Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Before Ludlow: Life in the Coal Camps Was a “Company Town” Starter Kit

- The 1913–1914 Strike: What the Miners Wanted (Spoiler: Not a Yacht)

- Why the Rockefellers Got Blamed

- April 20, 1914: The Day Ludlow Burned

- Aftermath: The Ten-Day War and a Nation That Couldn’t “Unsee” It

- Rockefeller’s Countermove: The Birth of Corporate “Crisis PR”

- What Ludlow Changed (and What It Didn’t)

- So, Was Ludlow “Unleashed” by the Rockefellers?

- Experiences: How People Connect With Ludlow Today (and Why It Still Hits Hard)

- Conclusion

In April 1914, a patch of prairie near Ludlow, Colorado became a national scandalone that still reads like a warning label on unchecked corporate power.

What began as a labor strike over dangerous working conditions, punishing pay systems, and company-town control ended with a tent colony in flames, families dead,

and the word “Ludlow” turning into shorthand for industrial brutality.

The headline version is blunt: state troops and company-aligned forces attacked striking coal miners and their families; the camp burned; women and children died.

The deeper story is messierand more important. It’s a story about who gets to define “law and order,” how private wealth can bend public institutions,

and what happens when workers demand basic dignity in a system designed to keep them quiet, hungry, and replaceable.

And yes, the Rockefellers are in the middle of it. Not as battlefield commanders holding a match, but as the powerful owners whose company policies,

anti-union posture, and political influence helped build the conditions where a massacre became possibleand where many Americans decided the family should be held

responsible for the outcome.

Before Ludlow: Life in the Coal Camps Was a “Company Town” Starter Kit

Southern Colorado’s coal country in the early 1900s was the kind of place where the company didn’t just employ youit surrounded you.

Many miners lived in company-owned housing, bought food at company stores, and navigated a workplace where safety rules were often treated as optional

(unless breaking them saved money).

The pay system sounded straightforwardpaid by the tonbut reality had sharp edges. In some operations, coal could be weighed by standards that benefited the company

(a “ton” could mysteriously feel heavier when payday arrived). Workers also fought over “dead work”: essential labor like timbering, laying track, clearing hazards,

and wetting coal dusttasks that made mines safer but often weren’t compensated like actual coal production.

Add in long hours, a constant threat of roof falls, gas, explosions, and the everyday power imbalance of armed guards and blacklists, and you have a workplace where

“quit if you don’t like it” wasn’t a real optionbecause quitting could mean losing your home, your credit, and your future jobs in the region.

The 1913–1914 Strike: What the Miners Wanted (Spoiler: Not a Yacht)

In September 1913, thousands of miners organized with the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) and went on strike across southern Colorado.

Their demands were not exotic. They wanted enforcement of existing labor laws (including the eight-hour day), the right to choose their own doctors and stores,

fairer systems for weighing coal, pay for “dead work,” improved safety enforcement, andmost controversiallyrecognition of the union as a bargaining agent.

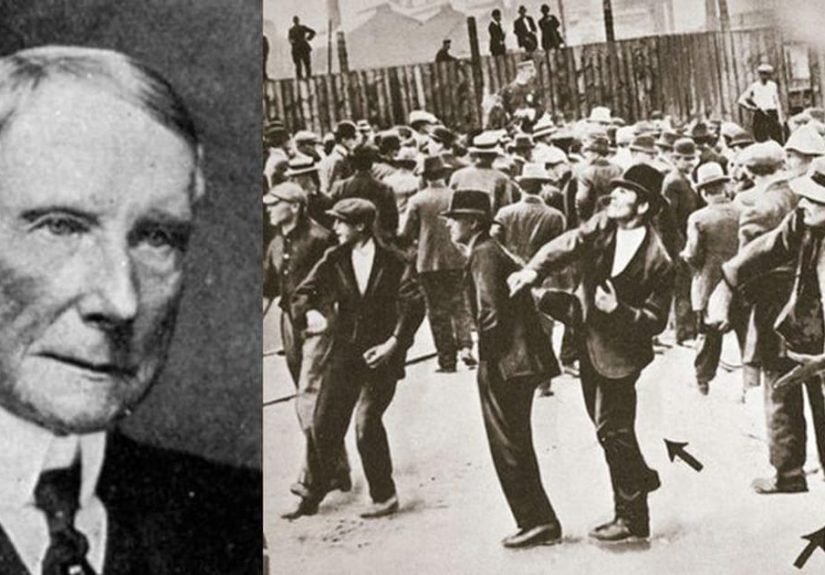

The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company (CF&I) was a major target, and its ownership structure mattered. John D. Rockefeller Jr. was widely viewed as the dominant

shareholder behind CF&Ione reason public anger would later focus on him personally, even though he was far from Colorado when bullets started flying.

In the logic of the era (and honestly, the logic of now), controlling ownership meant responsibility: if you benefit from a system, you don’t get to act shocked

when that system injures people.

Evictions: The Moment the Strike Turned Into a Humanitarian Crisis

When miners struck, many were evicted from company housing. The union helped set up tent colonies on open landLudlow became the largest, housing roughly a thousand

people at times. The camps were not a camping trip with s’mores and scenic vibes. They were families trying to survive Colorado weather in canvas tents while

armed conflict escalated around them.

Violence wasn’t a side effectit was part of the strategy. Mine operators hired private guards; strikers armed themselves; intimidation and shootings became

grimly routine. One notorious detail that shows up in multiple accounts: an armored vehicle nicknamed the “Death Special,” used to fire into tent colonies

and terrorize families at night. If you think modern labor disputes get spicy on social media, Ludlow was “machine-gun spicy.”

Why the Rockefellers Got Blamed

To understand why “Rockefeller” became glued to the Ludlow story, picture the power map. CF&I was a huge employer. The state relied on coal.

The company relied on political relationships, private security, and a hard “open shop” (anti-union) stance. Rockefeller Jr., as the face of ownership,

defended the company’s position publicly and was seen by critics as endorsing a fight “at any cost.”

Did he personally order an attack on the Ludlow tent colony? There’s no credible evidence that he issued battlefield instructions like a general.

But did his company’s leadership and policiessupported by his money and authorityhelp create the conditions for catastrophe? That’s the argument that exploded

nationwide after the massacre, and it’s why protestors treated Rockefeller as the symbolic author of what happened.

April 20, 1914: The Day Ludlow Burned

On the morning of April 20, Colorado National Guard troops and company-aligned forces confronted the Ludlow tent colony.

Accounts differ about which side fired first, but what followed was a long firefight that pinned families inside a camp made of canvas, wood, and fear.

Machine-gun positions on higher ground turned the colony into a shooting gallery.

As the battle dragged on, women and children hid wherever they couldsome in a dry arroyo, some in wells or nearby structures,

and some in pits dug beneath the tents for exactly this nightmare scenario.

The “Death Pit”: A Detail So Horrifying It Became a Rallying Cry

The most infamous tragedy at Ludlow happened beneath one tent: a cellar-like pit where women and children sheltered from gunfire.

When the tent colony was set on fire, the pit became a trap. In widely reported accounts, 11 children and two women died thereburned and suffocated,

hidden from sight until the next day’s search turned horror into undeniable fact.

The camp was destroyed. A strike leader, Louis Tikas, was killed during the violence (and accounts of his death fueled accusations of abuse and execution-style

brutality). The casualties at Ludlow are often described as around 20–21 dead, with the women-and-children deaths at the center of the nation’s outrage.

The exact totals vary by source and definition, but the moral math is simpler: families died in a labor conflict where they never should have been targets.

Aftermath: The Ten-Day War and a Nation That Couldn’t “Unsee” It

Ludlow didn’t end the strikeit detonated it. In the days that followed, armed miners attacked company installations and clashed with forces across

southern Colorado in what became known as the Ten-Day War, part of the broader Colorado Coalfield War.

The violence expanded until the federal government intervened; President Woodrow Wilson ordered federal troops to restore order and disarm the region.

The strike ultimately failed to win union recognition in the short term. Many miners lost jobs; the union ran out of money; the strike ended later in 1914.

Meanwhile, accountability was… let’s call it “selective.” Court-martials and investigations occurred, but meaningful punishment for those responsible was rare,

and public confidence in “justice” was not exactly boosted by the outcome.

Rockefeller’s Countermove: The Birth of Corporate “Crisis PR”

If Ludlow exposed the violence of industrial conflict, it also helped shape something else: modern corporate reputation management.

The Rockefellers faced protests and national condemnation. The response wasn’t just legalit was public relations.

Rockefeller Jr. hired professional image and labor-relations help, including publicist Ivy Lee (a pioneer of crisis communications) and advisers who pushed

a new approach: improve conditions, talk about harmony, build worker representation plans, and present the company as a responsible partner rather than

a coercive ruler. CF&I’s later “employee representation” approach became a model other companies watched closelysometimes praised as reform,

sometimes criticized as paternalism designed to blunt independent union power.

In plain terms: Ludlow forced powerful people to learn that “no comment” doesn’t work when the country sees dead children in the news.

They needed a story. They needed photographs. They needed a tour. They needed a plan that looked like progress.

What Ludlow Changed (and What It Didn’t)

Ludlow didn’t immediately transform labor conditions in Colorado. But it became a landmark event in American labor historycited in debates about mine safety,

child labor, working hours, and the relationship between private industry and public force.

It also remains a case study in how conflict escalates when people in power treat worker demands as an invasion instead of negotiation.

Over time, the broader labor movement gained ground nationallythough not in a straight line and not because one tragedy magically fixed a system.

Ludlow’s legacy is less “the day everything changed” and more “the day everyone had to admit how bad it had gotten.”

A Place That Refuses to Disappear

The Ludlow site is remembered and preserved as a memorial landscape. A monument stands for those who died, and the story is taught, debated,

and revisited because it isn’t just about one company or one familyit’s about what any society permits when profit and authority become more important than people.

So, Was Ludlow “Unleashed” by the Rockefellers?

If by “unleashed” we mean: a Rockefeller personally gave an order to burn tentshistory doesn’t support that.

If we mean: a Rockefeller-controlled company fought unionization aggressively, relied on coercive systems, benefited from state-aligned force,

and then tried to manage the falloutthen yes, Ludlow sits in that ecosystem.

Ludlow is what happens when leadership treats workers as a problem to be contained instead of human beings to be heard.

And it’s what happens when a state’s “neutral” power isn’t neutral at all.

Experiences: How People Connect With Ludlow Today (and Why It Still Hits Hard)

You don’t have to be a labor historian to feel Ludlow in your gut. People who visit the site often describe the same unsettling contrast:

the open, quiet prairiebig sky, wind, grasspaired with the knowledge that this calm ground once sounded like gunfire and screaming.

The landscape doesn’t “look” like a battlefield in the cinematic sense. That’s part of the shock. It looks ordinary. Which is exactly the point:

extraordinary violence can happen in places that look like anywhere.

Visitors also talk about how physical memorials change the way the story lands. Reading about the “death pit” is one thing.

Standing near the marked area where families hidimagining smoke, heat, panic, and the impossible decision to either stay underground or run into gunfire

forces your brain to stop treating the massacre as an abstract paragraph and start treating it as a human event with names and ages.

Even people who arrive skeptical of “labor stories” often leave with the same thought: nobody’s kid should die because adults couldn’t negotiate a contract.

In classrooms, teachers who use Ludlow as a case study say students connect fastest through everyday details:

the idea of getting paid by a “ton” that might not be measured fairly; the insult of doing “dead work” that keeps you alive but doesn’t count as “real” labor;

the absurdity of a company providing housing, stores, and rulesthen calling that arrangement “freedom.”

Students recognize the pattern immediately, because modern versions still exist: workers tied to employers through healthcare, housing costs, gig platforms,

noncompetes (where they still appear), and the constant threat of replacement.

Descendants’ stories and community memory add another layer. In interviews and local accounts, you often hear about families who carried the trauma for decades:

grandparents who wouldn’t talk about it, or who repeated one vivid image over and over because that’s how memory works after catastrophe.

Others describe the pride side of the legacyhow organized labor, mutual aid, and immigrant communities held together under pressure,

sharing food, hiding supplies, and keeping children alive through a winter in canvas tents.

The “experience” here isn’t just grief; it’s also the stubborn, practical courage of people who refused to disappear.

For union organizers and workers today, Ludlow is sometimes treated as a grim ancestor storylike a family member everyone references when the stakes rise.

Not because anyone wants a repeat, but because it clarifies what power can do when challenged.

It also highlights something hopeful: public outrage mattered. The massacre’s visibility forced investigations, forced reforms to be discussed,

and forced elites to respond to working-class suffering in ways they had previously ignored.

If you want an “experience” without traveling, reading contemporaneous testimony and newspaper accounts can be its own form of confrontation.

The language is often shocking: people openly debating whether miners “deserved” what happened, or insisting there was “no massacre” while bodies were still being found.

That dissonancebetween reality and the official storyis eerily familiar in the modern media age. Ludlow teaches you to ask:

who benefits from the version of events that gets repeated the loudest?

Ultimately, many people walk away from Ludlow with a quieter, more personal takeaway: labor history isn’t a niche topic.

It’s the backstory of weekends, safety rules, child labor restrictions, overtime debates, and the idea that a job shouldn’t cost your life.

Ludlow is not just something that happened to “other people” in “old times.”

It’s a mirror held up to any era where workers are treated as disposableand a reminder that progress often has a price tag someone else was forced to pay.

Conclusion

The Ludlow Massacre remains one of the most infamous labor conflicts in U.S. history because it exposes something uncomfortable:

when power is concentrated and accountability is slippery, violence can become a tooleven when everyone insists they’re simply defending “order.”

The Rockefellers didn’t have to light the match personally to be linked to the fire.

Their company’s stance, influence, and refusal to treat workers as equals helped create the conditions where tragedy became likelyand where the nation

demanded someone at the top be named.

Remembering Ludlow isn’t about wallowing in horror. It’s about understanding how rights are contested, how narratives are built,

and why “work” has always been about more than wagesit’s about dignity, safety, and voice.