Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What a Battery “Protection Chip” Actually Does

- So… Can a Battery Be “Turned Off”?

- How to Recognize a Protection-Chip Shutoff (Without Guessing Wildly)

- Safe Ways to “Get Power Back” When a Protection Circuit Trips

- Why Protection Chips Trip More Often Than You’d Expect

- Ship Mode, Storage Mode, and the “It’s New but It’s Dead” Mystery

- Design Note: Protection ICs vs. Full Battery Management Systems

- Safety Rules That Matter (Because Lithium Doesn’t Do “Oops”)

- Troubleshooting Scenarios (Specific Examples, No Sketchy Hacks)

- Experiences People Commonly Have With “Turned Off” Batteries (About )

- Conclusion: Let the Chip Do Its Job (And You Do Yours)

If you’ve ever had a device go from “working fine” to “I swear it was just at 42%” in one dramatic moment,

congratulations: you’ve met the battery’s protection chip. It’s the tiny bouncer inside many lithium-ion and lithium-polymer

batteries, deciding who gets power, when, and under what conditions. And yessometimes it “turns off” the battery output on purpose.

Here’s the good news: that shutoff is usually a safety feature, not a betrayal. Here’s the other news: if you try to defeat it,

you can turn a minor inconvenience into a major hazard. This guide explains what’s really happening, why protection chips cut you off,

and what safe steps can bring a battery back onlinewithout bypassing the very safeguards that keep lithium batteries from becoming

pocket-sized drama fires.

What a Battery “Protection Chip” Actually Does

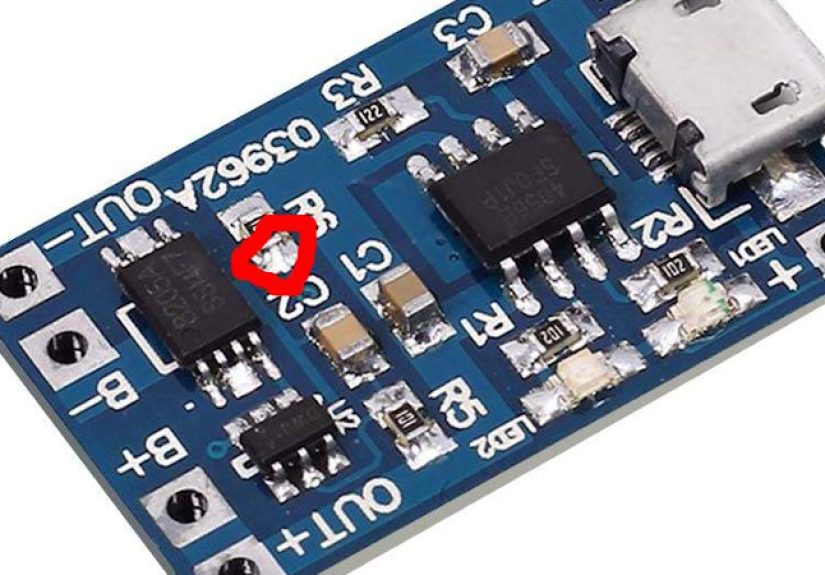

Many rechargeable packs include a protection circuit (often a small IC plus a couple of MOSFETs and supporting parts) designed to keep

the cell inside a safe operating window. In plain English: it watches voltage and current like a hawk, and if anything looks sketchy,

it disconnects the battery from the device and/or charger.

The core protections (the bouncer’s rulebook)

- Overcharge protection: Cuts off charging if voltage climbs too high.

- Overdischarge (deep discharge) protection: Cuts off the load if voltage drops too low.

- Overcurrent protection: Stops excessive current draw (like a motor stall or a sudden surge).

- Short-circuit protection: Reacts fast when current spikes hard and fast.

- Temperature protection (often pack-level): Uses sensors (like an NTC) so charging/discharging pauses when too hot or too cold.

In single-cell “protected” batteries (think protected 18650 cells or many small LiPo packs), the chip typically monitors the cell voltage

and senses current by measuring voltage across the MOSFETs or a small resistor. When limits are exceeded, it turns the MOSFET “switches”

offso your device sees… nothing. No power. No negotiation.

So… Can a Battery Be “Turned Off”?

Most standalone lithium cells don’t have an old-school on/off switch. But the protection circuit can effectively turn the output off

by opening the MOSFETs. To you, it looks exactly like the battery is dead, missing, or unplugged.

Common reasons the protection circuit shuts the party down

- Deep discharge lockout: A device sits in a drawer for months, drains too low, and the protection circuit disconnects the load.

- Overcurrent trip: Something pulls more current than the pack’s limit (jammed fan, stuck motor, failed component, or an oversized load).

- Short-circuit event: A damaged cable, moisture, debris, or a tool slip makes current spike instantly.

- Charging fault: Wrong charger, damaged port, or unstable power causes abnormal conditions.

- Temperature out of range: Cold garage in winter or a hot car in summer can push packs to pause charging/discharging.

- Shipping/storage (“ship”) mode: Some products intentionally disconnect the battery for long shelf life and ultra-low drain.

That last oneship modeis the most misunderstood. Many consumer devices arrive “dead” on purpose because the design isolates the battery

during storage. The first “wake” might happen when you plug it in, press a button, or follow the product’s intended activation flow.

How to Recognize a Protection-Chip Shutoff (Without Guessing Wildly)

A protection shutdown tends to have a few telltale patterns:

Signs you’re dealing with a protection cutoff

- The device won’t power on even though the battery was recently charged.

- Charging looks “weird” (blinking LEDs, rapid on/off, or refusing to start) but the charger itself works elsewhere.

- The battery percentage suddenly dives to 0% or the device reports “no battery” intermittently.

- It happens right after a heavy load (high-brightness flashlight mode, motor startup, heating element, or camera flash).

- The device works again after sitting on a charger for a whilethen behaves normally.

The protection circuit is doing its job: it’s protecting the cell from damage and reducing safety risk. Your job is to figure out

what triggered it and resolve thatnot to outsmart it with “one weird trick” that ends with melted plastic and regret.

Safe Ways to “Get Power Back” When a Protection Circuit Trips

Let’s be crystal clear: do not bypass, short, or “jump” lithium batteries to force them on. That’s risky even for experienced

technicians with the right equipment, and it’s especially unsafe for casual DIY. The safer path is to use the device’s intended charging

and recovery behavior.

Start with the simplest safe recovery steps

-

Use the correct charger and cable. If the device has a recommended adapter (voltage/current rating), use it.

Cheap cables can create voltage drops that look like faults. - Charge for 20–30 minutes before judging. Some packs won’t “wake” instantly, especially after deep discharge protection.

-

Bring it to room temperature. If it’s cold, let it warm naturally indoors; if it’s hot, let it cool.

Lithium charging is often limited outside a safe temperature window. - Check for obvious physical warning signs. Swelling, cracks, leaks, a chemical smell, or unusual heat are “stop immediately” signals.

- Inspect ports and contacts. Lint, corrosion, or bent pins can cause charging instability that triggers protection behavior.

When to stop troubleshooting and escalate

- If the battery is swollen, hot, leaking, or damaged: stop using it and follow safe disposal/recycling guidance.

- If the device repeatedly trips: the underlying issue may be the load (motor, board fault) rather than the battery.

- If it’s a sealed device under warranty: don’t pry it openmanufacturer service is the safer move.

- If it’s a power tool or e-bike pack: treat repeated cutoffs seriously; pack-level BMS events can indicate a failing cell group.

If a battery is frequently hitting protection limits, that’s not a “battery personality problem.” It’s data. Something about the way it’s being charged,

stored, or used is pushing it out of boundsoften heat, age, damage, or a demanding load profile.

Why Protection Chips Trip More Often Than You’d Expect

Protection circuits are conservative by design. They’re built to prevent worst-case outcomes, so they’d rather annoy you than allow deep discharge or a

high-current event to keep going.

Three common triggers in real devices

-

Voltage sag under load: Older cells have higher internal resistance. A high-drain moment (like a motor start) can make voltage dip

below the cutoff threshold even if the battery “seems” half full. -

Accessory chaos: Off-brand chargers, long cables, and worn connectors can create unstable input power, confusing charging logic and

contributing to repeated cutoffs. -

Storage drain: Even “off” devices draw tiny currents. Over weeks or months, a battery can cross the deep discharge threshold and be

disconnected by protection circuitry.

Engineers often add intentional “storage” or “ship” behaviors to avoid exactly that last problem. Some designs disconnect the battery so thoroughly that the

shelf-life drain becomes almost negligiblegreat for warehouses, less great for impatient unboxing.

Ship Mode, Storage Mode, and the “It’s New but It’s Dead” Mystery

Ship mode is basically a battery-saving nap. In many designs, a load switch or power path arrangement physically disconnects the battery from the system,

reducing quiescent current and making it more likely the device survives months in a box and still wakes up on day one.

What ship mode looks like to a normal human

- You open the box and the device won’t turn on.

- Plugging it in suddenly makes it come alive.

- Sometimes a long press or specific “wake” button is involved.

If you’re designing products (or just curious), ship mode can be implemented with dedicated power-management parts and control signals so the battery

disconnect is intentional, reversible, and saferather than “accidentally dead in storage.”

Design Note: Protection ICs vs. Full Battery Management Systems

People say “protection chip” and mean a lot of different things. A small single-cell protection IC is common in consumer LiPo packs.

A BMS in larger packs (power tools, e-bikes, EV modules) can include monitoring, balancing, temperature management, communications,

and more complex fault logic.

Why bigger packs get bigger brains

- Cell imbalance: multi-cell strings drift over time; balancing helps keep the pack usable and safer.

- Higher energy: more stored energy increases the consequences of faults.

- More sensors: temperature points, current sensing, sometimes isolation monitoring.

- Standards and testing: many products must meet safety standards that evaluate fault behavior.

Either way, the theme is the same: protection exists because lithium batteries are incredible at delivering energyand spectacularly bad at forgiving

abuse, damage, or incorrect charging.

Safety Rules That Matter (Because Lithium Doesn’t Do “Oops”)

You don’t need to be paranoid. You do need to be consistent.

Smart habits that reduce trips and reduce risk

- Buy certified, reputable products (especially chargers and power banks). Off-brand power gear is a frequent troublemaker.

- Don’t charge on soft surfaces (beds, couches) and don’t cover charging devicesheat management matters.

- Stop using damaged batteries immediately. Swelling or heat is not “character,” it’s a warning.

- Store batteries cool and dry, and avoid leaving them at 0% for long periods.

- Recycle properly. Don’t toss lithium batteries in household trash.

If you want fewer annoying shutdowns, aim for kinder operating conditions: less heat, better charging gear, and avoiding deep discharge storage.

The protection chip will still do its jobbut it’ll have fewer reasons to slam the door.

Troubleshooting Scenarios (Specific Examples, No Sketchy Hacks)

1) The flashlight that “dies” on turbo mode

High-output flashlights can pull big current spikes. An older protected cell may sag in voltage and trip undervoltage or overcurrent protection.

Fix: use the manufacturer-recommended battery type, keep cells in good condition, and avoid sustained turbo if the hardware isn’t designed for it.

2) The power bank that refuses to charge

If the power bank has been drained hard or stored for a long time, it may enter a protective state. Fix: use a quality charger, give it time,

and if it heats up or swells, stop using it and recycle it. Also check for recallspower banks have had notable safety recalls.

3) The e-bike or tool pack that cuts out under load

Pack-level BMS cutoffs under acceleration or high torque can mean the pack is protecting itself from overcurrent or undervoltage sag.

Fix: reduce load spikes (where possible), avoid extreme temperatures, and get the pack evaluated if it’s recurringespecially if the pack is aging.

Experiences People Commonly Have With “Turned Off” Batteries (About )

The most common “experience” sounds like a conspiracy: “My battery was fine, then it hit 0% instantly, and now it won’t charge.”

What’s usually happening is less dramatic and more… physics. A battery that has aged or been stored too long can develop higher internal resistance,

meaning it can’t deliver high current without its voltage dropping sharply. When the voltage dips below the protection threshold, the circuit disconnects

the output, and the device interprets that as “battery empty” or “battery missing.” It feels sudden because the cutoff is suddenlike a light switch.

Another classic: “It was in my drawer for months, now it’s dead-dead.” Devices often draw tiny standby current even when “off,” and batteries naturally

self-discharge over time. If the pack crosses the deep-discharge cutoff, the protection circuit stops the load from pulling it even lower. The experience

is frustrating because the device won’t wake up immediately. But in many cases, the pack can recover safely by being charged with the intended charger and

given a little timebecause the goal is to bring the cell back into a normal voltage range without stressing it.

People also run into “false alarms” caused by accessories. A bargain cable with thin conductors can create enough voltage drop that charging becomes unstable.

The charger and device keep renegotiating power, the battery management logic sees inconsistent input, and the user experiences it as “it keeps cutting in and out.”

Swap in a reputable cable and adapter, and suddenly the battery stops acting like it’s possessed. The protection circuit wasn’t wrongit was reacting to a messy situation.

Temperature is another sneaky one. Someone tries to charge in a cold garage and says, “My battery turned off.”

Many lithium systems limit charging when it’s too cold (or too hot) because plating, heat buildup, and other side effects can increase risk and damage.

The user experience looks like refusal: no charge, slow charge, or a device that won’t power under load. Bring the device to a comfortable indoor temperature,

and the “mystery” often resolves itself.

Finally, there’s the “I thought it was just a little dent” story. A battery that’s been dropped, crushed, punctured, or swollen may still appear to work

until it doesn’t. Protection circuits can trip more often as a pack becomes unstable, but physical damage is a line you don’t want to cross.

People who stop using a damaged battery early usually end up with a boring ending (the best kind). People who keep charging a swollen pack often end up with

a much more exciting story than they wanted. If a pack looks wrong, feels unusually hot, smells odd, or behaves unpredictably, the safest “experience” is:

stop, isolate, and recycle through the proper channels.

Conclusion: Let the Chip Do Its Job (And You Do Yours)

Turning a battery “off” with a protection chip isn’t a gimmickit’s a safety and longevity feature. When output is cut off, it’s typically because the pack

detected a condition that could damage the cell or raise risk: too low, too high, too much current, too much heat, or sometimes just “we’re in ship mode.”

The best fix is rarely clever. It’s usually practical: correct charging gear, sane temperatures, avoiding deep storage at 0%, and retiring batteries that show

warning signs. Treat the protection circuit like a smoke detector: you can silence it safely by removing the problem, not by ripping it off the ceiling.