Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Sy Berger matters (even if you’ve never heard his name)

- The 1952 Topps set: the moment cardboard became a calendar

- From gum to global: how Topps turned a hobby into a habit

- The Mickey Mantle effect: when “trash” becomes treasure

- Baseball cards as American culture on paper

- How the modern market works: grading, scarcity, and storytelling

- The Berger blueprint in the Fanatics era

- What Sy Berger really changed

- Field Notes: of real-life experiences baseball cards tend to create

Baseball cards have a funny way of sneaking into your life. One minute you’re a kid with sticky fingers and a pack of gum,

the next you’re an adult explainingvery calmly, very rationallywhy a rectangle of cardboard deserves its own insurance policy.

Somewhere between those two realities stands one quietly influential figure: Sy Berger, the Topps executive often credited with

shaping the modern baseball card as we know it.

Berger didn’t invent baseball. He didn’t invent photography. He didn’t even invent the idea of putting athletes on small paper collectibles.

What he did inventthrough taste, persistence, and a surprisingly practical understanding of how kids (and later, adults with disposable income)

pay attentionwas the modern blueprint for baseball cards: bold color, readable player bios, stats on the back, and a standardized “set” concept

that turned casual purchases into a mission.

If that sounds small, consider the ripple effects. Baseball cards helped sell the sport to new fans, taught generations to read box-score stats,

built communities in neighborhoods and card shops, and eventually helped create a collectibles economy big enough to make headlines when a single card

sells for eight figures. That’s not just nostalgia. That’s cultural infrastructurewrapped in wax paper.

Why Sy Berger matters (even if you’ve never heard his name)

Sy Berger worked for Topps in an era when trading cards were shifting from tobacco pack inserts and regional novelties into mass-market entertainment.

In the early 1950s, Topps wanted to competeand winby making its baseball cards more visually exciting and more “complete” as a product experience.

Berger became the person tasked with making that happen.

He didn’t approach baseball cards like museum objects. He approached them like something a kid would beg for at the corner store.

Which meant the cards needed to be bright, consistent, and loaded with just enough information to feel like you owned a tiny piece of the big leagues.

In other words: the card had to be a portable fan identity.

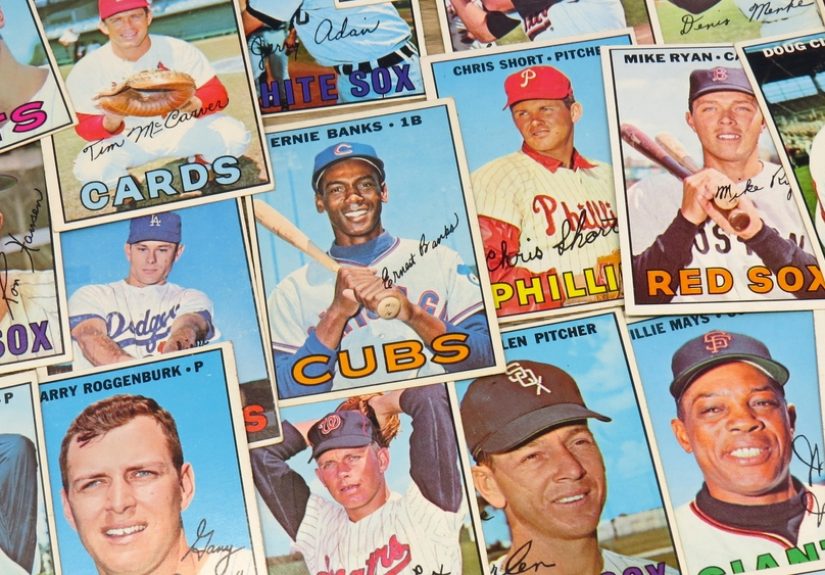

The 1952 Topps set: the moment cardboard became a calendar

The 1952 Topps baseball set is widely treated as a landmarkpartly because it looks like the ancestor of almost every mainstream baseball card design

that followed. Bigger format. Color portraits. A clean nameplate. And, crucially, player information and statistics on the back that made each card

feel like a miniature media page.

The “set” idea mattered as much as the design. A set creates a storyline: you’re not just buying a card, you’re building a roster,

assembling a league, completing a universe. That turns random purchases into a questone that can last all summer, all childhood,

or, if you’re really committed, all adulthood.

Stats on the back: the hidden revolution

It’s easy to overlook the back of a baseball card until you remember what it did for kids who couldn’t watch every game.

A card back turned baseball into something you could study. Hits, home runs, ERAnumbers that gave fans a way to argue (politely or not)

about who was actually great, not just famous.

Berger and Topps leaned into that “baseball as data” idea early, pulling from official league publications to populate the backs.

The result was a generation of fans raised on stats long before analytics became a mainstream talking point.

If you’ve ever heard someone debate a player using numbers like they’re reciting poetry, you’ve seen the legacy.

From gum to global: how Topps turned a hobby into a habit

Topps didn’t just sell cards. It sold a ritual: crack the pack, smell the gum, sort the cards, trade doubles, protect favorites,

and dream about the one you still needed. That ritual scaled because it was simple and repeatable. And because it was social.

Baseball cards became a kid-friendly economy. Cards were currency on the school bus. A star player could “cost” three commons.

A rookie with hype could be priceless for exactly one week (which, in kid-time, is basically a fiscal quarter).

That trading culture built negotiation skills, social bonds, and a shared languagelong before social media gave everyone a feed.

Mass availability created mass memory

There’s a reason baseball cards feel like a time machine. They were printed in huge quantities, distributed everywhere,

and handled constantly. That made them one of the most democratic forms of sports memorabilia: you didn’t need to travel to a stadium

or buy a ticket to hold a piece of baseball culture. You just needed a few coins and the patience to open packs without bending corners.

The Mickey Mantle effect: when “trash” becomes treasure

No discussion of Berger-era Topps can avoid the gravitational pull of the 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle card.

It’s not just iconicit’s become a symbol of what the entire hobby can represent: rarity, condition, mythology, and the emotional charge

of childhood objects surviving into adult value.

In August 2022, a high-grade example of the 1952 Topps Mantle sold for $12.6 million, a record-level price that signaled how serious

the high end of the sports collectibles market had become. That sale didn’t happen because Mantle was merely a great player.

It happened because the card sits at the intersection of history, scarcity, and cultural obsession.

The ocean story (yes, really)

One of the hobby’s most legendary tales is also one of its most on-brand: unsold inventory.

The story goes that Topps had leftover 1952 stock taking up space, and rather than keep warehousing it forever,

cases were dumped into the Atlantic. Whether you focus on the logistics or the symbolism, the lesson is the same:

value is not baked init’s made over time, by culture and demand.

In a way, that story is the perfect metaphor for collecting. The things we ignore today can become tomorrow’s artifacts.

Also, it’s a comforting reminder that even major companies sometimes solve problems with the business equivalent of

“well… we could throw it in the ocean.” (Please don’t do this with your unsold merch. The ocean has enough going on.)

Baseball cards as American culture on paper

Baseball cards did more than mirror the sport; they helped spread it. Long before streaming, highlight clips, and endless podcasts,

cards were a portable media channel. They carried player faces into homes that might never see a live game in person.

For decades, they functioned as advertising, storytelling, and fandom training wheels all at once.

They also became accidental archives. Card sets record uniforms, team names, stadium references, and shifting graphic styles.

They preserve the “normal” players toothe middle relievers and bench guys who rarely get a documentary but still lived the game.

Collect a full set from a season and you’re holding a democratic snapshot of baseball’s ecosystem.

A quick nod to the other “fathers” of the hobby

Berger helped define the modern, mass-market baseball card. But the hobby also owes a debt to collectors and cataloguers

who gave the chaos a structure. Jefferson Burdick, for example, created classification systems that still shape how vintage sets are discussed

(the famous “T206” designation traces back to his cataloging work). Without that kind of organization, collecting would be a lot closer to

“a pile of stuff” than a documented cultural practice.

How the modern market works: grading, scarcity, and storytelling

If you’ve been away from the hobby for a while, here’s the modern twist: condition is king, and grading companies act like referees.

Third-party grading assigns a numerical score to a card’s condition and seals it in a protective holder. That single step can transform

a card from “cool find” into “auction headline,” because it reduces uncertainty for buyers.

The scale of grading today is enormous, reflecting how collecting has become both a hobby and a marketplace.

Over the last few years, millions of cards have been authenticated and graded annually, and the volume has become a key indicator of market activity.

In other words: the hobby isn’t just aliveit’s industrial.

New kinds of rarity: the 1-of-1 era

Vintage scarcity often comes from survival: fewer copies remain in great condition, and some were lost to time, moves, basements, bike spokes,

and parents who cleaned bedrooms with the efficiency of a small tornado.

Modern scarcity is frequently manufactured on purpose. Today’s products include serial-numbered parallels, autograph cards,

and “1-of-1” inserts designed to be unique by definition. When a modern 1-of-1 rookie card sells for seven figures,

it’s not only about the player. It’s about the story: the pull, the moment, the provenance, the social buzz.

The product is engineered for narrativebecause collectors don’t just buy cardboard; they buy meaning.

The Berger blueprint in the Fanatics era

The business side of baseball cards keeps evolving. In 2022, Fanatics completed its acquisition of Topps’ trading cards and collectibles business,

a deal that reshaped how licensing, production, and distribution might look in the years ahead.

Even in a new corporate chapter, the fundamentals that Berger championed still matter: design clarity, set-building appeal,

and the emotional jolt of opening a pack.

Think of Berger’s influence as a product philosophy. A baseball card should be easy to recognize, fun to collect, and informative enough

to make a player feel real. That philosophy can live on in glossy chrome, in digital companion apps, or in whatever comes nextbecause it’s not

tied to a printing press. It’s tied to human behavior.

What Sy Berger really changed

Berger didn’t just help Topps win a market. He helped baseball cards become a shared cultural toola way fans could carry the sport in a pocket,

build friendships through trading, and learn the game through statistics. He helped turn collecting into a structured experience:

the chase, the set, the story.

And that structure did something bigger than create nostalgia. It created continuity. Baseball changes slowly, but it still changes:

teams move, ballparks disappear, styles shift, legends fade. Cards keep receipts. They remind people what a season looked like,

who mattered, and what “the game” felt like at the time.

That’s why it’s fair to say Sy Berger changed the world with baseball cardsbecause he helped change how people remember.

And memory, once you scale it, is culture.

Field Notes: of real-life experiences baseball cards tend to create

Baseball cards aren’t just collectibles; they’re little life events. Ask ten collectors how they got started and you’ll hear

ten versions of the same plot twist: “I didn’t mean to get serious.” It begins innocentlyone pack, one favorite player, one trade.

Then you learn the first unwritten rule of the hobby: if you say, “I’m just buying one pack,” the universe hears, “I would like a lifelong obsession.”

One of the most common experiences is the “shoebox era.” Many people have a boxsometimes literal, sometimes metaphoricalwhere childhood cards lived

through moves, school changes, and the awkward phase where you decided sports were “uncool” (a decision history has not forgiven).

Years later, you open that box and the smell hits first: cardboard, old paper, maybe a hint of attic. The memories arrive like a highlight reel.

You can practically hear the bike tires on pavement and the sound of someone yelling, “No tradesthis one’s staying with me.”

Another classic experience is the card shop education. The first time you walk into a real hobby shop, it can feel like entering a tiny stock exchange

where everyone speaks in player names, set years, and grading numbers. You learn quickly that condition matters, sleeves are not optional,

and that there are two types of collectors: the ones who say they don’t care about centering, and the ones who are lying to themselves.

You also discover something surprisingly wholesome: shops are social hubs. People talk across generationskids with new pulls,

adults chasing childhood favorites, and veteran collectors who seem to know the population report like it’s their favorite bedtime story.

Card shows create their own kind of memory. You’ll see display cases with vintage legends, bargain bins full of “maybe someday” rookies,

and tables where someone is proudly selling the exact player you couldn’t stand as a kid. You learn how to negotiate politely,

how to walk away when the price is wrong, and how to circle back like a diplomat when you change your mind.

You also learn the emotional math of collecting: the card you buy isn’t always the one with the highest valueit’s often the one that

completes a personal story.

And then there’s the experience that ties directly back to Sy Berger’s influence: the back of the card.

Plenty of collectors remember reading card backs like mini textbookslearning which hand a player batted with, where he was born,

what year he debuted, and how his stats climbed or crashed. For some people, that’s where fandom became understanding.

Not just “I like this player,” but “I know why he matters.” Berger’s card format didn’t merely entertain; it taught.

Ultimately, the most “real” experience in the hobby is connection. Cards connect you to a sport, to a time period, and to other people.

You trade stories as much as you trade cardboard. That’s the quiet magic: a small object that keeps opening big conversations

generation after generation.