Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- How Cold Is Webb, Exactly?

- Why a Space Telescope Needs to Be Freezing

- The Engineering Magic That Keeps Webb So Cold

- What a Super-Cold Telescope Can Actually Do

- How Webb Compares to the Coldest Places in the Universe

- Lessons From Building One of the Coldest Objects in Space

- Living With a Telescope That’s Colder Than Deep Space: Human Experiences

Imagine building a $10 billion telescope, launching it a million miles from Earth, and then cheering

when it starts to vanish from the infrared universe because it’s finally cold enough.

That’s essentially what happened with NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Thanks to a giant space sunshield and a high-tech cryocooler, Webb has become one of the coldest

engineered objects in the cosmos colder than any place on Earth, and only a few dozen degrees

above absolute zero.

This extreme chill isn’t a quirky design choice. Webb is an infrared observatory, built to sense

the faint heat signatures of distant galaxies, newborn stars, cold exoplanets, and even icy dust

clouds that are just starting to assemble into planetary systems. To see those whisper-faint signals,

Webb has to make sure it isn’t glowing in infrared itself which means cooling its mirrors and

instruments to astonishingly low temperatures.

So how cold is “one of the coldest objects in space,” why does it matter, and what can a telescope

this frigid actually do? Let’s bundle up and take a tour.

How Cold Is Webb, Exactly?

First, a quick temperature translation. Scientists often use Kelvin (K), a scale

that starts at absolute zero the point where all atomic motion would stop,

at 0 K (–273.15°C or –459.67°F).

-

Webb’s main optics and three of its four instruments cool down passively to around

37–40 K (about –389°F / –233°C). -

Its coolest instrument, the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), is actively chilled

with a cryocooler to about 7 K (around –447°F / –266°C), just a few degrees

above absolute zero.

For comparison, the coldest naturally occurring places on Earth such as Antarctica’s Vostok

Station or high ridges on the East Antarctic Plateau have hit lows around –130°F (–90°C).

Webb’s coldest hardware is more than 300 degrees Fahrenheit colder than that.

If Earth’s record-breaking cold snaps are like a chest freezer, Webb is more like a laboratory

cryostat turned up to “are you serious?”

And while the background of the universe (the cosmic microwave background) sits at about 2.7 K,

the fact that Webb is a large, complex, powered spacecraft makes holding part of it at 7 K an

extraordinary engineering achievement.

Why a Space Telescope Needs to Be Freezing

Webb is designed to see the universe in infrared light.

Many of the most interesting things in space baby stars embedded in dust, distant galaxies whose

light is stretched by cosmic expansion, cool exoplanets, icy molecules in dark clouds all shine

mainly in the infrared.

Here’s the catch: anything that has a temperature above absolute zero gives off some infrared

radiation. That includes not just stars and planets, but the telescope itself.

If Webb were warm, it would swamp its own detectors with heat “noise,” like trying to see a

candle in front of a searchlight.

Seeing the First Galaxies and Hidden Stars

By going extremely cold, Webb’s detectors can pick out:

-

Ultra-distant galaxies, whose light has been traveling for over 13 billion years

and is stretched into the infrared by the expansion of the universe. -

Stars still wrapped in dusty cocoons, which are invisible or dim in visible light

but glow in infrared. - Cold planetary disks, where dust and ice are just beginning to clump into planets.

-

Cool exoplanets and brown dwarfs, whose temperatures are closer to that of a

pizza oven than a star.

In short, the colder Webb is, the less it interferes with the light it’s trying to capture.

The telescope effectively “steps out of its own way” so the universe can shine through.

The Engineering Magic That Keeps Webb So Cold

Keeping a multitonne, power-hungry observatory this cold is not as simple as “open a window and

let space in.” Webb uses a combination of clever orbit choices, giant shields, and precision

cooling hardware to reach and maintain its icy state.

Parking Webb in the Shade: The L2 Orbit

Webb orbits near the Sun–Earth L2 Lagrange point, about one million miles

(1.5 million kilometers) from Earth on the night side of the planet. From this vantage point:

- The Sun, Earth, and Moon are all roughly in the same direction.

- The telescope can keep those bright, warm bodies behind a shield at all times.

- Webb has a stable thermal environment, which is crucial for precision observations.

L2 isn’t a physical object, but more like a gravitational “sweet spot” where Webb can orbit the Sun

in step with Earth while always facing away from our star and toward deep space.

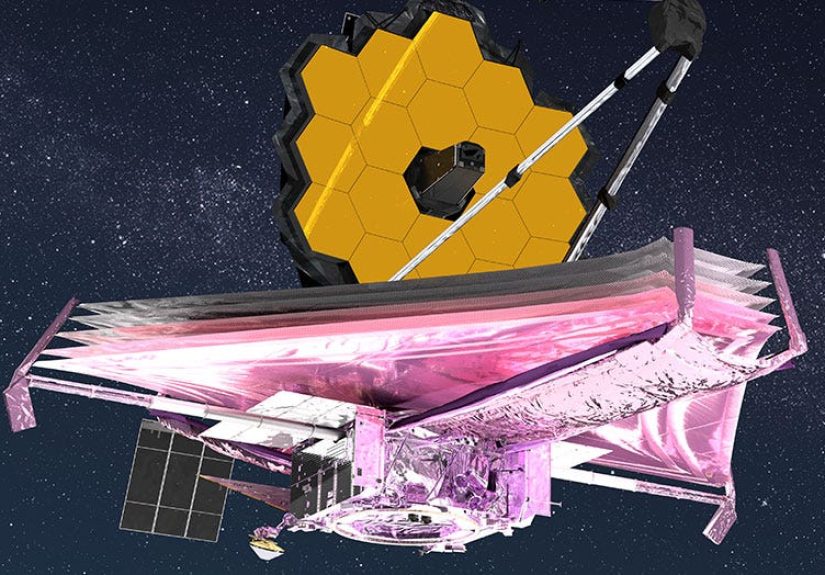

The Tennis-Court Sunshield

The most visually striking part of Webb (aside from that golden mirror) is its

kite-shaped sunshield, roughly the size of a tennis court and consisting of

five ultra-thin layers of Kapton coated with reflective metal.

The hot side of the shield, facing the Sun, Earth, and Moon, can be as hot as a summer sidewalk.

But by the time heat filters through all five layers, the cold side facing the telescope is more

than 300°C cooler. That temperature drop allows the mirrors and most instruments

to passively cool down to around 40 K simply by radiating their heat into deep space.

Each layer is slightly smaller than the one below it, which helps heat radiate out the sides without

creeping toward the telescope. The design is so sensitive that even tiny tears or wrinkles had to be

carefully controlled during testing and deployment.

MIRI: The Coolest Instrument of All

While most of Webb can chill out with passive cooling, MIRI the Mid-Infrared

Instrument needs to go even colder to do its job. MIRI operates in longer infrared wavelengths,

which are particularly sensitive to thermal noise. To reach its operating temperature of about

7 K, MIRI uses a sophisticated helium-based cryocooler.

This cryocooler is like a refrigerator stretched across a spacecraft. Compressors and heat exchangers

on the “warm” spacecraft bus send chilled helium gas through long lines to MIRI’s hardware on the cold

instrument module. The gas expands, gets even colder, and absorbs heat from the instrument, which is

then carried away and radiated into space.

Unlike old-school observatories that carried tanks of cryogenic liquids that eventually boil away,

Webb’s cryocooler is a closed-loop system. It can keep MIRI cold for many years

without refilling a crucial feature for a telescope that can never be serviced in person.

What a Super-Cold Telescope Can Actually Do

Being one of the coldest objects in space is impressive, but Webb wasn’t chilled just to win some

cosmic record. The real payoff is in the science.

Probing the First Billion Years of the Universe

Webb has already spotted galaxies whose light comes from the universe’s first few hundred million

years after the Big Bang. These objects are incredibly faint and redshifted their light has been

stretched into longer, redder wavelengths over billions of years of cosmic expansion. A warm telescope

would simply never see them; its own glow would drown them out.

By keeping its optics and detectors icy, Webb can stack long exposures and tease out these ancient,

nearly invisible signals, helping astronomers understand how the first galaxies formed, grew, and

merged into the cosmic structures we see today.

Studying Cold Exoplanets and “Failed Stars”

Webb’s mid-infrared sensitivity also makes it a powerful tool for studying cold exoplanets and

brown dwarfs (objects heavier than planets but too small to ignite as true stars).

Observations in mid-infrared wavelengths allow scientists to:

- Measure the temperature of cold, Jupiter-like planets.

- Analyze atmospheric molecules like water vapor, methane, and carbon dioxide.

- Explore the weather patterns and cloud structures on these distant worlds.

Many of these targets are only slightly warmer than the telescope itself, which again underscores why

Webb’s own temperature has to be extremely stable and incredibly low.

Mapping the Coldest Ice and Dust in Space

Webb has also been used to detect icy molecules in dark, dense clouds where stars

and planets are just beginning to form. These regions can be colder than –430°F (–260°C), and the

ices there water, carbon dioxide, methane, ammonia, and more are the raw ingredients of future

planets and potentially life-supporting environments.

By measuring how starlight is absorbed by these ices, Webb can map their composition and distribution,

helping researchers understand how complex molecules form long before planets or oceans appear.

How Webb Compares to the Coldest Places in the Universe

Webb is one of the coldest engineered objects in space, but how does it stack up against

nature’s own deep-freeze champions?

- On Earth: The coldest spots in Antarctica bottom out near –130°F (–90°C).

-

In the solar system: Shadowed craters on the Moon and Mercury can reach below

–400°F (~30 K), and the outer planets and their moons see similarly frigid temperatures. -

In deep space: The cosmic microwave background sets a baseline of 2.7 K, and

certain rare nebulae can plunge close to 1 K.

Webb doesn’t beat the coldest natural regions in raw temperature, but it’s incredibly cold for a large,

active machine bristling with electronics, moving parts in its cryocooler, and high-precision optics

pointing with jaw-dropping accuracy. It’s like parking a running supercomputer in a walk-in freezer

and then dialing the thermostat down another 400 degrees.

Lessons From Building One of the Coldest Objects in Space

Achieving and maintaining these temperatures has taught engineers and scientists a lot about how to

design future missions.

-

Thermal control must be part of the mission from day one. Webb’s sunshield,

orbit, and instrument layout were all designed around temperature requirements, not added later

as a patch. -

Passive and active cooling work best together. Passive cooling gets most of the

telescope down to very low temperatures without consuming much power, while active cooling pushes

the most sensitive components that final step toward absolute zero. -

Reliability is everything. Webb can’t be repaired, so its cryocooler and thermal

systems had to be tested extensively on the ground. The payoff is a telescope that can operate

for many years, delivering science long after its commissioning phase.

Future observatories that probe even longer wavelengths or attempt even more sensitive measurements

will borrow heavily from Webb’s thermal playbook.

Living With a Telescope That’s Colder Than Deep Space: Human Experiences

While Webb’s hardware may be chilling quietly in the vacuum of space, the experience for the people

who built and operate it has been anything but cold.

The Emotional Roller Coaster of Cooldown

After launch, engineers watched Webb cool down step by step over weeks and months. Every few days,

graphs from temperature sensors would tick lower as the sunshield unfurled, radiators kicked in,

and the observatory slowly slipped into its deep-space comfort zone.

For the team, each milestone was both nerve-wracking and exhilarating:

-

Seeing the primary mirror segments drop toward their target temperatures meant the sunshield

was working. - Watching the detectors cool to the mid-30 K range signaled that passive cooling was doing its job.

-

The moment MIRI crossed below 10 K as the cryocooler ramped up was a major emotional high point

proof that one of Webb’s most complex systems was ready to deliver.

In interviews, engineers have described these phases as a mix of “holding your breath” and “Christmas

morning for months in a row.” Each new temperature plateau wasn’t just a number; it was a checkmark

for decades of design work.

Operating an Ultra-Cold Telescope From a Warm Control Room

Day-to-day, Webb’s operations team works in shirtsleeves at mission centers on Earth while monitoring

a telescope that could make liquid nitrogen look balmy. Their tools include dashboards full of

telemetry temperatures, voltages, pointing data that show how the observatory is behaving in

real time.

If MIRI’s temperature ticks up even a fraction of a degree, that’s a big deal. Schedules can be

adjusted, different observation modes might be chosen, and the team may tweak how the cryocooler

cycles to keep things stable. Stability is just as important as raw cold: tiny temperature swings

can affect focus, detector performance, and calibration.

For scientists planning observations, understanding Webb’s thermal behavior has become part of their

job. Proposals for observing time now routinely consider:

- How long an exposure can run before thermal drift becomes an issue.

- Whether a sequence of observations might gently warm part of the telescope.

-

Which combinations of instruments place the least thermal stress on the observatory while still

delivering the needed data.

It’s a subtle dance between science goals and the realities of running a giant frozen observatory

millions of miles away.

How the Public Experiences Webb’s Cold

Most of us will never look at a temperature plot from Webb, but we do experience the benefits of

its extreme cold through the images and data it sends back. Those now-iconic pictures of glittering

galaxy clusters, star-forming nurseries, and eerie exoplanet atmospheres are only possible because

the telescope is dark and quiet in infrared.

When you see a Webb image full of delicate wisps of dust, sharp points of starlight, and subtle

structures in galaxies, you’re indirectly seeing the telescope’s temperature control in action.

The faintest features in those images might represent just a whisper of energy the kind that

would disappear entirely if Webb were even a little bit warmer.

In that sense, the “coldness” of Webb isn’t something you feel on your skin; it’s something you

see with your eyes and understand with your brain. The silence of its thermal design lets the

universe speak more clearly.

What Webb’s Cold Future Might Look Like

Over time, Webb will warm and cool slightly as it ages, its orbit evolves, and its systems shift.

But its fundamental status as one of the coldest engineered objects in space will remain central

to its mission. Each new discovery from the chemistry of exoplanet atmospheres to the structure

of the earliest galaxies will trace back, in part, to that giant sunshield and that hard-working

cryocooler silently doing their jobs.

For the next generation of space telescopes, Webb is more than a pathfinder for science; it’s a

blueprint for how to keep complex machines colder than anything we can experience on Earth. And for

the rest of us, it’s a reminder that sometimes, to see the hottest, brightest moments in cosmic

history, you first have to build something that’s unbelievably, gloriously cold.