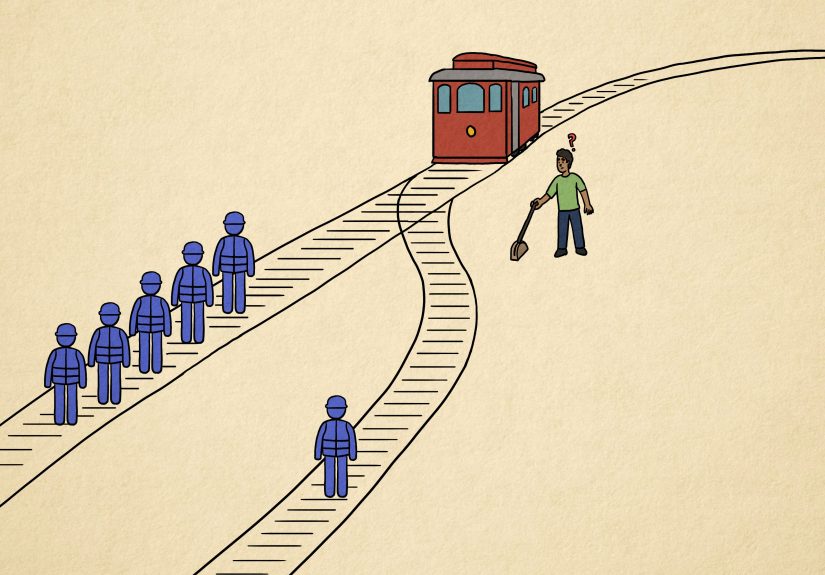

That’s why a strong TD care plan often works best as a team sport. Your prescribing clinician (often a psychiatrist or neurologist) may address medication strategylike adjusting doses, switching meds when appropriate, or considering FDA-approved treatments that can reduce TD symptoms. But symptom reduction isn’t the same as rebuilding daily life. This is where occupational therapists (OTs), physical therapists (PTs), and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) become your practical, real-world MVPs.

In this article, we’ll break down what each therapy discipline does, how they fit into a comprehensive tardive dyskinesia care team, and what you can expect from therapywithout the confusing jargon and with a few gentle jokes that won’t interfere with your treatment plan.

Why TD Care Shouldn’t Be a One-Person Show

TD can involve repetitive, involuntary movementsoften in the face, mouth, and tongue, but sometimes in the trunk and limbs too. That can affect eating, speaking, writing, typing, walking, balance, posture, and even how comfortable you feel in public. And because TD symptoms can fluctuate with stress, fatigue, or distractions, you might have “good hours” and “why is my body doing jazz hands?” hours.

A prescribing clinician is essential for diagnosis, monitoring, and medical treatment decisions. But rehabilitation therapists specialize in something that matters just as much: how you function in real life. They don’t just ask, “What are the movements doing?” They ask:

- How are these movements affecting meals, hygiene, and getting dressed?

- Are you avoiding social situations because speaking feels harder?

- Are you at risk for falls, pain, or fatigue from compensating?

- What can we change at home, at work, and in routines so your life fits you again?

That shiftfrom symptoms to functionis exactly why OT, PT, and SLP belong on many TD care teams.

Occupational Therapy for TD: Independence, Adaptation, and “Life Logistics”

Occupational therapy is about helping you do the daily activities (“occupations”) that make up your life: getting ready in the morning, cooking, working, using a phone, managing medications, and participating in hobbies and relationships. In TD, involuntary movements can make fine-motor tasks unpredictable. OTs help you regain control through strategy, adaptation, and environment design.

What an OT can do for tardive dyskinesia

- Daily living skill support: easier ways to button shirts, apply makeup, shave, brush teeth, or handle contact lenses when movements interrupt precision.

- Eating and meal tools: adaptive utensils, cups, plates, and set-ups that reduce spills, improve grip, and lower frustration. (Yes, there are forks designed for shaky daysand they’re not cheating. They’re engineering.)

- Writing and typing adaptations: grips, pens, keyboard set-ups, voice-to-text workflows, and pacing strategies to reduce fatigue and improve accuracy.

- Home and workplace modifications: reorganizing frequently used items, stabilizing work surfaces, reducing clutter, improving lighting, and setting up a “low-friction” environment.

- Energy conservation and pacing: planning tasks so you’re not doing everything when symptoms are loudestbecause “powering through” is not a long-term strategy.

- Routine building: medication management routines, reminders, and habit supportsespecially important when you’re balancing mental health treatment with movement symptoms.

Real-world OT example

Imagine TD-related mouth and hand movements make meals stressful. An OT might recommend a stable plate with a raised edge, a weighted or built-up handle utensil, and a table set-up that reduces sliding. They may also coach you on pacing (smaller bites, fewer distractions, planned breaks) so you can eat with less tension and fewer accidents. It’s not about perfectionit’s about easier.

Physical Therapy for TD: Balance, Mobility, and Keeping You Steady

Physical therapy focuses on movement quality, mobility, strength, balance, endurance, posture, and safety. If TD affects your trunk or limbsor if you’ve developed compensatory patterns to “fight” unwanted movementsPT can help reduce fall risk, improve walking confidence, and protect joints and muscles from overuse.

What a PT can do for tardive dyskinesia

- Gait (walking) assessment and training: improving step timing, stability, and turningareas where involuntary movements can throw off rhythm.

- Balance and fall-prevention: targeted balance drills, reactive stepping practice, and strategies for navigating curbs, stairs, and crowded spaces.

- Strength and endurance: building foundational strength so your body is less vulnerable to fatigue, which can worsen movement control.

- Posture and alignment: improving positioning and reducing strainespecially if you’re bracing or tensing to “hold still.”

- Flexibility and mobility: stretching and range-of-motion work that protects comfort and function.

- Assistive devices when needed: selecting and training with a cane or walker only if it truly helpsnot as a default.

Real-world PT example

Someone with TD may feel unsteady during quick direction changes in grocery aisles (the natural habitat of sudden turns and surprise children). A PT can work on turning strategies, controlled stops, safe reaching, and practice with real-life scenarios. It’s like rehearsal for the worldminus the awkward applause at the end.

Speech Therapy for TD: Clear Communication and Safe Swallowing

Speech-language pathologists (SLPs) help with communication (speech clarity, voice, and intelligibility) and swallowing (dysphagia). TD frequently involves the face, mouth, tongue, and jawexactly the equipment used for talking and eating. When TD affects these areas, speech can become less clear, saliva control can be challenging, and swallowing safety may be affected.

What an SLP can do for tardive dyskinesia

- Speech clarity strategies: pacing, over-articulation techniques, breath support, and communication “repair” strategies (how to repeat or rephrase without feeling defeated).

- Swallowing screening and evaluation: identifying signs of swallowing difficulty and recommending next stepssometimes including instrumental assessments when appropriate.

- Safe swallowing strategies: positioning, timing, bite/sip modifications, texture guidance, and strategies to reduce coughing or choking risk.

- Saliva management and oral-motor coordination: practical techniques to improve comfort and confidence in social settings.

- Alternative/augmentative communication (AAC) when needed: not as a “last resort,” but as a toollike using GPS instead of insisting you can navigate solely by vibes.

Why swallowing support matters

Swallowing issues can raise risks like dehydration, poor nutrition, and aspiration (food/liquid going “the wrong way”), which can lead to serious complications. If you notice frequent coughing with meals, throat clearing, a “wet” voice after drinking, or avoiding certain textures, an SLP can help you get clarity and a safer plan.

How Therapists Complement Medical Treatment (Including VMAT2 Inhibitors)

Medical treatment and therapy aren’t competing storylines. They’re parallel tracks that intersect for better outcomes. Some people with TD may be candidates for FDA-approved medications that can reduce involuntary movements (your clinician will decide what’s appropriate based on your medical history and overall treatment goals). Even when symptoms improve with medication, therapy helps with:

- Rebuilding skills you’ve avoided (like eating in public or speaking up in meetings).

- Reducing compensations that cause pain or fatigue (like tensing shoulders all day).

- Preventing secondary problems such as falls, musculoskeletal strain, or social withdrawal.

- Translating symptom changes into real functionthe part that matters at 7:12 a.m. when you’re trying to get out the door.

Think of it this way: medication may turn down the volume, while therapy teaches you how to live well with the soundtrackwhether it’s loud today or not.

What a Collaborative TD Care Team Looks Like

A strong tardive dyskinesia care team often includes:

- Prescribing clinician (psychiatrist, neurologist, or other qualified prescriber): diagnosis, monitoring, medication strategy.

- Primary care clinician: overall health, coordination, managing comorbidities.

- Pharmacist: medication review, interactions, adherence support, side effect education.

- OT / PT / SLP: function-focused assessment and interventions tailored to your daily life.

- Mental health therapist / counselor (often helpful): coping strategies, anxiety and stigma support, confidence rebuilding.

The best teams communicate. That might mean shared notes, coordinated goals, or simply making sure everyone is working toward what you care about: “I want to eat without embarrassment,” “I want to feel steady walking outside,” “I want to speak clearly on calls,” or “I want to stop avoiding my friends.”

When to Ask for OT, PT, or Speech Therapy Referrals

You don’t have to wait until things feel extreme. Consider asking for therapy if you notice any of the following:

OT referral signals

- Difficulty eating, grooming, dressing, writing, typing, or managing daily routines.

- Increased spills, dropped items, frustration with fine-motor tasks.

- Avoiding hobbies or tasks you used to enjoy because they’ve become exhausting.

PT referral signals

- Feeling unsteady, fearful of falling, or “off-balance,” especially on stairs or uneven ground.

- New aches and pains from tensing or compensating.

- Reduced activity because movement feels unpredictable.

SLP referral signals

- Speech feels less clear, you repeat yourself often, or you avoid talking in groups.

- Coughing/choking with meals, frequent throat clearing, or avoiding certain foods/liquids.

- Drooling or saliva control issues that affect comfort and confidence.

How to Get the Most Out of Therapy: Practical Tips

Therapy works best when it’s specific, functional, and realistic. A few ways to speed up progress:

- Bring examples: a short symptom log, a list of “hard tasks,” or even a video of movements (if you’re comfortable) can help therapists tailor strategies.

- Set goals that matter: “eat soup without wearing it,” “walk to the mailbox confidently,” “present in a meeting without avoiding words.”

- Ask for carryover plans: home exercises, cue cards, environmental changesthings you can actually maintain.

- Include caregivers when appropriate: training a partner or family member can reduce stress and improve consistency.

And a gentle reminder: therapy is not a reality show. You don’t have to “win” each session. You just have to learn what helps you.

Common Myths About Therapy in TD (Let’s Retire Them)

Myth 1: “Therapy can’t help because TD is neurological.”

Therapy may not “cure” TD, but it can meaningfully improve safety, independence, communication, swallowing function, and quality of life. That’s not a consolation prizethat’s the point.

Myth 2: “If medication helps, I don’t need therapy.”

Medication can reduce movements, but therapy helps you rebuild skills, confidence, and routinesespecially if you’ve been avoiding tasks or developed compensations.

Myth 3: “Speech therapy is only for strokes.”

SLPs work with many conditions affecting speech and swallowing, including movement disorders. If TD is impacting your mouth, tongue, jaw, or coordination, an SLP can be highly relevant.

Conclusion: Add the People Who Help You Live, Not Just Treat Symptoms

Tardive dyskinesia care is more than managing movementsit’s restoring your ability to function and feel like yourself in the spaces that matter: meals, conversations, work, and daily routines. Occupational therapists help you adapt tasks and environments. Physical therapists help you move safely and confidently. Speech-language pathologists help protect swallowing, improve communication, and reduce the stress that comes from feeling misunderstood.

If your TD plan currently feels like it’s missing the “how do I actually live with this?” chapter, OT, PT, and SLP may be the missing authors. And you deserve a care team that treats your whole life, not just your symptom list.

Experiences Related to Adding OT, PT, and SLP to a TD Care Team (Extended)

People often describe the early stage of TD as confusingnot only because the movements can feel sudden or unpredictable, but because the impact sneaks into everyday moments. One person might notice lip or tongue movements show up during stressful conversations, then start avoiding phone calls. Another may realize eating has become a “two-napkin minimum” event, so they quietly stop going out to restaurants. And someone else might feel unsteady while walking, then gradually shrink their world to “safe routes” inside the home. These experiences don’t always show up in a quick medical appointment, which is why therapy can feel like the first time someone addresses the whole problem.

Many people report that occupational therapy feels immediately practical. Instead of general advice, OTs often start by asking what’s hardest this week. For example, someone who loved cooking might feel frustrated because chopping and stirring are suddenly unpredictable. An OT might suggest stabilizing the cutting board, switching to safer knives or tools, changing the order of steps, or prepping ingredients at times of day when symptoms are calmer. People often say this kind of “small engineering” reduces stressand when stress drops, symptoms can feel more manageable too. The win isn’t just fewer spills; it’s the return of confidence and routine.

Physical therapy experiences commonly center on safety and freedom. Some people with TD describe feeling “wobbly,” especially when turning quickly, stepping off curbs, or carrying groceries. PT sessions may focus on balance reactions, controlled turns, strengthening, and practicing real-life tasks. A recurring theme people mention is relief: once they learn strategies for stability and build strength, they stop second-guessing every step. It’s not about becoming an athlete overnight; it’s about walking to the mailbox without negotiating with gravity like it’s a stubborn landlord.

Speech therapy experiences can be especially powerful because communication and swallowing are deeply social. People often say they didn’t realize how much energy they were spending on “passing as normal” until an SLP offered practical toolslike pacing strategies, clearer articulation techniques, or ways to handle moments when words come out messier than intended. When swallowing is involved, many people describe a shift from fear to control: learning safer strategies, understanding textures, and knowing when a more detailed evaluation is needed can reduce anxiety at meals. For some, the biggest change is socialbeing able to eat with family again without constant worry or embarrassment.

Across OT, PT, and SLP, a common experience is that therapy turns TD from a vague, overwhelming problem into a set of workable challenges. People often describe feeling less alone because therapists normalize the struggle, teach skills, and break goals into steps. Instead of “my body is doing something scary,” it becomes “here’s what helps on a rough day, here’s what supports me long-term, and here’s how my team and I track progress.” Even when symptoms don’t disappear, quality of life can improve in ways that matter: more independence, safer movement, clearer communication, and fewer moments where TD gets to be the loudest voice in the room.