Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is the Trolley Problem, Really?

- The Greatest Hits: Variations That Make Your Brain Loud

- Utilitarianism vs. Deontology: The Two-Party System of Moral Philosophy

- Why Your Brain Treats a Lever Like a Remote Control, But a Push Like a Horror Movie

- Is the Trolley Problem “Realistic”? (And Why It Still Matters)

- From Tracks to Tech: Self-Driving Cars and the Modern Trolley Problem

- So… Can You Make the Impossible Choice?

- How to Discuss the Trolley Problem Without Turning Thanksgiving Into a Philosophy Cage Match

- Experiences: The Trolley Problem in Everyday Life (500+ Words)

- Conclusion: The Point Isn’t the LeverIt’s You

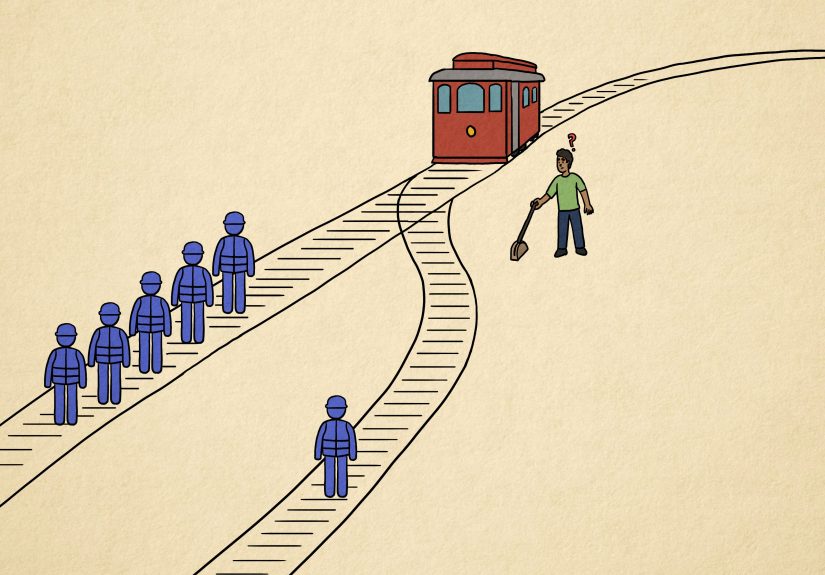

Somewhere in the universe, a runaway trolley is always having the worst day of its life. It has no brakes, terrible time-management,

and a knack for putting decent people in the role of “temporary rail-god.” You’re standing by a switch. Straight ahead: five people on the track.

On the side track: one person. Pull the lever or don’t. That’s it. That’s the whole plot.

And yet… it’s enough to start arguments at dinner, in ethics classrooms, in psychology labs, andbecause we can’t have nice thingsinside debates about

self-driving cars.

The trolley problem is a moral dilemma disguised as a simple question: Is it okay to harm one person to save five?

But it’s also a microscope. Move one tiny detailyour distance from the action, your intention, whether your hands are involvedand people’s moral

intuitions can flip like a pancake on a hot griddle. (A very ethical pancake. Probably.)

What Is the Trolley Problem, Really?

In its modern philosophical form, the trolley scenario is often traced to discussions that grew out of debates about the doctrine of double effect and

the difference between doing harm and allowing harm. The “classic” setup asks whether it’s morally permissible to

divert a trolley from a track where it will kill five people onto a track where it will kill one. The reason it’s sticky isn’t the math (five > one),

but the moral discomfort of becoming the person who decides that someone dies. [1] [9]

Then came the variations, and with them, the emotional whiplash. If you’re allowed to pull a lever, are you allowed to push a person off a footbridge to

stop the trolley? Most people who say “yes” to the lever say “absolutely not” to the shove, even though the body-count math looks the same. [2]

That gapbetween “I’ll flip a switch” and “I won’t push a person”is the trolley problem’s superpower. It exposes that moral reasoning is not only about

outcomes; it’s also about rules, rights, intentions, and the squishy human feelings we pretend aren’t running the meeting.

The Greatest Hits: Variations That Make Your Brain Loud

1) The Switch

You can divert the trolley. One person dies instead of five. Many people feel this is permissible, sometimes even obligatory, because it minimizes harm.

This tends to feel like ethical decision-making by spreadsheet: tragic, but “least bad.” [1]

2) The Footbridge

Now the lever is gone. You’re on a bridge above the track with a large person next to you. If you push them, they fall, the trolley stops, and five

people live. Most people recoil at this option, even if they previously endorsed saving five by sacrificing one. [2]

Philosophers and psychologists have proposed many reasons: direct physical force, treating a person as a means, the intention to kill, or simply that

pushing a stranger is emotionally horrifying in a way lever-pulling isn’t. (The lever feels like an “oops, physics,” while the shove feels like a

“hello, crime documentary.”)

3) Doing vs. Allowing (and Why It Matters)

A big theme underneath the trolley problem is whether there’s a moral difference between actively causing harm and passively letting harm happen.

Some approaches use the doctrine of double effect to argue that certain harms may be permissible as side effects but not as intended means. This is one

reason diverting a trolley can feel different from pushing someone into its path. [3]

4) Organ Transplant and Other “Please Don’t Make This a Policy” Variants

Another family of thought experiments swaps tracks for operating rooms: could a surgeon kill one healthy person and use their organs to save five patients?

Most people say noloudly. These cases highlight that “save more lives” isn’t the only moral value in play. Rights, duties, consent, and trust in social

systems matter because real life is not a vacuum-sealed logic puzzle. [1] [11]

Utilitarianism vs. Deontology: The Two-Party System of Moral Philosophy

The trolley problem is often used to introduce (and occasionally oversimplify) a classic ethical tension:

utilitarianism and deontological ethics.

Utilitarianism: “Maximize Well-Being”

Utilitarian reasoning evaluates actions largely by their consequencesoften summarized as maximizing overall good or minimizing overall suffering.

In trolley-style scenarios, that often points toward saving the greater number. It’s neat, mathematical, and emotionally suspicious (but still compelling),

which is why it keeps showing up in ethical decision-making conversations. [12]

Deontology: “Some Things Are Wrong Even If They ‘Work’”

Deontological ethics emphasizes duties, rules, and rights. Certain actionslike intentionally killing an innocent personmay be seen as impermissible even

if they produce better outcomes. This framework helps explain why many people draw a line at pushing the bystander in the footbridge case. [11]

Important note: most humans are “mixed-method” moral reasoners. We use a little consequence-thinking, a little rule-following, a little intuition, and a

little “what would my mom think if she saw this?” The trolley problem doesn’t prove one ethical theory is correct. It shows that our moral lives contain

multiple values that sometimes collide.

Why Your Brain Treats a Lever Like a Remote Control, But a Push Like a Horror Movie

Moral psychology stepped into the trolley problem like: “We’ll take it from here.” Researchers have used trolley-style dilemmas to study how people make

moral judgments and how emotion and cognition interact.

Emotion and the “Personal vs. Impersonal” Split

One influential line of work used brain imaging to explore how people respond to different moral dilemmas, distinguishing “personal” harms (like pushing

someone) from more “impersonal” actions (like flipping a switch). Findings suggested that emotionally engaging dilemmas can recruit different patterns of

brain activity than more abstract or indirect harms. [4]

You don’t have to be a neuroscientist to recognize the basic takeaway: moral judgment is not purely rational calculation. Your gut gets a vote, and it votes

early.

Intuition First, Reasoning Second

Another influential view in moral psychology argues that people often arrive at moral judgments quickly through intuition and then recruit reasoning to

justify those judgments afterwardlike a lawyer hired after the verdict. This doesn’t mean we never reason; it means a lot of “reasoning” is actually

explanation, persuasion, or post-hoc sense-making. [5]

Put bluntly: you’re not a cold-blooded ethics robot. You’re a story-telling primate with a conscience and an internet connection. The trolley problem

just makes that obvious.

Is the Trolley Problem “Realistic”? (And Why It Still Matters)

Critics sometimes dismiss the trolley problem as too artificial. Real moral life includes uncertainty, incomplete information, relationships, histories,

and consequences beyond body counts. True. But that’s also why thought experiments exist: they isolate a variable so we can see what we actually care about.

The trolley problem is less like a real emergency and more like a mental stress test.

In fact, researchers and educators keep returning to trolley dilemmas precisely because they reveal patterns:

intention vs. side effect, action vs. omission, direct force vs. indirect control,

and how quickly we switch between utilitarian and deontological instincts depending on framing. [3]

From Tracks to Tech: Self-Driving Cars and the Modern Trolley Problem

The trolley problem got a fresh set of wheels in conversations about autonomous vehicles. People asked: if a crash is unavoidable, should a car be

programmed to minimize casualties? Protect passengers? Follow rules no matter what? If you’re thinking, “This seems like an excellent way to start ten

lawsuits at once,” you’re not alone.

One famous project, MIT’s Moral Machine, invited people to make choices in stylized crash dilemmasessentially trolley problems with a steering wheel.

The platform was designed to gather public intuitions about how machines “should” behave. [7]

Related research using the Moral Machine reported tens of millions of decisions collected across many countries and territories, highlighting both broad

trends (people often prefer saving more lives) and deep disagreements (preferences can vary by culture, rule-following, age, and other factors). [8]

The headline lesson is not “we found the correct moral algorithm.” It’s “people disagree, and sometimes for uncomfortable reasons.”

Journalists and engineers have also noted a practical point: real-world safety work is often less about coding dramatic sacrifice scenarios and more about

preventing crashes in the first place. Still, the trolley framing forces public conversation about responsibility, transparency, and whose values get baked

into systems that affect lives. [10]

So… Can You Make the Impossible Choice?

Here’s the twist: the trolley problem is not a test you pass. It’s a mirror you look into.

Different answers can reflect different moral priorities:

- Consequences: minimize harm, save the most lives (a utilitarian pull).

- Rights and duties: don’t intentionally kill, don’t use people as tools (a deontological pull).

- Intentions: foresee harm vs. aim at harm (doctrine of double effect vibes).

- Character and care: what would a good person do; what do we owe each other beyond numbers?

The “impossible choice” feeling is the point. Moral dilemmas hurt because values can conflict. The trolley problem is a concentrated dose of that conflict,

delivered in a small, portable story you can carry into bigger questions: medical triage, public policy, corporate risk, personal trade-offs, and the ethics

of technology.

How to Discuss the Trolley Problem Without Turning Thanksgiving Into a Philosophy Cage Match

If you want the trolley problem to be more than a hot take generator, try these moves:

Ask “What principle are you using?”

Instead of debating the answer, identify the underlying value: consequences, rights, intentions, fairness, loyalty, rule-following, or care.

People often disagree less than it seemsthey’re optimizing for different moral goals.

Change one detail at a time

Variations are not “gotchas.” They help pinpoint which features matter to you. Is it physical contact? Intention? Consent? Proximity? The role you play?

Your answer to the trolley problem is really a set of answers to a set of questions.

Admit uncertainty

Real ethical decision-making includes doubt. If you’re 100% certain in every scenario, congratulations: you may be a vending machine, and you should seek

professional help (from an electrician).

Experiences: The Trolley Problem in Everyday Life (500+ Words)

Most of us will never stand beside a literal runaway trolley. But we run into trolley-shaped moments all the timesituations where every option has a cost,

and you’re choosing which cost you can live with. The stakes may be lower than life and death, but the psychology is familiar: responsibility, guilt,

uncertainty, and the fear of choosing wrong.

Picture a manager on a small team facing a budget cut. Keeping the project alive might mean laying off one person rather than letting the whole team dissolve.

The “utilitarian” move looks like saving five jobs by sacrificing onebut the human reality is that you’re not moving numbers on a whiteboard; you’re changing

someone’s rent payment, health insurance, and sense of security. That’s the trolley problem wearing a blazer and carrying a spreadsheet.

Or think about scheduling in a hospital or emergency setting. Sometimes resources are limited: time, staff, beds, attention. Decisions become triage-like:

who gets immediate help first, who can safely wait, and what happens if waiting turns out not to be safe. Even when the goal is “help the most people,”

the emotional weight doesn’t disappear. People want decisions to be fair, transparent, and humanenot just efficient. This is where moral frameworks collide:

outcomes matter, but so do dignity and duty.

At home, trolley problems can be smaller but strangely intense. You promised your kid you’d be at their performance, but your best friend calls with a crisis.

You can’t be in two places at once. Whose need is greater? Whose disappointment is more harmful? If you choose one, you are not just “allowing” the other

to happenyou’re participating in it, at least emotionally. The lever is your calendar. The tracks are your relationships.

Even consumer choices can feel trolley-ish. You can buy the cheaper product and keep your budget intact, or spend more on the option made under better labor

conditions (as far as you can tell) and sacrifice other needs. The dilemma isn’t theatrical, but it’s real: what do you owe strangers you’ll never meet?

How do you weigh competing responsibilities when information is incomplete?

And then there’s the modern digital version: social media platforms deciding which content to amplify, what to remove, and what to label. A policy that

reduces harm overall might still wrong individuals, misclassify content, or silence certain voices. Leaders describe these as “trade-offs,” but for users,

they can feel like being the person on the side trackselected by an invisible switch you didn’t know existed. [6]

The common thread in these everyday experiences is not that life is one big trolley problem; it’s that moral life often involves competing goods and

unavoidable losses. The trolley problem makes that structure impossible to ignore. It asks: when harm can’t be avoided, what principles guide you?

When you have power, what responsibilities come with it? And when you don’t have good options, how do you stay human while choosing among them?

Conclusion: The Point Isn’t the LeverIt’s You

The trolley problem endures because it’s deceptively simple and brutally revealing. It spotlights the tension between utilitarian calculations and

deontological rules, the pull of moral intuition, and the importance of intentions and agency. It also reminds us that ethics isn’t just about outcomesit’s

about what kind of world we’re building, what we owe one another, and how we handle responsibility when there’s no clean escape hatch.

Can you make the impossible choice? Maybe. But the better question is: what does your choice say you valueand are you willing to live by that

value when the “trolley” looks less like a thought experiment and more like your actual life?